Nói về Đất Nước, Con Người và Lịch Sử Nước Mã Lai Á

The nature of Malaysia as a modern state.

https://youtu.be/-QF98vjDo2o

Sự Ngu Ngốc của Người Tàu xứ Mã Lai Á

How foolish of the Chinese Malaysian?

https://youtu.be/VLTG7pRVskE

Why does a Malaysian Chinese feel sick of China?

https://youtu.be/45PS48c7E7M

What had I been shocked in China?

https://youtu.be/22lzsNp37BQ

Will the world boycott China? Will I be involved innocently?

https://youtu.be/8rwVTIJ8EU4

why I am afraid I would be involved innocently because the image of Chinese people is becoming bad, and I will point out that the Chinese people do not know that how is thier image in the people's eyes, and for them, it is not easy to make it better, and the Chinese strategy of one belt one road will make hurt to its own people too. Hope that my content is interesting and informative to you guys, thank you!

Tại sao ông Lý Quang Diệu buộc người Singapore học Tiếng Hoa?

https://youtu.be/1yuqITgeVg8

Người Hoa ở Đông Nam Á có gì khác biệt với người Trung Quốc?

https://youtu.be/F8NMwGXluCw

....................................................

|

Người Việt ghi nhớ: Người Việt nên biết rõ và học kỹ về đất nước và dân tộc người Mã Lai Á. Người Mã Lai Á và đất nước họ không giống như những thập niên trước. Trước kia, Mã Lai là một đất nước phẳng lặng, không nổi bậc, không sôi động, luôn bận với việc diệt mầm mống Mao cộng sản, bây giờ họ đã thoát nạn cộng sản, và trở thành nước dân chủ và tự do, đất nước Mã Lai rất khác hơn xưa.

Việt Nam đã gia nhập vào khối Asian, ít nhiều cũng phải trực tiếp có giao thương. Chúng ta phải tự hỏi: Tại sao xưa kia vua chúa ta chỉ tiếp nhận văn hóa của người Chàm nhưng không phổ biến gì mấy về tôn giáo Chàm là đạo Hồi? Đạo Hồi rất tương phản với năm (5) tôn giáo chính ở Việt Nam: • Phật giáo, • Thiên Chúa giáo, và Tin Lành • Hòa Hảo giáo, • Cao Đài Giáo, • Thờ cúng Ông Bà, Tổ Tiên (Việt Đạo) Nếu người Việt không khéo léo, tế nhị và lịch sự trong phép xử thế, chúng ta sẽ mất tình giao hảo với nước láng giềng Má Lai Á đang trở thành mạnh lên, giàu lên, và đông dân lên... với những giếng dầu được trời hay thiên nhiên ưu đãi họ, cộng với kỹ thuật cao và rất tân tiến của đất nước này. Chúng ta phải nhanh nhẹn bắt kịp đà tân tiến, nước chúng ta nay là cộng sản (quốc tế cộng sản), nên bị quốc tế cộng sản kềm kẹp vào khuôn khổ lý thuyết cộng sản, tư tưởng cộng sản. Nước Tàu là nước cộng sản, nhưng thế giới tự do rất sợ nước Tàu, người Tàu vì họ vì những lý do sau đây: 1. Đất đai quá rộng lớn, 2. Người đông nhất thế giới, 3. Độc tài, không tuân thủ luật lệ thế giới, họ chế tạo vi trùng sinh học như bệnh Sar virus (2006), Corona virus (2020)... Hãy học lại bài học lịch sử mà vua chúa, bậc tiền bối đã xử thế. Mà ngày xưa chúng ta đâu đã có khối Asian đâu, nay phải gia nhập, ta cần phải lưu ý kỹ và nhiều thêm nữa. |

.............................

Lịch sử Malaysia

Bách khoa toàn thư mở Wikipedia

Lịch sử Malaysia

> Các vương quốc đầu tiên

Xích Thổ (100 TCN–TK7)

Gangga Negara (TK2–TK11)

Langkasuka (TK2 - TK7)

Bàn Bàn (TK3 – TK6)

Vương quốc Kedah (630-1136)

Srivijaya (TK7 - TK14)

Thời kỳ Hồi giáo ảnh hưởng

Hồi quốc Kedah (1136–TK19)

Hồi quốc Melaka (1402–1511)

Hồi quốc Sulu (1450–1899)

Hồi quốc Kedah (1528–TK19)

> Thuộc địa của Châu Âu

Malacca thuộc Bồ Đào Nha (1511-1641)

Malaysia thuộc Anh (1641-1946)

Vương quốc Sarawak (1841–1946)

Bắc đảo Borneo trong liên bang Bắc đảo Borneo (1882–1963)

> Malaysia trong thế chiến thứ nhì

Nhật Bản xâm chiếm (1941–1945)

Tiến tới thống nhất và độc lập

Liên hiệp Mã Lai (1946–1948)

Liên bang Mã Lai (1948–1963)

. Độc lập (1957)

Liên bang Malaysia (1963–hiện nay)

Hồi giáo qua Malaysia ngay từ thế kỷ 10, song đến thế kỷ 14 và 15 thì tôn giáo này mới lần đầu thiết lập nền tảng trên bán đảo Mã Lai. Việc tiếp nhận Hồi giáo kéo theo sự xuất hiện của những vương quốc Hồi giáo, nổi bật nhất trong số đó là Malacca. Văn hóa Hồi giáo có ảnh hưởng sâu sắc đối với người Mã Lai.

Bồ Đào Nha là cường quốc thực dân châu Âu đầu tiên thiết lập căn cứ tại Malaysia, chiếm Malacca năm 1511, tiếp theo họ là người Hà Lan.

Anh Quốc ban đầu thiết lập các căn cứ tại Jesselton, Kuching, Penang, và Singapore, cuối cùng bảo đảm được quyền bá chủ của mình tại lãnh thổ nay là Malaysia.

Hiệp định Anh-Hà Lan năm 1824 xác định ranh giới giữa Malaya thuộc Anh và Đông Ấn Hà Lan.

Giai đoạn thứ tư của quá trình tiếp nhận ảnh hưởng ngoại quốc là sự nhập cư của những công nhân người Hoa và người Ấn nhằm đáp ứng nhu cầu của kinh tế thuộc địa do Anh Quốc thiết lập trên bán đảo Mã Lai và Borneo.[1]

Trong Chiến tranh thế giới thứ Nhì, Nhật Bản xâm chiếm Malaysia, chấm dứt quyền thống trị của Anh Quốc. Chủ nghĩa dân tộc được giải phóng trong thời gian Nhật Bản chiếm đóng Malaya, Bắc Borneo và Sarawak từ 1942 đến 1945.

Tại Malaysia bán đảo, Đảng Cộng sản Malaya tiến hành nổi dậy vũ trang chống Anh Quốc, song bị dập tắt bằng quân sự. Sau đó, Liên bang Malaya độc lập đa dân tộc được thành lập vào năm 1957.

Đến ngày 31 tháng 8 năm 1963, các lãnh thổ của Anh Quốc tại miền bắc đảo Borneo và Singapore được trao quyền độc lập và cùng các bang trên Bán đảo lập nên Malaysia vào ngày 16 tháng 9 năm 1963.

Hai năm sau, Quốc hội Malaysia tách Singapore khỏi liên bang.[2] Đầu thập niên 1960, Malaysia và Indonesia xảy ra đối đầu. Bạo loạn dân tộc trong năm 1969 dẫn đến áp đặt luật tình trạng khẩn cấp, cắt giảm sinh hoạt chính trị và tự do dân sự. Kể từ 1970, "liên Minh Mặt Trận Dân Tộc" do Tổ chức dân tộc Mã Lai thống nhất (UMNO) lãnh đạo là phe phái chính trị cầm quyền tại Malaysia.

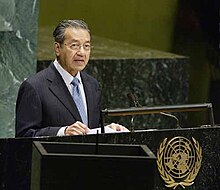

Dưới thời Mahathir Mohamad, Malaysia trải qua tăng trưởng kinh tế từ thập niên 1980.

Vào thời điểm Mahathir chuẩn bị rời chính trường, Malaysia từ một nước nông nghiệp đã trở thành một nền kinh tế hiện đại, đa dạng. Mahathir đã để lại dấu ấn không thể phai mờ trong lịch sử phát triển Malaysia.

Tiền sử

Tại Lenggong, khai quật được những chiếc rìu tay bằng đá của giống người ban đầu mà có thể là Homo erectus. Chúng có niên đại 1,83 triệu năm, là bằng chứng sớm nhất về việc họ Người cư trú tại Đông Nam Á.[3] Bằng chứng sớm nhất về sự cư trú của người hiện đại tại Malaysia là sọ người 4.000 năm tuổi khai quật từ hang Niah tại Borneo vào năm 1958.[4]

Bộ xương hoàn chỉnh cổ nhất phát hiện được tại Malaysia là người Perak 11.000 năm tuổi khai quật vào năm 1991.[5]

Những nhóm người bản địa trên bán đảo có thể phân thành ba dân tộc, Negrito, Senoi, và Mã Lai nguyên thủy.[6]

Những dân cư đầu tiên của bán đảo Mã Lai hầu như chắc chắn là người Negrito.[7] Những người săn bắn thuộc Thời đại đồ đá giữa này hầu như chắc chắn là tổ tiên của Semang, một dân tộc Negrito có lịch sử lâu dài tại bán đảo Mã Lai.[8]

Người Senoi xuất hiện như một nhóm hỗn hợp, với khoảng một nửa DNA ti thể mẫu hệ truy nguyên tới tổ tiên của người Semang và khoảng một nửa là người di trú đến từ Đông Dương sau đó. Các học giả đưa ra giả thuyết rằng họ là hậu duệ của những dân cư nông nghiệp nói tiếng Nam Á ban đầu, họ đem ngôn ngữ và kỹ thuật của mình đến phần phía nam của bán đảo vào khoảng 4.000 năm trước. Họ liên hiệp và hiệp nhất với dân cư bản địa.[9]

Những người Mã Lai nguyên thủy có nguồn gốc đa dạng hơn[10] và đã định cư tại Malaysia vào khoảng 1000 TCN.[11]

Mặc dù họ thể hiện một số liên kết với những dân cư khác tại Đông Nam Á Hàng Hải, song một số cũng có tổ tiên tại Đông Dương vào khoảng kỳ băng hà cực độ cuối khoảng 20.000 năm trước. Những nhà nhân loại học ủng hộ quan điểm rằng người Mã Lai nguyên thủy có nguồn gốc từ nơi mà nay là Vân Nam, Trung Quốc.[12] Tiếp theo đó là một sự phân tán vào đầu thế Toàn Tân qua bán đảo Mã Lai đến quần đảo Mã Lai.[13]

Khoảng 300 TCN, họ bị người Mã Lai thứ đẩy và nội lục, người Mã Lai thứ là một dân tộc thời đại đồ sắt hoặc đồ đồng và có nguồn gốc một phần từ người Chăm.

Người Mã Lai thứ là dân tộc đầu tiên trên bán đảo sử dụng các công cụ bằng kim loại, là tổ tiên trực tiếp của người Mã Lai Malaysia hiện nay, họ mang theo các kỹ thuật canh tác tiến bộ.[8]

Các vương quốc đầu tiên

Trong thiên niên kỷ đầu tiên Công Nguyên, người Mã Lai trở thành dân tộc chiếm ưu thế trên bán đảo. Một số tiểu quốc ban đầu hình thành và chịu ảnh hưởng lớn từ văn hóa Ấn Độ.[14] Ảnh hưởng của Ấn Độ trong khu vực truy nguyên ít nhất là đến thế kỷ 3 CN. Văn hóa Nam Ấn được truyền bá đến Đông Nam Á nhờ vương triều Pallava trong thế kỷ 4 và 5.[15]

Người Tamil cổ đại gọi bán đảo Mã Lai là Suvarnadvipa hay "bán đảo hoàng kim". Bán đảo được thể hiện trong bản đổ của Ptolemaeus với tên "bán đảo hoàng kim", ông thể hiện eo biển Malacca với tên Sinus Sabaricus.[16] Quan hệ mậu dịch với Trung Hoa và Ấn Độ được thiết lập trong thế kỷ 1 TCN.[11] Những mảnh vỡ đồ gốm Trung Hoa phát hiện được tại Borneo có niên đại từ thế kỷ 1 sau khi nhà Hán khuếch trương về phía nam.[17]

Trong những thế kỷ đầu tiên của thiên niên kỷ thứ nhất, dân cư tại bán đảo Mã Lai tiếp nhận các tôn giáo Ấn Độ là Ấn Độ giáo và Phật giáo, chúng có tác động lớn về ngôn ngữ và văn hóa của dân cư tại Malaysia.[18] Hệ thống chữ viết tiếng Phạn được sử dụng ngay từ thế kỷ 4.[19]

Một số vương quốc Mã Lai tồn tại trong thế kỷ 2 và 3, số lượng đến 30, chủ yếu tập trung tại bờ phía đông của bán đảo Mã Lai.[14] Trong số những vương quốc đầu tiên được biết đến có cơ sở tại khu vực nay là Malaysia, có quốc gia cổ Langkasuka nằm tại miền bắc bán đảo Mã Lai và có căn cứ tại lãnh thổ Kedah ngày nay.[14]

Quốc gia này có liên kết mật thiết với Phù Nam vốn cũng cai trị bộ phận miền bắc Malaysia cho đến thế kỷ 6.

Theo Sejarah Melayu ("Biên niên sử Mã Lai"), hoàng tử Phù Nam Raja Ganji Sarjuna thành lập vương quốc Gangga Negara (tại Beruas, Perak ngày nay) trong thập niên 700. Các biên niên sử Trung Hoa trong thế kỷ 5 nói về một cảng lớn ở phương nam gọi là Can Đà Li (干陁利), được cho là nằm bên eo biển Malacca.

Trong thế kỷ 7, biên niên sử Trung Hoa đề cập đến Thất Lợi Phật Thệ, và nó được cho là ám chỉ Srivijaya.

Từ thế kỷ 7 đến thế kỷ 13, phần lớn bán đảo Mã Lai nằm dưới quyền cai trị của Đế quốc Srivijaya theo Phật giáo. Địa điểm trung tâm của Srivijaya được cho là tại một cửa sông tại miền đông đảo Sumatra, đặt cơ sở gần Palembang hiện nay.[20]

Trong hơn sáu thế kỷ, các Maharajah của Srivijaya cai trị một đế quốc hàng hải là đại cường quốc trong khu vực. Đế quốc dựa vào mậu dịch, với các vương tại địa phương (dhatu hay thủ lĩnh cộng đồng) tuyên thệ trung thành với quân chủ trung ương nhằm cùng hưởng lợi.[21]

Tượng Quán Thế Âm phát hiện được tại Perak, thế kỷ 8–9

Quan hệ giữa Srivijaya và Đế quốc Chola tại Nam Ấn là hữu hảo trong thời kỳ trị vì của Raja Raja Chola I, song trong thời gian trị vì của Rajendra Chola I thì Chola tấn công các thành thị của Srivijaya.[22]

Năm 1025 và 1026, Rajendra Chola I tấn công Gangga Negara, vị hoàng đế Tamil được cho là đã tàn phá Kota Gelanggi. Kedah nằm trên tuyến đường xâm chiếm và do Chola cai trị từ năm 1025. Một cuộc xâm chiếm thứ nhì do Virarajendra Chola lãnh đạo, ông ta chinh phục Kedah vào cuối thế kỷ 11.[23] Virarajendra Chola dập tắt một cuộc nổi dậy tại Kedah nhằm lật đổ những người xâm chiếm. Việc người Chola tiến đến làm giảm uy thế của Srivijaya, vốn có ảnh hưởng đến Kedah, Pattani và xa đến Ligor. Trong thời gian trị vì của Kulothunga Chola I, quyền bá chủ của Chola được thiết lập tại Kedah trong cuối thế kỷ 11.[24]

Một bài thơ Tamil thế kỷ thư hai 2 tên là Pattinapalai mô tả về hàng hóa từ Kedaram (Kedah) chất đầy trên đường phố kinh thành Chola. Một kịch của Ấn Độ thế kỷ 7 mang tên Kaumudhimahotsva đề cập đến Kedah với tên Kataha-nagari.

Agnipurana cũng đề cập đến một lãnh thổ gọi là Anda-Kataha với một đoạn biên giới được xác định bằng một đỉnh núi cao, được các học giả cho là núi Jerai. Các câu chuyện từ Katasaritasagaram mô tả tính thanh lịch trong sinh hoạt tại Kataha.

Vương quốc Ligor theo Phật giáo sau đó đoạt quyền kiểm soát Kedah, quốc vương Ligor là Chandrabhanu sử dụng Kedah làm một căn cứ để tấn công Sri Lanka trong thế kỷ 11, một sự kiện được ghi trong một bản khắc đá tại Nagapattinum thuộc Tamil Nadu và trong biên niên sử Mahavamsa của Sri Lanka.

Đương thời, vương quốc Miên, Xiêm, và thậm chí Chola nỗ lực nhằm kiểm soát các tiểu quốc Mã Lai.[14] Quyền lực của Srivijaya suy yếu từ thế kỷ 12 do quan hệ giữa kinh thành và các chư hầu bị tan vỡ.

Chiến tranh với người Java khiến Srivijaya phải cầu viện Trung Hoa, và chiến tranh với các quốc gia Ấn Độ cũng khả nghi.

Trong thế kỷ 11, quyền lực rời đến Melayu, một cảng có thể nằm xa hơn về nội lục tại Sumatra và ven sông Jambi.[21] Quyền lực của các Maharaja Phật giáo bị suy yếu hơn nữa khi Hồi giáo được truyền bá. Các khu vực sớm cải sang Hồi giáo như Aceh tách khỏi quyền kiểm soát của Srivijaya. Đến cuối thế kỷ 13, các quốc vương của Sukhothai khống chế đại bộ phận Malaysia bán đảo.

Trong thế kỷ 14, Đế quốc Majapahit Ấn Độ giáo có căn cứ tại Java tiến hành thuộc địa hóa bán đảo.[20]

Hồi giáo truyền bá

Hồi giáo truyền đến quần đảo Mã Lai thông qua những thương nhân Ả Rập và Ấn Độ trong thế kỷ 13, kết thúc thời kỳ của Ấn Độ giáo và Phật giáo.[11]

Hồi giáo dần tiến đến khu vực, và trở thành tôn giáo của tầng lớp ưu tú trước khi truyền bá đến thường dân. Hồi giáo tại Malaysia chịu ảnh hưởng từ các tôn giáo trước đó và nguyên bản là không chính thống.[14]

Hải cảng Malacca trên bờ biển phía tây của bán đảo Mã Lai được thành lập vào năm 1402 theo lệnh của Parameswara, một hoàng tử của Srivijaya tẩu thoát khỏi Temasek (nay là Singapore)[14]. Sau khi tẩu thoát, Parameswara tiến về phía bắc để thành lập một khu định cư. Tại Muar, Parameswara cân nhắc đặt quốc gia mới của mình tại Biawak Busuk hoặc là Kota Buruk. Nhận thấy vị trí của Muar không phù hợp, ông tiếp tục đi về phía bắc. Ông tiến đến một làng cá tại cửa sông Bertam (tên cũ của sông Melaka), và thành lập khu định cư mà sau phát triển thành Vương quốc Malacca. Theo Biên niên sử Mã Lai, tại đây Parameswara trông thấy một con cheo cheo đá một con chó nghỉ bên dưới một cây Malacca, ông cho rằng đây là một điềm lành nên quyết định kiến lập một vương quốc mang tên Malacca. Ông cho xây dựng và cải tiến hạ tầng cho mậu dịch, Vương quốc Malacca thường được nhìn nhận là quốc gia độc lập đầu tiên tại bán đảo.[25]

Vào giữa thế kỷ 15, công chúa Trung quốc là Hán Lệ Bảo người vùng Phúc Kiến, được gả cho quốc vương Malacca, vua Mansur Shah. Công chúa đi cùng với đoàn tùy tùng và di dân của mình - gồm 500 con trai của các quan vài trăm cung nữ. Đoàn người này cuối cùng định cư tại Bukit Cina ở Malacca. Hậu duệ của những người này, sinh ra từ các cuộc hôn nhân với dân bản xứ, ngày nay được biết đến như là những người Peranak: Baba (tước hiệu của đàn ông) và Nyonya (tước hiệu của đàn bà).

Bukit China

Bukit China (Malay: "Chinese Hill"; Chinese: 三宝山) Núi Tam Bảo is a hillside of historical in the capital of Malaysian state of Malacca, Malacca City.

Đổi lại, việc được triều cống thường lệ, hoàng đế Đại Minh cũng cung cấp sự bảo hộ cho Malacca trước đe dọa liên tục về một cuộc tấn công của Xiêm.

Người Hoa và người Ấn định cư tại bán đảo mã Lai trước và trong giai đoạn này là tổ tiên của cộng đồng Baba-Nyonya và Chetti hiện nay.

Theo một giả thuyết, Parameswara trở thành một người Hồi giáo khi ông kết hôn với một công chúa của Pasai và lấy tước hiệu Ba Tư là "Shah", tự xưng là Iskandar Shah.[26] Biên niên sử Trung Hoa đề cập rằng vào năm Vĩnh Lạc thứ 9 (1414), con trai của quân chủ đầu tiên của Malacca đến chầu hoàng đế Đại Minh để thông báo rằng cha mình đã từ trần.

Con trai của Parameswara sau đó được hoàng đế Đại Minh chính thức công nhận là quân chủ thứ nhì của Malacca, mang tước Raja Sri Rama Vikrama, và được các thần dân Hồi giáo biết đến với tước Sultan Sri Iskandar Zulkarnain Shah hay Sultan Megat Iskandar Shah. Ông cai trị Malacca từ năm 1414 đến năm 1424.[26][27]

Thông qua ảnh hưởng của những người Hồi giáo Ấn Độ, và ở một mức độ thấp hơn là người Hồi từ Trung Quốc, Hồi giáo trở nên ngày càng phổ biến trong thế kỷ 15.

Sau một giai đoạn ban đầu triều cống cho Ayutthaya,[14] Malacca nhanh chóng đàm nhận vị trí trước đây của Srivijaya, thiết lập quan hệ độc lập với Đại Minh, và khai thác vị trí chi phối eo biển Malacca để kiểm soát mậu dịch hàng hải Trung-Ấn, vốn trở nên ngày càng quan trọng, trong khi các cuộc chinh phục của người Mông Cổ cũng đã cắt đứt tuyến đường bộ giữa Trung Hoa và phương Tây.

Trong vòng vài năm sau khi thành lập, Malacca chính thức chấp nhận Hồi giáo. Parameswara trở thành một người Hồi giáo, và do vậy việc cải biến tôn giáo của người Mã Lai sang Hồi giáo được tăng tốc trong thế kỷ 15.[20] Quyền lực chính trị của Malacca giúp truyền bá nhanh chóng Hồi giáo trên khắp quần đảo. Malacca là một trung tâm thương nghiệp quan trọng vào đương thời, thu hút mậu dịch từ khắp khu vực.[20]

Đến đầu thế kỷ 16, cùng với Malacca trên bản đảo Mã Lai và nhiều bộ phận của Sumatra, vương quốc Demak tại Java, và các vương quốc khác trên khắp quần đảo Mã Lai ngày càng cải sang Hồi giáo,[28] nó trở thành tôn giáo chi phối đối với người Mã Lai, và tiến xa đến Philippines ngày nay.

Vương triều Malacca tồn tại trong hơn một thế kỷ, song trong thời gian này nó trở thành trung tâm của văn hóa Mã Lai. Hầu hết các quốc gia Mã Lai trong tương lai đều bắt nguồn trong giai đoạn này.[11]

Malacca bắt đầu trở thành một trung tâm văn hóa rõ nét, tạo ra mô hình của văn hóa Mã Lai hiện đại: một sự pha trộn của các yếu tố Mã Lai bản địa và các yếu tố Ấn Độ, Trung Hoa và Hồi giáo.

Những phong cách của Malacca trong văn chương, nghệ thuật, âm nhạc, vũ đạo và trang phục, và các tước hiệu trong triều đình, được nhận định là tiêu chuẩn đối với mọi người Mã Lai. Triều đình Malacca cũng đem lại thanh thế lớn cho tiếng Mã Lai, thứ tiếng nguyên tiến hóa tại Sumatra và được đưa đến Malacca khi nó hình thành. Tiếng Mã Lai trở thành ngôn ngữ chính thức của toàn bộ các tieu bang tại Malaysia, song các ngôn ngữ địa phương vẫn tồn tại ở một số nơi.

Sau khi Malacca sụp đổ, Vương quốc Brunei trở thành trung tâm lớn của Hồi giáo trong khu vực.[11]

Đấu tranh vì quyền bá chủ

Đế quốc Ottoman đóng cửa tuyến đường bộ từ châu Á đến châu Âu và thương nhân Ả Rập yêu sách nhằm độc quyền mậu dịch với Ấn Độ và Đông Nam Á, do vậy các cường quốc châu Âu tìm kiếm một tuyến hàng hải. Năm 1511, Afonso de Albuquerque dẫn một đoàn viễn chinh đến Malaya, họ chiếm Malacca với ý định sử dụng nơi này làm một căn cứ cho các hoạt động tại Đông Nam Á.[14] Đây là yêu sách thuộc địa đầu tiên tại khu vực nay là Malaysia.[20] Con trai của Quốc vương Malacca cuối cùng là Sultan Alauddin Riayat Shah II chạy đến cực nam của bán đảo, tại đây ông thành lập một quốc gia mà sau là Vương quốc Johor.[14]

Một người con trai khác kiến lập Vương quốc Perak ở phía bắc. Đến cuối thế kỷ 16, các thương nhân người Âu khám phá các mỏ thiếc tại miền bắc Malaya, và Perak phát triển thịnh vượng nhơ thu nhập từ xuất cảng thiếc.[21] Bồ Đào Nha có ảnh hưởng mạnh mẽ, họ tích cực nỗ lực nhằm cải biến tôn giáo của dân cư Malacca sang Công giáo.[14]

Năm 1571, người Tây Ban Nha chiếm Manila và thiết lập một thuộc địa tại Philippines, làm suy giảm quyền lực của Brunei.[11]

Pháo đài A Famosa tại Malacca được người Bồ Đào Nha xây dựng trong thế kỷ 16.

Sau khi Malacca sụp đổ trước người Bồ Đào Nha, Vương quốc Johor và Vương quốc Aceh tại miền bắc Sumatra lấp đầy khoảng trống quyền lực.[14]

Ba thế lực đấu tranh nhằm thống trị bán đảo Mã Lai và các đảo xung quanh.[21] Johor được thành lập trong bối cảnh Malacca bị chinh phục song phát triển đủ mạnh để cạnh tranh với người Bồ Đào Nha, song không thể tái chiếm thành phố. Thay vào đó, Johor khuếch trương theo các hướng khác, xây dựng trong 130 năm một trong những quốc gia Mã Lai lớn nhất.[14] Trong thời gian này, nhiều nỗ lực nhằm tái chiếm Malacca dẫn đến phản ứng mạnh từ người Bồ Đào Nha, họ thậm chí tấn công đến kinh thành của Johor là Johor Lama vào năm 1587.[14]

Năm 1607, Vương quốc Aceh nổi lên thành một quốc gia hùng cường và thịnh vượng nhất tại quần đảo Mã Lai. Trong thời gian trị vì của Iskandar Muda, quyền kiểm soát của Aceh được khuếch trương ra một số quốc gia Mã Lai. Một cuộc chinh phục đáng chú ý là tại Perak, một quốc gia sản xuất thiếc trên bán đảo.[21] Sức mạnh của hạm đội Aceh kết thúc trong chiến dịch chống Malacca vào năm 1629, khi liên quân Bồ Đào Nha và Johor tiêu diệt toàn bộ tàu và 19.000 quân nhân của Aceh theo tường thuật của Bồ Đào Nha.

Tuy nhiên, quân Aceh chưa bị tiêu diệt do họ có thể chinh phục Kedah trong cùng năm và đưa nhiều dân cư nước này đến Aceh. Một cựu vương tử của Pahang là Iskandar Thani sau đó trở thành Sultan của Aceh. Xung đột nhằm giành quyền kiểm soát eo biển kéo dài cho đến năm 1641, khi đồng minh của Johor là người Hà Lan giành quyền kiểm soát Malacca.

Trong đầu thế kỷ 17, Công ty Đông Ấn Hà Lan được thành lập, và trong thời gian này Hà Lan có chiến tranh với Tây Ban Nha- cùng nằm trong Liên minh Iberia với Bồ Đào Nha. Người Hà Lan lập một liên minh với Johor và sử dụng điều này nhằm đẩy người Bồ Đào Nha khỏi Malacca vào năm 1641.[14] Được người Hà Lan hỗ trợ, Johor thiết lập một quyền bá chủ lỏng đối với các quốc gia Mã Lai, ngoại trừ Perak do nước này có thể kích động Johor chống Xiêm và duy trì độc lập. Người Hà Lan không can thiệp trong những sự vụ địa phương tại Malacca, nhưng đồng thời chuyển hầu hết giao dịch đến các thuộc địa của họ trên đảo Java.[14]

Nhược điểm của các tiểu quốc Mã Lai duyên hải dẫn đến người Bugis nhập cư, họ thoát khỏi sự thực dân hóa của Hà Lan tại Sulawesi, thiết lập nhiều khu định cư trên bán đảo và sử dụng chúng để gây trở ngại cho mậu dịch của người Hà Lan.[14] Họ đoạt quyền kiểm soát Johor sau khi ám sát Sultan cuối cùng của dòng vương thất Malacca cũ vào năm 1699. Người Bugis khuếch trương quyền lực của mình tại các quốc gia Johor, Kedah, Perak, và Selangor.[14] Người Minangkabau từ trung tâm Sumatra di cư đến Malaya, và cuối cùng thiết lập quốc gia riêng của họ là Negeri Sembilan. Sự sụp đổ của Johor để lại một khoảng trống quyền lực trên bán đảo Mã Lai, thế lực lấp đầy một phần là Ayutthaya, quốc gia Xiêm La này biến năm quốc gia Mã Lai ở phía bắc là Kedah, Kelantan, Pattani, Perlis, và Terengganu làm chư hầu. Việc Johor suy yếu cũng khiến Perak trở thành thủ lĩnh của các quốc gia Mã Lai.

Tầm quan trọng kinh tế của Malaya đối với châu Âu phát triển nhanh chóng trong thế kỷ 18. Mậu dịch trà phát triển nhanh giữa Trung Hoa và Anh làm gia tăng nhu cầu về thiếc Malaya có chất lượng cao để làm hòm đựng trà. Tiêu Malaya cũng có danh tiếng tại châu Âu, trong khi Kelantan và Pahang có những mỏ vàng. Sự phát triển của khai thác thiếc và vàng và những ngành dịch vụ liên quan dẫn đến dòng người định cư ngoại quốc đầu tiên đến thế giới Mã Lai—ban đầu là người Ả Rập và Ấn Độ, sau đó là người Hoa—họ định cư tại các đô thị và sớm chi phối các hoạt động kinh tế. Điều này thiết lập một mô hình đặc trưng cho xã hội Malaya trong 200 năm tiếp theo, đó là dân cư Mã Lai nông thôn ngày càng nằm dưới quyền chi phối của các cộng đồng nhập cư đô thị thịnh vượng.

Ảnh hưởng của Anh

Những thương nhân người Anh hiện diện trong hải phận Mã Lai từ thế kỷ 17. Trước giữa thế kỷ 19, quan tâm của Anh trong khu vực chủ yếu là về kinh tế, ít quan tâm đến kiểm soát lãnh thổ. Khi đã là thế lực thuộc địa hóa hùng mạnh nhất tại Ấn Độ, Anh hướng về Đông Nam Á nhằm tìm kiếm tài nguyên mới.[14] Sự phát triển của mậu dịch với Trung Quốc của các tàu của Anh làm tăng mong muốn đặt căn cứ trong khu vực. Nhiều đảo được sử dụng cho mục đích này, song đảo đầu tiên thu được lâu dài là Penang, thuê từ Sultan của Kedah vào năm 1786.[29] Ngay sau đó là việc thuê một khu vực lãnh thổ trên đại lục đối diện với Penang (gọi là tỉnh Wellesley). Năm 1795, trong Các cuộc chiến tranh của Napoléon, được sự tán thành của Hà Lan, người Anh chiếm đóng Malacca thuộc Hà Lan nhằm ngăn chặn khả năng Pháp quan tâm đến khu vực.[20]

Khi Malacca được trao trả cho Hà Lan vào năm 1815, thống đốc của Anh là Stamford Raffles tìm kiếm một căn cứ thay thế, và đến năm 1819 ông thu được Singapore từ Sultan của Johor.[30] Việc trao đổi thuộc địa Bencoolen lấy Malacca với người Hà Lan khiến Anh trở thành thế lực thực dân duy nhát trên bán đảo Mã Lai.[14] Các lãnh thổ của Anh được thiết lập với vị thế là các cảng tự do, nỗ lực nhằm phá vỡ độc quyền của các thế lực thực dân khác đương thời, và biến chúng thành những cơ sở mậu dịch lớn. Chúng cho phép Anh kiểm soát toàn bộ mậu dịch thông qua eo biển Malacca.[14] Ảnh hưởng của Anh gia tăng khi người Malaya lo sợ trước sự bành trướng của Xiêm, khi Anh trở thành một đối trọng hữu dụng. Trong thế kỷ 19, các Sultan Mã Lai liên kết bản thân với Đế quốc Anh do những lợi ích của việc liên hiệp với Anh và tin tưởng vào nền văn minh cao cấp của Anh.[21]

Năm 1824, quyền bá chủ của Anh tại Malaya được chính thức hóa theo Hiệp định Anh-Hà Lan, theo đó phân chia khu vực Mã Lai giữa Anh và Hà Lan. Người Hà Lan rút khỏi Malacca[20] và từ bỏ toàn bộ quyền lợi tại Malaya, trong khi Anh công nhận quyền cai trị của Hà Lan đối với phần còn lại của Đông Ấn. Đến năm 1826, Anh kiểm soát Penang, Malacca, Singapore, và đảo Labuan, chúng được hợp thành thuộc địa vương thất Các khu định cư Eo biển,[14] ban đầu nằm dưới quyền hành chính của Công ty Đông Ấn Anh cho đến năm 1867, sau đó được chuyển cho Bộ Thuộc địa tại Luân Đôn.[21]

Ban đầu, người Anh tuân theo một chính sách không can thiệp vào quan hệ giữa các quốc gia Mã Lai.[21][31] Tầm quan trọng thương nghiệp của khai thác thiếc tại các quốc gia Mã Lai đối với thương nhân tại Các khu định cư Eo biển dẫn đến đấu tranh giữa tầng lớp quý tộc trên bán đảo. Sự bất ổn của những quốc gia này gây tổn thất cho thương nghiệp trong khu vực, dẫn đến sự can thiệp của người Anh. Sự thịnh vượng của hoạt động khai thác thiếc tại Perak khiến người Anh ưu tiên thực hiện ổn định chính trị tại đây, và Perak do đó trở thành quốc gia Mã Lai đầu tiên chấp thuận sự giám sát của một thống sứ người Anh.[14] Ngoại giao pháo hạm của Anh được sử dụng nhằm đem lại một giải pháp hòa bình cho nội loạn có nguyên nhân từ các băng đảng người Hoa và Mã Lai trong một đấu tranh chính trị. Hiệp định Pangkor 1874 mở đường cho việc khuếch trương ảnh hưởng của Anh tại Malaya. Người Anh dàn xếp các hiệp định với một số quốc gia Mã Lai, đặt chức "thống sứ" để cố vấn cho các Sultan và ngay sau đó trở thành người cai trị thực tế tại các quốc gia đó.[32] Những cố vấn này nằm giữ mọi quyền lực ngoại trừ tôn giáo và phong tục Mã Lai.[14]

Một mình Johor kháng cự bằng cách hiện đại hóa và trao sự bảo hộ pháp lý cho các nhà đầu tư Anh và Hoa. Bước sang thế kỷ 20, các quốc gia Pahang, Selangor, Perak, và Negeri Sembilan, được gọi chung là các quốc gia Mã Lai liên bang, có các cố vấn người Anh.[14] Năm 1909, Xiêm buộc phải nhượng Kedah, Kelantan, Perlis và Terengganu, vốn đã có các cố vấn người Anh, cho Anh.[14] Sultan Abu Bakar của Johor và Nữ vương Victoria có quen biết cá nhân và công nhận nhau bình đẳng. Cho đến năm 1914, người kế vị của Sultan Abu Bakar là Sultan Ibrahim chấp thuận một cố vấn người Anh. Bốn quốc gia nguyên là chư hầu của Xiêm, cùng với Johor được gọi là Các quốc gia Mã Lai phi liên bang. Các quốc gia nằm dưới quyền kiểm soát hầu như là trực tiếp của Anh trải qua phát triển nhanh chóng, trở thành những nhà cung cấp lớn nhất trên thế giới về thiếc, rồi cao su.[14]

Vào cuối thế kỷ 19, người Anh cũng giành quyền kiểm soát bờ biển phía bắc của Borneo, tại đây quyền cai trị của người Hà Lan chưa từng được thiết lập. Phát triển trên bán đảo Mã Lai và Borneo về đại thể là tách biệt cho đến thế kỷ 19.[33]

Phần phía đông của khu vực này (nay là Sabah) nằm dưới quyền kiểm soát danh nghĩa của Quốc vương Sulu, một chư hầu của Philippines thuộc Tây Ban Nha. Phần còn lại là lãnh thổ của Vương quốc Brunei. Năm 1841, nhà phiêu lưu người Anh James Brooke giúp Sultan của Brunei trấn áp một cuộc phản loạn, và đổi lại được nhận tước hiệu raja và quyển quản lý huyện sông Sarawak. Năm 1846, tước hiệu của ông được công nhận là có quyền thế tập, và các "Rajah da trắng" bắt đầu cai trị Sarawak như một quốc gia độc lập được công nhận. Nhà Brooke khuếch trương Sarawak cùng với tổn thất lãnh thổ của Brunei.[14]

Năm 1881, Công ty Bắc Borneo thuộc Anh được trao quyền kiểm soát lãnh thổ Bắc Borneo thuộc Anh, bổ nhiệm một thống đốc và cơ quan lập pháp, được cai trị từ văn phòng tại Luân Đôn. Tình trạng của nó là tương tự như một lãnh thổ bảo hộ của Anh, và nó khuếch trương lãnh thổ vào Brunei giống như Sarawak.[14] Philippines chưa từng công nhận việc mất lãnh thổ của Sultan của Sulu, sau đó yêu sách với miền đông Sabah. Năm 1888, phần còn lại của Brunei trở thành một lãnh thổ bảo hộ của Anh, và đến năm 1891 một hiệp định Anh-Hà Lan chính thức thiết lập biên giới giữa hai phần Borneo thuộc Anh và Hà Lan.

Đến năm 1910, mô hình cai trị của Anh tại các lãnh thổ Mã Lai được thiết lập. Các khu định cư Eo biển là một thuộc địa vương thất, cai trị bởi một thống đốc dưới quyền giám sát của Bộ Thuộc địa tại Luân Đôn. Dân cư tại đó có một nửa là người Hoa, song toàn bộ dân cư bất kể chủng tộc đều là thần dân của Anh.

Bốn quốc gia đầu tiên chấp thuận thống sứ người Anh là Perak, Selangor, Negeri Sembilan, và Pahang độc lập về phương diện pháp lý, song thực tế là thuộc địa của Anh. Johor, Kedah, Kelantan, Perlis, và Terenggan có mức độ độc lập cao hơn một chút, song họ không thể kháng cự lâu ý muốn đặt thống sứ người Anh. Johor là đồng minh mật thiết nhất của Anh trong các sự vụ Mã Lai, có đặc quyền về một hiến pháp thành văn, theo dó trao cho Sultan quyền bổ nhiệm nội các của mình, song ông thường cẩn trọng tham vấn trước với người Anh.[31]

Tiến hóa của Malaysia

Chiến tranh và tình trạng khẩn cấp

Tugu Negara, đài tưởng niệm quốc gia của Malaysia dành cho những người hy sinh trong Chiến tranh thế giới thứ hai và Tình trạng khẩn cấp Malaya.

Trong Chiến tranh thế giới thứ nhất, tàu tuần dương Zhemchug của Nga bị tàu tuần dương Emden của Đức đánh đắm vào ngày 28 tháng 10 năm 1914 trong trận Penang.

Chiến tranh thế giới thứ hai tại Thái Bình Dương bùng nổ trong tháng 12 năm 1941, song người Anh tại Malaya thể hiện rằng họ hoàn toàn không có chuẩn bị. Trong thập niên 1930, dự đoán mối đe dọa tăng lên từ năng lực hải quân của Nhật Bản, họ xây dựng một căn cứ hải quân lớn tại Singapore, song chưa từng tiên liệu một cuộc xâm chiếm Malaya từ phía bắc. Do nhu cầu chiến tranh tại châu Âu, Anh Quốc hầu như không có năng lực không quân tại Viễn Đông. Người Nhật do đó có thể tấn công từ các căn cứ của họ tại Đông Dương thuộc Pháp mà không chịu tổn thất, bất chấp kháng cự từ các lực lượng Anh, Úc, và Ấn Độ, người Nhật tràn ngập Malaya chỉ sau hai tháng. Singapore đầu hàng vào tháng 2 năm 1942, Bắc Borneo và Brunei cũng bị người Nhật chiếm đóng.

Những nhà dân tộc chủ nghĩa người Mã Lai vốn chủ trương Melayu Raya đã cộng tác với người Nhật dựa trên quan điểm rằng Nhật Bản sẽ hợp nhất Đông Ấn Hà Lan, Malaya và Borneo và trao cho họ quyền độc lập.[34] Tuy nhiên, đối với người Hoa thì quân Nhật là kẻ địch, họ bị người Nhật đối xử rất khắc nghiệt: trong sự kiện túc thanh có đến 80.000 người Hoa tại Malaya và Singapore bị sát hại. Người Hoa dưới sự lãnh đạo của Đảng Cộng sản Malaya trở thành trụ cột của Quân đội Nhân dân Malaya kháng Nhật (MPAJA). Người Nhật làm tổn thương đến chủ nghĩa dân tộc Mã Lai khi họ cho phép đồng minh là Thái Lan tái thôn tính ba quốc gia phía bắc là Kedah, Perlis, Kelantan, và Terengganu. Việc mất thị trường xuất khẩu tạo ra thất nghiệp hàng loạt tại Malaya, tác động đến các dân tộc và khiến người Nhật ngày càng bị phản đối.

Trong thời gian Nhật Bản chiếm đóng, căng thẳng dân tộc gia tăng và chủ nghĩa dân tộc phát triển.[35] Người Malaya hân hoan khi chứng kiến người Anh trở lại vào năm 1945, song mọi thứ không thể được duy trì như thời tiền chiến, và có mong muốn mạnh mẽ hơn về độc lập.[36] Anh bị phá sản và chính phủ Lao động mới quyết định rút lực lượng khỏi phương Đông sớm nhất có thể. Chính sách của Anh nay là quyền tự trị thuộc địa và cuối cùng là độc lập, và cơn sóng chủ nghĩa dân tộc nhanh chóng tiếp cận Malaya. Tuy nhiên, hầu hết người Mã Lai quan tâm đến việc tự vệ trước Đảng Cộng sản Malaya do người Hoa chi phối nhiều hơn là yêu cầu độc lập từ Anh.

Năm 1944, người Anh lập kế hoạch về một Liên hiệp Malaya, theo đó sẽ hợp nhất các quốc gia Mã Lai liên bang và phi liên bang, cộng thêm Penang và Malacca (nhưng không có Singapore), thành một thuộc địa vương thất duy nhất, với một dự tính hướng đến độc lập. Các lãnh thổ tại Borneo và Singapore bị loại trừ do chúng gây khó khăn trong việc hình thành liên hiệp.[21] Tuy nhiên, điều này bị người Mã Lai phản đối mãnh liệt, họ phản đối sự suy yếu của các quân chủ Mã Lai và việc trao quyền công dân cho người Hoa và các dân tộc thiểu số khác.[37] Người Anh quyết định về quyền bình dẳng giữa các dân tộc do nhận thấy rằng trong đại chiến sự trung thành với Anh của người Hoa và người Ấn cao hơn so với người Mã Lai.[21] Các Sultan ban đầu ủng hộ kế hoạch, song sau đó thoái lui và đứng đầu hoạt động kháng cự.

Năm 1946, Tổ chức Dân tộc Mã Lai Thống nhất (UMNO) được những nhà dân tộc chủ nghĩa Mã Lai thành lập, đứng đầu là Thủ hiến Johor Dato Onn bin Jaafar.[21] UMNO chủ trương độc lập cho Malaya, song chỉ khi quốc gia mới do người Mã Lai độc quyền điều hành. Đối diện trước phản đối của người Mã Lai, người Anh từ bỏ kế hoạch về quyền công dân bình đẳng. Liên hiệp Malaya được thành lập vào năm 1946 bị bãi bỏ vào năm 1948 và thay thế bằng Liên bang Malaya, theo đó khôi phục quyền tự trị của các quân chủ các quốc gia Mã Lai dưới quyền bảo hộ của Anh.

Trong khi đó, những người Cộng sản chuyển hướng sang nổi dậy công khai. Quân đội Nhân dân Malaya kháng Nhật bị giải tán vào tháng 12 năm 1945, và Đảng Cộng sản Malaya được tổ chức thành một chính đảng hợp pháp, song vũ khí của quân đội này được lưu trữ cẩn thận để sử dụng trong tương lai. Chính sách của Đảng Cộng sản Malaya là lập tức độc lập với quyền bình đẳng đầy đủ cho toàn bộ các dân tộc. Sức mạnh của Đảng Cộng sản Malaya nằm trong các thương hội do người Hoa chi phối đặc biệt là tại Singapore, và trong các trường học Hoa ngữ. Trong tháng 3 năm 1947, Trần Bình trở thành thủ lĩnh của Đảng Cộng sản Malaya, từ đó tổ chức này ngày càng hành động trực tiếp. Phiến quân dưới sự lãnh đạo của Đảng Cộng sản Malaya phát động các chiến dịch du kích nhằm đẩy người Anh ra khỏi Malaya. Trong tháng 7, sau một loạt vụ ám sát những người quản lý đồn điển, chính phủ thuộc địa phán kích, tuyên bố một tình trạng khẩn cấp, cấm chỉ Đảng Cộng sản Malaya và bắt giữ hàng trăm chiến binh của Đảng này. Đảng Cộng sản Malaya triệt thoái vào trong khu vực rừng và thành lập Quân Giải phóng Nhân dân Malaya, với khoảng 13.000 người có vũ trang, toàn bộ đều là người Hoa.

Tình trạng khẩn cấp Malaya kéo dài từ năm 1948 đến năm 1960, và liên quan đến một chiến dịch chống nổi dậy kéo dài do quân đội Thịnh vượng chung tiến hành tại Malaya. Chiến lược của Anh là cô lập Đảng Cộng sản Malaya khỏi các cơ sở ủng hộ của họ bằng cách kết hợp các nhượng bộ về kinh tế và chính trị cho người Hoa và tái định cư người Hoa khai hoang vào những "Tân thôn" trong những vùng không nằm dưới ảnh hưởng của Đảng Cộng sản Malaya, hành động này cuối cùng giành được thành công. Việc huy động có hiệu quả người Mã Lai chống Đảng Cộng sản Malaya cũng là một phần quan trọng trong chiến lược của Anh. Từ năm 1949, chiến dịch của Đảng Cộng sản Malaya bị mất động lượng và việc tuyển mộ giảm mạnh. Đảng Cộng sản Malaya ám sát thành công Cao ủy người Anh Henry Gurney trong tháng 10 năm 1951, song do chuyển sang chiến lược khủng bố nên Đảng Cộng sản Malaya bị nhiều người Hoa ôn hòa xa lánh. Cao ủy mới của Anh là Gerald Templer đến vào năm 1952, bắt đầu sự kết thúc Tình trạng khẩn cấp. Templer phát minh ra các phương pháp chống chiến tranh nổi dậy tại Malaya và áp dụng chúng một cách tàn nhẫn. Mặc dù vậy, lực lượng nổi dậy bị quân Thịnh vượng chung đánh bại vẫn nằm trong bối cảnh Chiến tranh Lạnh.[38] Trong bối cảnh đó, độc lập cho Liên bang trong Thịnh vượng chung được trao ngày 31 tháng 8 năm 1957,[39] với Tunku Abdul Rahman là thủ tướng đầu tiên.[20]

Hướng tới Malaysia

Dataran Merdeka (quảng trường Độc lập) tại Kuala Lumpur, nơi người Malaysia tổ chức ngày độc lập vào 31 tháng 8 hàng năm.

Phản ứng của người Hoa chống Đảng Cộng sản Malaya thể hiện thông qua việc hình thành Công hội người Hoa Malaya (MCA) vào năm 1949, một phương tiện để biểu thị chính kiến của người Hoa ôn hòa. Người lãnh đạo tổ chức là Trần Trinh Lộc tán thành một chính sách cộng tác với Tổ chức Dân tộc Mã Lai Thống nhất nhằm giành độc lập cho Malaya và một chính sách về quyền công dân bình đẳng, song với những nhượng bộ đủ để người Mã Lai giảm bớt lo ngại. Trần Trinh Lộc thiết lập cộng tác mật thiết với Tunku Abdul Rahman, thủ hiến của Kedah và từ năm 1951 là người kế nhiệm Datuk Onn làm lãnh đạo của UMNO. Do người Anh tuyên bố vào năm 1949 rằng Malaya sẽ sớm được độc lập có chăng là người Malaya thích điều này hay không, cả hai nhà lãnh đạo nhất quyết tiến đến một thỏa thuận rằng các cộng đồng của họ có thể sống trong nền tảng của một quốc gia độc lập ổn định. Liên minh UMNO-MCA sau đó tiếp nhận thêm Đại hội người Ấn Malaysia (MIC), giành thắng lợi thuyết phục trong các cuộc bầu cử cấp địa phương và cấp bang trong cả các khu vực người Mã Lai và người Hoa từ năm 1952 đến năm 1955.[40]

Việc khởi đầu chính quyền địa phương được tuyển cử là một bước quan trọng khác nhằm đánh bại Cộng sản. Sau khi Joseph Stalin từ trần vào năm 1953, có sự chia rẽ trong giới lãnh đạo của Đảng Cộng sản Malaya xung quanh việc tiếp tục đấu tranh vũ trang. Nhiều chiến binh của Đảng Cộng sản Malaya mất nhiệt huyết và trở về quê, và đến khi Templer rời Malaya vào năm 1954 thì Tình trạng khẩn cấp chấm dứt, song Trần Bình lãnh đạo một nhóm ẩn náu dọc biên giới Thái Lan trong nhiều năm.

Trong năm 1955 và 1956, Tổ chức Dân tộc Mã Lai Thống nhất, Công hội người Hoa Malaya, và người Anh tìm ra một giải quyết hiến pháp cho nguyên tắc quyền công dân bình đẳng đối với mọi dân tộc. Đổi lại, Công hội người Hoa Malaya chấp thuận rằng nguyên thủ quốc gia của Malaya sẽ xuất thân từ những Sultan người Mã Lai, rằng tiếng Mã Lai sẽ là ngôn ngữ chính thức, và rằng giáo dục tiếng Mã Lai và phát triển kinh tế trong cộng đồng Mã Lai sẽ được xúc tiến và trợ cấp. Trên thực tế, điều này có nghĩa là Malaya sẽ do người Mã Lai điều hành, đặc biệt là họ sẽ tiếp tục chi phối các dịch vụ dân sự, quân đội và cảnh sát, song người Hoa và người Ấn sẽ có đại diện theo tỷ lệ trong Nội các và nghị viện, sẽ điều hành các bang mà họ chiếm đa số, và vị thế kinh tế của họ sẽ được bảo vệ.

Sau khi Nhật Bản đầu hàng, gia tộc Brooke và Công ty Bắc Borneo thuộc Anh từ bỏ quyền kiểm soát của họ tại Sarawak và Bắc Borneo, và những lãnh thổ này trở thành thuộc địa vương thất Anh. Hai lãnh thổ kém phát triển hơn nhiều về mặt kinh tế so với Malaya, và các lãnh đạo chính trị địa phương quá bạc nhược để yêu cầu độc lập. Singapore có phần lớn dân cư là người Hoa và giành được quyền tự trị vào năm 1955, và đến năm 1959 nhà lãnh đạo xã hội Lý Quang Diệu trở thành thủ tướng. Sultan của Brunei duy trì vị thế đối tác của Anh dựa vào tài nguyên dầu mỏ phong phú. Từ năm 1959 đến 1962, chính phủ Anh sắp xếp đàm phán giữa các nhà lãnh đạo địa phương này và chính phủ Malaya.

Năm 1961, Abdul Rahman nêu lên ý tưởng hình thành "Malaysia" bao gồm các thuộc địa của Anh là Brunei, Malaya, Bắc Borneo, Sarawak, và Singapore. Lý do đằng sau là nhằm tạo điều kiện để chính phủ trung ương kiểm soát và chống lại các hoạt động cộng sản, đặc biệt là tại Singapore. Cũng có lo ngại rằng nếu Singapore độc lập thì nơi đây sẽ trở thành một căn cứ cho những người theo chủ nghĩa Chauvin Trung Hoa đe dọa đến chủ quyền của Malaya. Nhằm cân bằng thành phần dân tộc của quốc gia mới, các lãnh thổ mà người Mã Lai và người bản địa chiếm đa số tại miền bắc Borneo cũng được kết hợp, họ sẽ giúp áp chế người Hoa tại Singapore.[41]

Mặc dù Lý Quang Diệu ủng hộ đề xuất, song những đối thủ của ông trong Mặt trận Xã hội Singapore thì phàn đối, cho rằng đây là một âm mưu để người Anh tiếp tục kiểm soát khu vực. Hầu hết các chính đảng tại Sarawak cũng phản đối hợp nhất, và tại Bắc Borneo dù không có chính đảng song các đại diện cộng đồng cũng tuyên bố rằng họ phản đối. Quốc vương của Brunei ủng hộ hợp nhất, song Đảng Nhân dân Brunei phản đối. Tại Hội nghị các thủ tướng Thịnh vượng chung năm 1961, Abdul Rahman giải thích thêm về đề xuất của mình cho những người phản đối. Trong tháng 10, ông đạt được đồng thuận từ chính phủ Anh về kế hoạch, miễn là được sự tán đồng từ các cộng đồng liên quan.

Ủy ban Cobbold tiến hành nghiên cứu tại các lãnh thổ Borneo và tán thành hợp nhất đối với Bắc Borneo và Sarawak; tuy nhiên phát hiện rằng một lượng đáng kể người Brunei phản đối hợp nhất. Bắc Borneo đề ra một danh sách gồm 20 điểm, đề xuất các điều kiện để lãnh thổ gia nhập liên bang mới. Sarawak chuẩn bị một bị vong lục tương tự với 18 điều. Một số điểm trong các thỏa thuận được đưa vào hiến pháp liên bang, một số được chấp thuận bằng miệng. Những bị vong lục này thường được trích dẫn bởi những người cho rằng quyền của Sarawak và Bắc Borneo bị xói mòn theo thời gian. Một cuộc trưng cầu dân ý được tiến hành tại Singapore nhằm đánh giá quan điểm, và 70% ủng hộ hợp nhất với quyền tự trị đáng kể cho chính phủ bang.[42][43] Vương quốc Brunei rút khỏi kế hoạch hợp nhất do phản đối từ một bộ phận đáng kể dân cư cũng như tranh luận về việc nộp thuế tài nguyên dầu mỏ và địa vị của Sultan trong kế hoạch hợp nhất.[31][40][44][45] Ngoài ra, Đảng Nhân dân Brunei tổ chức một cuộc nổi dậy vũ trang, và mặc dù bị dập tắt song điều này được cho là có khả năng gây bất ổn cho quốc gia mới.[46]

Sau khi tái xét kết quả nghiên cứu của Ủy ban Cobbold, chính phủ Anh bổ nhiệm Ủy ban Landsdowne nhằm soạn thảo một hiến pháp cho Malaysia. Hiến pháp cuối cùng về cơ bản là tương tự như hiến pháp năm 1957, song có một số diễn đạt lại như công nhận vị thế đặc biệt của những người bàn địa tại các bang trên đảo Borneo. Bắc Borneo, Sarawak và Singapore cũng được trao một số quyền tự trị mà các bang của Malaya không có. Sau các cuộc đàm phán trong tháng 7 năm 1963, một sự đồng thuận đạt được rằng Malaysia sẽ hình thành vào ngày 31 tháng 8 năm 1963, gồm có Malaya, Bắc Borneo, Sarawak và Singapore. Tuy nhiên, Philippines và Indonesia kịch liệt phản đối tiến triển này, Indonesia tuyên bố Malaysia đại diện cho một hình thức "chủ nghĩa tân thực dân" và Philippines tuyên bố Bắc Borneo là lãnh thổ của mình. Phản đối từ chính phủ Indonesia với nguyên thủ là Sukarno và các nỗ lực của Đảng Liên hiệp Nhân dân Sarawak trì hoãn việc hình thành Malaysia.[47] Do những yếu tố này, một nhóm gồm tám thành viên Liên Hợp Quốc được thành lập để tái xác định liệu Bắc Borneo và Sarawak có thực tâm mong muốn gia nhập Malaysia hay không.[48][49] Malaysia chính thức xuất hiện vào ngày 16 tháng 9 năm 1963, gồm có Malaya, Bắc Borneo, Sarawak, và Singapore, tổng dân số là khoảng 10 triệu.

Thách thức sau độc lập

Thời điểm độc lập, Malaya có những lợi thế lớn về kinh tế, nằm trong số những nhà sản xuất hàng đầu thế giới về ba mặt hàng có giá trị là cao su, thiếc và dầu cọ, và cũng là một nhà sản xuất quặng sắt quan trọng. Những ngành công nghiệp xuất khẩu cho phép chính phủ Malaya có thặng dư cao về tài chính để đầu tư cho các dự án phát triển công nghiệp và hạ tầng. Trong thập niên 1950 và 1960, Malaya và sau là Malaysia đặt trọng tâm và kế hoạch quốc gia, song Tổ chức Dân tộc Mã Lai Thống nhất chưa từng là một đảng xã hội. Các kế hoạch Malaya thứ nhất và thứ nhì (1956–60 và 1961–65) kích thích tăng trưởng kinh tế thông qua đầu tư quốc gia trong công nghiệp và tu sửa cơ sở hạ tầng như đường và cảng vốn bị hư hại và bỏ quên trong chiến tranh và Tình trạng khẩn cấp. Chính phủ quan tâm đến việc giảm sự phụ thuộc của Malaya vào xuất khẩu hàng hóa, và cũng nhận thức được rằng nhu cầu về cao su tự nhiên sắp hạ thấp do bị cao su tổng hợp thay thế.

Tổng thống Indonesia Sukarno được sự ủng hộ từ Đảng Cộng sản Indonesia (PKI) và nhìn nhận Malaysia như một âm mưu "chủ nghĩa thực dân mới" chống lại quốc gia của ông, và ủng hộ một cuộc nổi dậy cộng sản tại Sarawak, vốn chủ yếu liên quan đến các thành phần trong cộng đồng người Hoa địa phương. Lực lượng không chính quy của Indonesia xâm nhập Sarawak, song họ bị lực lượng Malaysia và Thịnh vượng chung ngăn chặn.[21] Thời kỳ đối đầu giữa Malaysia và Indonesia về kinh tế, chính trị và quân sự kéo dài cho đến khi Sukarno bị lật đổ vào năm 1966.[20] Philippines phản đối liên bang hình thành, tuyên bố Bắc Borneo là bộ phận của Sulu, và do đó thuộc Philippines.[21] Năm 1966, Tổng thống Ferdinand Marcos từ bỏ yêu sách, song vấn đề vẫn là một điểm gây tranh luận trong quan hệ Philippines-Malaysia.[50][51]

Đại khủng hoảng trong thập niên 1930, tiếp đến là Chiến tranh Trung-Nhật dẫn đến việc kết thúc làn sóng nhập cư của người Hoa đến Malaya. Điều này làm ổn định tình hình nhân khẩu học và kết thúc viễn cảnh người Mã Lai trở thành thiểu số tại quốc gia của họ. Cân bằng về dân tộc bị biến đổi do tác động từ việc hợp nhất Singapore có đa số dân cư là người Hoa, khiến nhiều người Mã Lai lo ngại.[14] Việc thành lập Malaysia khiến tỷ lệ người Hoa lên đến gần 40%. Cả Tổ chức Dân tộc Mã Lai Thống nhất và Công hội người Hoa Malaya đều lo lắng về khả năng Đảng Hành động Nhân dân của Lý Quang Diệu thu hút cử tri tại Malaya, và cố gắng tổ chức một đảng tại Singapore nhằm thách thức vị thế của Lý Quang Diệu tại đây. Đáp lại, Lý Quang Diệu đe dọa cho đảng viên của Đảng Hành động Nhân dân ứng cử tại Malaya trong bầu cử liên bang năm 1964, bất chấp một thỏa thuận trước đó. Căng thẳng dân tộc tăng cường khi Đảng Hành động Nhân dân thành lập một liên minh đối lập với mục tiêu bình đẳng giữa các dân tộc.[21] Điều này kích động Tunku Abdul Rahman yêu cầu Singapore rút khỏi Malaysia, và điều này diễn ra vào tháng 8 năm 1965.[52]

Sự cộng tác của Công hội người Hoa Malaysia và Đại hội người Ấn Malaysia trong các chính sách ưu tiên người Mã Lai khiến vị thế của họ bị suy yếu trong các cử tri người Hoa và người Ấn. Đồng thời, tác động từ các chính sách hành động quả quyết của chính phủ trong các thập niên 1950 và 1960 tạo ra một tầng lớp bất mãn gồm những người Mã Lai có giáo dục song thiếu việc làm. Điều này dẫn đến việc thành lập Mặt trận Nhân dân Malaysia (Gerakan Rakyat Malaysia) vào năm 1968. Đồng thời, Đảng Hồi giáo Malaysia (PAS) và một đảng xã hội của người Hoa mang tên Đảng Hành động Dân chủ (DAP) ngày càng được ủng hộ, lần lượt đe dọa đến UMNO và MCA.[14]

Trong bầu cử liên bang vào tháng 5 năm 1969, Liên minh UMNO-MCA-MIC chỉ giành được 48% số phiếu, song vẫn duy trì thế đa số trong cơ quan lập pháp. Công hội người Hoa Malaysia mất ghế về tay các ứng cử viên của Gerakan hoặc DAP. Phe đối lập mừng thắng lợi bằng cách tổ chức một đoàn xe diễu trên các phố chính của Kuala Lumpur với những người ủng hộ. Lo sợ về những thay đổi dẫn đến phản ứng dữ dội của người Mã Lai, nhanh chóng biến thành bạo loạn và xung đột giữa các cộng đồng với kết quả là khoảng 6.000 nhà và cơ sở kinh doanh của người Hoa bị phóng hỏa và có ít nhất 184 người bị sát hại.[53][54] Chính phủ tuyên bố một tình trạng khẩn cấp, và một Hội đồng điều hành quốc gia của Phó Thủ tướng Tun Abdul Razak đoạt quyền từ chính phủ của Tunku Abdul Rahman, đến tháng 9 năm 1970, Tunku Abdul Rahman buộc phải từ chức để ủng hộ Abdul Razak. Hội đồng gồm 9 thành viên và chủ yếu là người Mã Lai, nắm giữ toàn bộ quyền lực chính trị và quân sự.[14]

Malaysia hiện đại

Kuala Lumpur, một sự pha trộn cổ kim.

Năm 1971, Quốc hội được tái triệu tập, và một liên minh chính phủ mới mang tên Mặt trận Quốc gia (Barisan Nasional) nhậm chức.[14] Liên minh này gồm UMNO, MCA, MIC, Gerakan bị suy yếu nhiều, cùng các đảng khu vực tại Sabah và Sarawak. Đảng Hành động Dân chủ bị loại ra ngoài, chỉ là một đảng đối lập đáng kể. Đảng Hồi giáo Malaysia cũng gia nhập Mặt trận song bị trục xuất vào năm 1977. Abdul Razak nắm quyền cho đến khi mất vào năm 1976 và người kế nhiệm là Hussein Onn, Mahathir Mohamad nhậm chức thủ tướng vào năm 1981 và nắm quyền trong 22 năm.

Dưới thời Mahathir Mohamad, Malaysia trải qua tăng trưởng kinh tế từ thập niên 1980.[55][56] Thời kỳ này cũng diễn ra một sự biến đổi từ kinh tế dựa trên nông nghiệp sang kinh tế dựa trên chế tạo và công nghiệp trong các lĩnh vực như máy tính và điện tử tiêu dùng. Cũng trong giai đoạn này, bộ mặt của Malaysia biến hóa với sự xuất hiện của nhiều siêu dự án, đáng chú ý trong đó là việc xây dựng Tháp đôi Petronas, Sân bay quốc tế Kuala Lumpur, Xa lộ Nam-Bắc, đường đua quốc tế Sepang, và thủ đô hành chính liên bang mới Putrajaya.

Cuối thập niên 1990, Malaysia trải qua náo động do khủng hoảng tài chính châu Á, khủng hoảng tàn phá kinh tế dựa trên lắp ráp của Malaysia. Nhằm ứng phó, Mahathir Mohamad ban đầu tiến hành các chính sách được IMF tán thành, tuy nhiên sự mất giá của Ringgit và suy thoái sâu thêm khiến ông thiết lập chương trình riêng của mình dựa trên việc bảo hộ Malaysia trước các nhà đầu tư ngoại quốc và chấn hưng kinh tế thông qua các dự án xây dựng và hạ lãi suất, các chính sách khiến kinh tế Malaysia khôi phục vào năm 2002. Năm 2003, Mahathir tự nguyện nghỉ hưu để ủng hộ Phó Thủ tướng Abdullah Ahmad Badawi.[14]

Ngày 9 tháng 5 năm 2018, Najib Razak đã thất bại trước cựu Thủ tướng, tiến sĩ Mahathir Mohamad trong cuộc tổng tuyển cử toàn quốc tại Malaysia, chấm dứt 60 năm cầm quyền của Liên minh Mặt trận Dân tộc (BN).[57] Ngày 12 tháng 5 năm 2018, Najib bị cấm không được ra khỏi nước vì các cáo buộc tội tham nhũng.[58][59] Ngày 28 tháng 7 năm 2020, Najib bị tuyên án 12 năm tù và phải nộp phạt 210 triệu ringgit (tương đương 49,3 triệu USD) với tội danh liên quan đến vụ bê bối tham nhũng quỹ đầu tư nhà nước 1Malaysia Development Berhad (1MDB). Đây là lần đầu tiên tòa án của quốc gia này buộc tội một cựu Thủ tướng.[60][61][62]

000000000000000000000

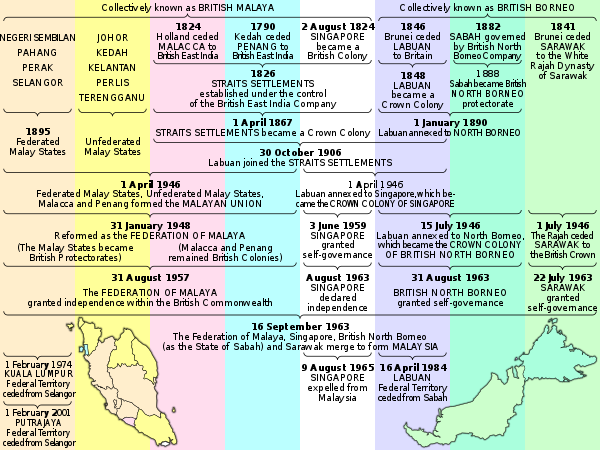

History of Malaysia

| History of Malaysia |

|---|

|

|

|

Malaysia is located on a strategic sea lane that exposes it to global trade and various cultures. The name "Malaysia" is a modern concept, created in the second half of the 20th century. However, contemporary Malaysia regards the entire history of Malaya and Borneo, spanning thousands of years back to prehistoric times, as its own history.

An early western account of the area is seen in Ptolemy's book Geographia, which mentions a "Golden Chersonese" in the 2nd century, now identified as the Malay Peninsula.[1] Hinduism and Buddhism from India and China dominated early regional history, reaching their peak during the reign of the Sumatra-based Srivijaya civilisation, whose influence extended through Sumatra, West Java, East Borneo and the Malay Peninsula from the 7th to the 13th centuries.

Although Muslims passed through the Malay Peninsula as early as the 10th century, it was not until the 14th century that Islam first firmly established itself. The adoption of Islam in the 14th century saw the rise of several sultanates, the most prominent were the Sultanate of Malacca and the Sultanate of Brunei.

The Portuguese were the first European colonial power to establish themselves on the Malay Peninsula and Southeast Asia, capturing Malacca in 1511. This event led to the establishment of several sultanates such as Johor and Perak. Dutch hegemony over the Malay sultanates increased during the course of the 17th to 18th century, capturing Malacca in 1641 with the aid of Johor. In the 19th century, the English, after establishing bases at Jesselton, Kuching, Penang and Singapore, ultimately gained hegemony across the territory that is now Malaysia. The Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1824 defined the boundaries between British Malaya and the Dutch East Indies (which became Indonesia), and the Anglo-Siamese Treaty of 1909 defined the boundaries between British Malaya and Siam (which became Thailand). The fourth phase of foreign influence was a wave of immigration of Chinese and Indian workers to meet the needs created by the colonial economy in the Malay Peninsula and Borneo.[2]

The Japanese invasion during World War II ended British rule in Malaya. The subsequent occupation of Malaya, North Borneo and Sarawak from 1942 to 1945 unleashed a wave of nationalism. After the Empire of Japan was defeated by the Allies, the Malayan Union was established in 1946 by the British administration. Following opposition by the ethnic Malays, led by the United Malays National Organisation (UMNO), the union was reorganized as the Federation of Malaya in 1948 as a protectorate until 1957. In the Peninsula, the Malayan Communist Party (MCP) took up arms against the British and the tension led to the declaration of emergency rule for 12 years from 1948 to 1960. A forceful military response to the communist insurgency, followed by the Baling Talks in 1955, led to Malayan Independence on August 31, 1957, through diplomatic negotiation with the British.[3][4] Tunku Abdul Rahman became the first Prime Minister of Malaysia. The state of emergency was lifted in 1960 when the communist threat subsided as they withdrew to the borders between Malaya and Thailand.

On 16 September 1963, the Federation of Malaysia was formed following the merger of the Federation of Malaya, Singapore, Sarawak, and North Borneo (Sabah). However, in August 1965, Singapore was expelled from the federation and became a separate independent country.[5][6] A confrontation with Indonesia occurred in the early 1960s. A racial riot in 1969, also known as the 13 May incident, brought about the imposition of emergency rule, the suspension of parliament, the establishment of the National Operations Council (NOC), and the proclamation of Rukun Negara by the NOC in 1970, a national philosophy promoting unity among citizens.[7][8] The New Economic Policy (NEP) was adopted in 1971 and stayed in effect until 1991. It sought to eradicate poverty and restructure society to eliminate the identification of race with economic function.[9]

Under Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad, there was a period of rapid economic growth and urbanization in the country beginning in the 1980s. The economy shifted from being agriculturally-based to one based on manufacturing and industry. Numerous megaprojects were completed, such as the Petronas Towers, the North–South Expressway, the Multimedia Super Corridor, and the new federal administrative capital of Putrajaya.[10] Under his tenure, the previous economic policy was succeeded by the National Development Policy (NDP) from 1991 to 2000. The late 1990s Asian financial crisis impacted the country, nearly causing their currency, stock, and property markets to crash; however, they later recovered.[11]

The Barisan Nasional (BN) coalition (previously known as Alliance Party), had ruled Malaysia from 1973 until it was defeated in the 2018 general election by the Pakatan Harapan (PH) coalition.[12] Early in 2020, Malaysia had a political crisis that resulted in the collapse of the PH administration and the formation of Perikatan Nasional (PN), a new coalition government headed by Muhyiddin Yassin of the Malaysian United Indigenous Party (BERSATU).[13] During this time, the country faced a variety of crises, including political, health, social, economic, and cultural crises caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.[14][15] In August 2021, increased infighting between PN and BN led to Muhyiddin being replaced as prime minister by Ismail Sabri of BN.[16] After that, there was a leadership crisis within UMNO (under BN), which led to the earlier 2022 general election and the first-ever hung parliament in the country's history.[17][18] Anwar Ibrahim, a long-time reformist, became Malaysia's tenth prime minister on November 24, 2022, leading the country's first-ever grand coalition government.[19][20]

Prehistory[edit]

Stone hand axes from early hominoids, probably Homo erectus, have been unearthed in Lenggong. They date back 1.83 million years, one of the oldest pieces of evidence of hominid habitation in Southeast Asia.[21]

The earliest evidence of modern human habitation in Malaysia is the 40,000-year-old skull excavated from the Niah Caves in today's Sarawak, nicknamed "Deep Skull". It was excavated from a deep trench uncovered by Barbara and Tom Harrisson (a British ethnologist) in 1958.[22][23][24] This is also one of the oldest modern human skulls in Southeast Asia.[25] The skull most likely belonged to a girl between the ages of 16 and 17.[26] The first foragers visited the West Mouth of Niah Caves (located 110 kilometres (68 mi) southwest of Miri)[23] 40,000 years ago when Borneo was connected to the mainland of Southeast Asia. The landscape around the Niah Caves was drier and more exposed than it is now. Prehistorically, the Niah Caves were surrounded by a combination of closed forests with bush, parkland, swamps, and rivers. The foragers were able to survive in the rainforest through hunting, fishing, and gathering molluscs and edible plants.[26] Mesolithic and Neolithic burial sites have also been found in the area.[27] The area around the Niah Caves has been designated the Niah National Park.[28]

A study of Asian genetics points to the idea that the original humans in East Asia came from Southeast Asia.[29] The oldest complete skeleton found in Malaysia is an 11,000-year-old Perak Man unearthed in 1991.[30] The indigenous groups on the peninsula can be divided into three ethnicities, the Negritos, the Senoi, and the proto-Malays.[31] The first inhabitants of the Malay Peninsula were most probably Negritos.[32] These Mesolithic hunters were probably the ancestors of the Semang, an ethnic Negrito group who have a long history in the Malay Peninsula.[33]

The Senoi appear to be a composite group, with approximately half of the maternal mitochondrial DNA lineages tracing back to the ancestors of the Semang and about half to later ancestral migrations from Indochina. Scholars suggest they are descendants of early Austroasiatic-speaking agriculturalists, who brought both their language and their technology to the southern part of the peninsula approximately 4,000 years ago. They united and coalesced with the indigenous population.[34]

The Proto Malays have a more diverse origin[35] and had settled in Malaysia by 1000 BC as a result of Austronesian expansion.[36] Although they show some connections with other inhabitants in Maritime Southeast Asia, some also have an ancestry in Indochina around the time of the Last Glacial Maximum about 20,000 years ago. Anthropologists support the notion that the Proto-Malays originated from what is today Yunnan, China.[37] This was followed by an early-Holocene dispersal through the Malay Peninsula into the Malay Archipelago.[38] Around 300 BC, they were pushed inland by the Deutero-Malays, an Iron Age or Bronze Age people descended partly from the Chams of Cambodia and Vietnam. The first group in the peninsula to use metal tools, the Deutero-Malays were the direct ancestors of today's Malaysian Malays and brought with them advanced farming techniques.[33] The Malays remained politically fragmented throughout the Malay archipelago, although a common culture and social structure were shared.[39]

Early Hindu-Buddhist kingdoms[edit]

In the first millennium AD, Malay became the dominant ethnicity on the peninsula. The small early states that were established were greatly influenced by Indian culture, as was most of Southeast Asia.[41] Indian influence in the region dates back to at least the 3rd century BC. South Indian culture was spread to Southeast Asia by the South Indian Pallava dynasty in the 4th and 5th centuries.[42]

Trade with India and China[edit]

In ancient Indian literature, the term Suvarnadvipa (Golden Peninsula) is used in the Ramayana; some argue that this is a reference to the Malay Peninsula. The ancient Indian text Vayu Purana also mentions a place named Malayadvipa where gold mines may be found; this term may refer to Sumatra and the Malay Peninsula.[43] The Malay Peninsula was shown on Ptolemy's map as the Golden Chersonese. He referred to the Straits of Malacca as Sinus Sabaricus.[44]

Trade relations with China and India were established in the 1st century BC.[45] Shards of Chinese pottery have been found in Borneo dating from the 1st century following the southward expansion of the Han Dynasty.[46] In the early centuries of the first millennium, the people of the Malay Peninsula adopted the Indian religions of Hinduism and Buddhism, which had a major effect on the language and culture of those living in Malaysia.[47] The Sanskrit writing system was used as early as the 4th century.[48]

Early Kingdoms (3rd–7th centuries)[edit]

There were numerous Malay kingdoms in the 2nd and 3rd centuries, as many as 30, mainly based on the eastern side of the Malay peninsula.[41] Among the earliest kingdoms known to have been based in the Malay Peninsula is the ancient kingdom of Langkasuka, located in the northern Malay Peninsula and based somewhere on the west coast.[41] It was closely tied to Funan in Cambodia, which also ruled parts of northern Malaysia until the 6th century. In the 5th century, the Kingdom of Pahang was mentioned in the Book of Song. According to the Sejarah Melayu ("Malay Annals"), the Khmer prince Raja Ganji Sarjuna founded the kingdom of Gangga Negara (modern-day Beruas, Perak) in the 8th century. Chinese chronicles of the 5th century speak of a great port in the south called Guantoli, which is thought to have been in the Straits of Malacca. In the 7th century, a new port called Shilifoshi is mentioned, and this is believed to be a Chinese rendering of Srivijaya.[citation needed]

Gangga Negara[edit]

Gangga Negara is believed to be a lost semi-legendary Hindu kingdom mentioned in the Malay Annals that covered present-day Beruas, Dinding and Manjung in the state of Perak, Malaysia with Raja Gangga Shah Johan as one of its kings. Gangga Negara means "a city on the Ganges" in Sanskrit,[49] the name derived from Ganganagar in northwest India where the Kambuja peoples inhabited.[citation needed] Researchers believe that the kingdom was centred at Beruas. Another Malay annal Hikayat Merong Mahawangsa known as Kedah Annals, Gangga Negara may have been founded by Merong Mahawangsa's son Raja Ganji Sarjuna of Kedah, allegedly a descendant of Alexander the Great or by the Khmer royalties no later than the 2nd century.[citation needed]

The first research into the Beruas kingdom was conducted by Colonel James Low in 1849 and a century later, by H.G. Quaritch Wales. According to the Museum and Antiquities Department, both researchers agreed that the Gangga Negara kingdom existed between the 1st–11th century but could not ascertain the exact site.[50] For years, villagers had unearthed artefacts believed to be from the ancient kingdoms, most of which are at present displayed at the Beruas Museum. Artefacts on display include a 128 kg cannon, swords, kris, coins, tin ingots, pottery from the Ming Dynasty and various eras, and large jars. They can be dated back to the 5th and 6th centuries.[51]

Old Kedah[edit]

Ptolemy, a Greek geographer, had written about the Golden Chersonese, which indicated that trade with India and China had existed since the 1st century AD.[52]

As early as the 1st century AD, the coastal city-states that existed had a network which encompassed the southern part of the Indochinese peninsula and the western part of the Malay archipelago. These coastal cities had ongoing trade as well as tributary relations with China, at the same time being in constant contact with Indian traders. They seem to have shared a common indigenous culture.[citation needed]

Gradually, the rulers of the western part of the archipelago adopted Indian cultural and political models e.g. proof of such Indian influence on Indonesian art in the 5th century. Three inscriptions found in Palembang (South Sumatra) and on Bangka Island, written in the form of Malay and in alphabets derived from the Pallava script, are proof that the archipelago had adopted Indian models while maintaining their indigenous language and social system. These inscriptions reveal the existence of a Dapunta Hyang (lord) of Srivijaya who led an expedition against his enemies and who curses those who will not obey his law.[citation needed]

Being on the maritime route between China and South India, the Malay peninsula was involved in this trade The Bujang Valley, being strategically located at the northwest entrance of the Strait of Malacca as well as facing the Bay of Bengal, was continuously frequented by Chinese and south Indian traders. Such was proven by the discovery of trade ceramics, sculptures, inscriptions and monuments dated from the 5th to 14th century.[citation needed]

In Kedah, there are remains showing Buddhist and Hindu influences which have been known for about a century from the discoveries reported by Col. Low and has recently been subjected to a fairly exhaustive investigation by Quaritch Wales. Wales investigated no fewer than 30 sites around Kedah.[53]

An inscribed stone bar, rectangular in shape, bears the ye-dharmma formula in the Pallava script of the 7th century, thus proclaiming the Buddhist character of the shrine, of which only the basement survives. It is inscribed on three faces in the Pallava script of the 6th century, possibly earlier.[citation needed]

Srivijaya (7th–13th century)[edit]

Between the 7th and the 13th century, much of the Malay peninsula was under the Buddhist Srivijaya empire. The site Prasasti Hujung Langit, which sat at the centre of Srivijaya's empire, is thought to be at a river mouth in eastern Sumatra, based near what is now Palembang, Indonesia.[54] For over six centuries the Maharajahs of Srivijaya ruled a maritime empire that became the main power in the archipelago. The empire was based around trade, with local kings (dhatus or community leaders) that swore allegiance to a lord for mutual profit.[55] In 1025, the Chola dynasty captured Palembang, the king and all members of his family, including courtiers and took all his wealth; by the end of the 12th century Srivijaya had been reduced to a kingdom, with the last ruler in 1288, Queen Sekerummong who had been conquered was overthrown by four pious people which became a milestone in the establishment of the Kingdom of Sekala Brak in Gedung Dalom Batu Brak, Liwa, West Lampung Regency which was based on Islamic religious values on 29 Rajab 688 AH. Majapahit, a subordinate to Srivijaya, soon dominated the regional political scene.[56]

Relations with the Chola empire[edit]

The relation between Srivijaya and the Chola Empire of south India was friendly during the reign of Raja Raja Chola I but during the reign of Rajendra Chola I the Chola Empire invaded Srivijaya cities (see Chola invasion of Srivijaya).[57] In 1025 and 1026, Gangga Negara was attacked by Rajendra Chola I of the Chola Empire, the Tamil emperor who is now thought to have laid Kota Gelanggi to waste. Kedah (known as Kadaram in Tamil) was invaded by the Cholas in 1025. A second invasion was led by Virarajendra Chola of the Chola dynasty who conquered Kedah in the late 11th century.[58] The senior Chola's successor, Vira Rajendra Chola, had to put down a Kedah rebellion to overthrow other invaders. The coming of the Chola reduced the majesty of Srivijaya, which had exerted influence over Kedah, Pattani and as far as Ligor. During the reign of Kulothunga Chola I, Chola overlordship was established over the Srivijaya province Kedah in the late 11th century.[59] The expedition of the Chola Emperors had such a great impression on the Malay people of the medieval period that their name was mentioned in the corrupted form as Raja Chulan in the medieval Malay chronicle Sejarah Melaya.[60][61][62] Even today, the Chola rule is remembered in Malaysia as many Malaysian princes have names ending with Cholan or Chulan, one such was the Raja of Perak called Raja Chulan.[63][64]

Pattinapalai, a Tamil poem of the 2nd century AD, describes goods from Kedaram heaped in the broad streets of the Chola capital. A 7th-century Indian drama, Kaumudhimahotsva, refers to Kedah as Kataha-Nagari. The Agni purana also mentions a territory known as Anda-Kataha with one of its boundaries delineated by a peak, which scholars believe is Gunung Jerai. Stories from the Katasaritasagaram describe the elegance of life in Kataha. The Buddhist kingdom of Ligor took control of Kedah shortly after. Its king Chandrabhanu used it as a base to attack Sri Lanka in the 11th century and ruled the northern parts, an event noted in a stone inscription in Nagapattinum in Tamil Nadu and the Sri Lankan chronicles, Mahavamsa.[citation needed]

Decline and breakup of Srivijaya

At times, the Khmer Kingdom, the Siamese Kingdom, and even Cholas Kingdom tried to exert control over the smaller Malay states.[41] The power of Srivijaya declined from the 12th century as the relationship between the capital and its vassals broke down. Wars with the Javanese caused it to request assistance from China, and wars with Indian states are also suspected. In the 11th century, the centre of power shifted to Malayu, a port possibly located further up the Sumatran coast near the Jambi River.[55] The power of the Buddhist Maharajas was further undermined by the spread of Islam. Areas which were converted to Islam early, such as Aceh, broke away from Srivijaya's control. By the late 13th century, the Siamese kings of Sukhothai had brought most of Malaya under their rule. In the 14th century, the Hindu Majapahit Empire came into possession of the peninsula.[54]

An excavation by Tom Harrisson in 1949 unearthed a series of Chinese ceramics at Santubong (near Kuching) that date to the Tang and Song dynasties. It is possible that Santubong was an important seaport in Sarawak during the period, but its importance declined during the Yuan dynasty, and the port was deserted during the Ming dynasty.[65] Other archaeological sites in Sarawak can be found inside the Kapit, Song, Serian and Bau districts of Sarawak.[66]

According to the Malay Annals, a new ruler named Sang Sapurba was promoted as the new paramount of the Srivijayan mandala. It was said that after he acceded to Seguntang Hill with his two younger brothers, Sang Sapurba entered into a sacred covenant with Demang Lebar Daun, the native ruler of Palembang.[67] The newly installed sovereign afterwards descended from the hill of Seguntang into the great plain of the Musi River, where he married Wan Sendari, the daughter of the local chief, Demang Lebar Daun. Sang Sapurba was said to have reigned in Minangkabau lands.

In 1324, a Srivijaya prince, Sang Nila Utama founded the Kingdom of Singapura (Temasek). According to tradition, he was related to Sang Sapurba. He maintained control over Temasek for 48 years. He was recognized as ruler over Temasek by an envoy of the Chinese Emperor sometime around 1366. He was succeeded by his son Paduka Sri Pekerma Wira Diraja (1372–1386) and grandson, Paduka Seri Rana Wira Kerma (1386–1399). In 1401, the last ruler, Paduka Sri Maharaja Parameswara, was expelled from Temasek by forces from Majapahit or Ayutthaya. He later headed north and founded the Sultanate of Malacca in 1402.[68]: 245–246 The Sultanate of Malacca succeeded the Srivijaya Empire as a Malay political entity in the archipelago.[69][70]

Rise of Muslim states[edit]

Islam came to the Malay Archipelago through the Arab and Indian traders in the 13th century, ending the age of Hinduism and Buddhism.[71] It arrived in the region gradually and became the religion of the elite before it spread to the commoners. The syncretic form of Islam in Malaysia was influenced by previous religions and was originally not orthodox.[41]

Malaccan Sultanate[edit]

Establishment[edit]

The port of Malacca on the west coast of the Malay Peninsula was founded in 1400 by Parameswara, a Srivijayan prince fleeing Temasek (now Singapore),[41] Parameswara in particular sailed to Temasek to escape persecution. There he came under the protection of Temagi, a Malay chief from Patani who was appointed by the king of Siam as regent of Temasek. Within a few days, Parameswara killed Temagi and appointed himself regent. Some five years later he had to leave Temasek, due to threats from Siam. During this period, a Javanese fleet from Majapahit attacked Temasek.[citation needed]

Parameswara headed north to find a new settlement. At Muar, Parameswara considered siting his new kingdom at either Biawak Busuk or Kota Buruk. Finding that the Muar location was not suitable, he continued his journey northwards. Along the way, he reportedly visited Sening Ujong (former name of present-day Sungai Ujong) before reaching a fishing village at the mouth of the Bertam River (former name of the Melaka River) and founded what would become the Malacca Sultanate. Over time this developed into modern-day Malacca Town. According to the Malay Annals, here Parameswara saw a mouse deer outwitting a dog resting under a Malacca tree. Taking this as a good omen, he decided to establish a kingdom called Malacca. He built and improved facilities for trade. The Malacca Sultanate is commonly considered the first independent state in the peninsula.[72]

In 1404, the first official Chinese trade envoy led by Admiral Yin Qing arrived in Malacca. Later, Parameswara was escorted by Zheng He and other envoys on his successful visits. Malacca's relationships with Ming granted protection to Malacca against attacks from Siam and Majapahit and Malacca officially submitted as a protectorate of Ming China. This encouraged the development of Malacca into a major trade settlement on the trade route between China and India, the Middle East, Africa and Europe.[74] To prevent the Malaccan empire from falling to the Siamese and Majapahit, he forged a relationship with the Ming dynasty of China for protection.[75][76] Following the establishment of this relationship, the prosperity of the Malacca entrepôt was then recorded by the first Chinese visitor, Ma Huan, who travelled together with Admiral Zheng He.[77][73] In Malacca during the early 15th century, Ming China actively sought to develop a commercial hub and a base of operation for their treasure voyages into the Indian Ocean.[78] Malacca had been a relatively insignificant region, not even qualifying as a polity prior to the voyages according to both Ma Huan and Fei Xin, and was a vassal region of Siam.[78] In 1405, the Ming court dispatched Admiral Zheng He with a stone tablet enfeoffing the Western Mountain of Malacca as well as an imperial order elevating the status of the port to a country.[78] The Chinese also established a government depot (官廠) as a fortified cantonment for their soldiers.[78] Ma Huan reported that Siam did not dare to invade Malacca thereafter.[78] The rulers of Malacca, such as Parameswara in 1411, would pay tribute to the Chinese emperor in person.[78]

The emperor of Ming dynasty China was sending out fleets of ships to expand trade. Admiral Zheng He called at Malacca and brought Parameswara with him on his return to China, a recognition of his position as the legitimate ruler of Malacca. In exchange for regular tribute, the Chinese emperor offered Melaka protection from the constant threat of a Siamese attack. Because of its strategic location, Malacca was an important stopping point for Zheng He's fleet.[79] Due to Chinese involvement, Malacca had grown as a key alternative to other important and established ports.[a] The Chinese and Indians who settled in the Malay Peninsula before and during this period are the ancestors of today's Baba-Nyonya and Chitty communities. According to one theory, Parameswara became a Muslim when he married a Princess of Pasai and he took the fashionable Persian title "Shah", calling himself Iskandar Shah.[76] Chinese chronicles mention that in 1414, the son of the first ruler of Malacca visited the Ming emperor to inform them that his father had died. Parameswara's son was then officially recognised as the second ruler of Melaka by the Chinese Emperor and styled Raja Sri Rama Vikrama, Raja of Parameswara of Temasek and Malacca and he was known to his Muslim subjects as Sultan Sri Iskandar Zulkarnain Shah (Megat Iskandar Shah). He ruled Malacca from 1414 to 1424.[80] Through the influence of Indian Muslims and, to a lesser extent, Hui people from China, Islam became increasingly common during the 15th century.

Rise of Malacca

After an initial period paying tribute to the Ayutthaya,[41] the kingdom rapidly assumed the place previously held by Srivijaya, establishing independent relations with China, and exploiting its position dominating the Straits to control the China-India maritime trade, which became increasingly important when the Mongol conquests closed the overland route between China and the west.

Within a few years of its establishment, Malacca officially adopted Islam. Parameswara became a Muslim, and because Malacca was under a Muslim prince, the conversion of Malays to Islam accelerated in the 15th century.[54] The political power of the Malacca Sultanate helped Islam's rapid spread through the archipelago. Malacca was an important commercial centre during this time, attracting trade from around the region.[54] By the start of the 16th century, with the Malacca Sultanate in the Malay peninsula and parts of Sumatra,[81] the Demak Sultanate in Java,[82] and other kingdoms around the Malay archipelago increasingly converting to Islam,[83] it had become the dominant religion among Malays, and reached as far as the modern-day Philippines, leaving Bali as an isolated outpost of Hinduism today. The government in Malacca was based on the feudal system.[84]

Malacca's reign lasted little more than a century, but during this time became the established centre of Malay culture. Most future Malay states originated from this period.[71] Malacca became a cultural centre, creating the matrix of the modern Malay culture: a blend of indigenous Malay and imported Indian, Chinese and Islamic elements. Malacca's fashions in literature, art, music, dance and dress, and the ornate titles of its royal court, came to be seen as the standard for all ethnic Malays. The court of Malacca also gave great prestige to the Malay language, which had originally evolved in Sumatra and been brought to Malacca at the time of its foundation. In time Malay came to be the official language of all the Malaysian states, although local languages survived in many places. After the fall of Malacca, the Sultanate of Brunei became the major centre of Islam.[85][86]

16th–17th century politics in Malaya[edit]