Cánh Tả gốc Việt - CT ĐẶC BIỆT:

https://youtu.be/MN9ZXdgsNAM

Chữ "cánh tả" được hiểu là "thiên cộng" = có khuynh hướng nghiêng về cộng sản. Thiên tả còn có nghĩa "nghiêng về chủ nghĩa xạ hội" mà chủ nghĩa xã hội cũng là cộng sản nhưng tránh né chữ 'cộng sản", một thứ đi vòng vo, úp mở về thiên cộng, thân cộng.

Một chuyến đi khá vất vã

Chuyện cuộc tranh cử của anh Hùng Cao

https://youtu.be/YfifY5jpu2w

Biểu lộ cảm Tình về ngày 30.4 ở Canberra của người Úc gốc Việt.

https://youtu.be/YnvbVz46kyU

Biểu lộ cảm Tình về ngày 30.4 ở Canberra của người Úc gốc Việt

https://youtu.be/DIWWQQvxlCk

Đi Canberra dạy con lịch sử Việt.

https://youtu.be/p3ZccijAORA

30-4-2022 TAN GAU THU BAY

https://youtu.be/ah4Vh8ABKa0

Lễ tưởng niệm tháng tư đen tại Atlanta

https://youtu.be/gpHrFV-K__0

CHƯƠNG TRÌNH ĐẶC BIỆT: Tưởng niệm 47 năm tháng 4 đen 30/4/1975 - 30/4/2022

https://youtu.be/b5tkfoBqCRg

Đại lộ đẫm máu! Tôi đứa bé 9 tuổi là người chứng nhân của lịch sử

https://youtu.be/ebv5ZNtGhqI

CÁNH TAY NỐI DÀI của Viêt cộng nằm trong truyền thông hải ngoại http://nguyenvanguyen.blogspot.com/2018/09/canh-tay-noi-dai-cua-viet-cong-nam.html

CÁNH TAY NỐI DÀI của Việt cộng nằm trong truyền thông hải ngoại

Is that a wise choice?

Ad by Lighthouse Life Direct

Lucia Millar

, Quran user at Quora (2020-present)

Updated Nov 26

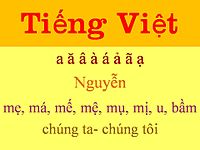

Question: Why does Vietnam use the Latin alphabet in its writing system?

Answer: The Latin alphabet with the Vietnamese Quoc Ngu script has helped the Vietnamese for ending Illiteracy most of the Vietnamese after regaining independence in 1945. Albeit suffering a century of the French colonial brutal rule and putting the anti-French sentiment aside, the Vietnamese are still brave enough to choose what benefits them, and choosing the Latin script is a practical and rational option. The Vietnamese language has been recorded in the Latin script has made the Vietnamese easier to learn, easier to write, to read. Your question is that Is choosing the Latin script a wise choice? From my point of view, It is not only a wise choice but also a brave one as follows:

Firstly, anti-French sentiment, as well as anti-western sentiment, had risen sharply in Vietnam after 1945, most of the Vietnamese nation stood up and fought against the French re-conquest war from 1945–1955. There were a certainly large amount of the Vietnamese people who hated the French colonists and the French colonial legacy to the bone. So, at that time, choosing the Chu Quoc Ngu script as one of the French colonial legacies was a brave choice for any of the Vietnamese leaders instead of their own ineffective/unpopular script - the Han Nom script.

The Han-Nom script of Vietnam

Removing the outdated Han Nom script and adopting the modern script - the Chu Quoc Ngu is also an important part of the Vietnamese revolutionary that has nothing to do with the Anti-Chinese sentiment.

Chu Quoc Ngu script

Secondly, The Chu Quoc Ngu has not only inherited the strengths of the Chu Han Nom but also resolved most of the problems of the Chu Han Nom script before that the Vietnamese ancestors had failed to reform.

After thousands of years of establishing the country, the development of the Chu Quoc Ngu as it is today is one of the greatest achievements of the Vietnamese nation. It is the first time in Vietnamese history that they have their writing language different from the rest of the world and recorded exactly their mother tongue even though they have to borrow many things from the western civilization.

P/s: Unlike the Chinese language, the Vietnamese language has not met much the homonym problems when using the Chu Quoc Ngu based on the Latin Alphabet because of differences of tones.

Lucia Millar

Tran Binh Ngoc · July 26, 2021

Totally agree about homonym problems in Chinese language. Chinese is actually very hard to learn because of that.

Tuấn Anh Lê · July 6, 2021

I am Vietnamese, I think Vietnamese people should probably live for their own sake rather than the country. Confucianism and Chinese characters both disappeared. Vietnam has nothing left. Culture is broken

Lucia Millar · July 6, 2021

How the culture of Vietnam is broken?

Confucianism is just a philosophy - It will never disappear if you still read it and appreciate it.

The Chinese Han characters has never been banned from learning it studying and you could search for them, How it become disappeared?

Lucia Millar.

Tu Le Hong · July 12, 2021

We should review the history to see whether the Vietnamese culture is broken because of switching from Chinese characters. In the Hung Vuong era, the Vietnamese used to have our own scripting system - which is called Khoa Đẩu. Even Chinese history books mention this. After the Trung sisters fell and the Chinese invaded our country, what did they do? They destroyed all objects with our characters on them, killed all our literate people, and forced the others to use Chinese script. They attempted to turn Vietnamese into Chinese. Ironically, it is adopting Chinese characters that broke our culture. Adopting Chinese characters is actually more like national disgrace than pride. Our ancestors did create valuable masterpieces in Chinese, but what make them masterpieces is their content, not the Chinese characters themselves. We appreciate our ancestor heritage, but we also never forget the disgrace of losing our country and our ancient scripting system. If our ancestors had a choice, they would not choose the Chinese scripting system. In fact, switching away from Chinese characters is a part of the effort to restore our cultural values. Chinese was a foreign language for the Vietnamese from the beginning, and nowadays we return it back to the position of a foreign language. And about Confucianism, that philosophy originated from China, not Vietnam, so it is not our ancestor heritage. The adoption of Confucianism was even a backward move for the Vietnamese. Before the rule of China, Vietnamese women had more rights. As you can see, Trung sisters could be emperor. After the Chinese forced Confucianism into Vietnam, women rights were gone.

Andrew Chang · November 5

I think you guys go too far back. Even modern Chinese is very different from when the Trung sisters were still alive. Everyone has moved on and so should all of you. Be proud of your own culture regardless of where it has originated from because you have put in your own mark and made it yours. We are continuously creating culture as we move forward into the future.

Minh Tran · November 19

A problem of today’s people is that they project their own 21st century thinking and perceptions to ancient era, and expect people of the ancient past to live, speak, think and even look like they do today. 2,000 years ago at the end of the Bronze Age, there were only a few advanced civilisations in the world. As we know, the prominent were Chinese in the East, Indian in the subcontinent, Greco-Roman in Europe. These civilisations developed relatively high culture, state governance, societal structure, written scripts, architecture, and of course warfare technology and army to conquer neighbouring lands.

The rest of the world were tribal people, progressing from slash-burn cultivation to early forms of settlement and agriculture. They were around 1,000 years behind in development compared to the Chinese, the Indians, the Greco-Romans. It was therefore natural for ancient tribal people to be absorbed into a higher civilisation, either through conquest or through adaptation.

Vietnam follows the Chinese culture while they dominate us. Their neighbours Thailand, Laos and Cambodia adapt the Indic culture.

Why didn’t Vietnam, Thailand, Laos and Cambodia invent their own culture? Why should they? Or could they?

If Vietnam hadn’t been occupied by China, what would have happened to Vietnamese culture. There were 3 choices:

- Chinese, or Indic

- A Vietnamese distinct culture, separate from Chinese and Indic.

- The third choice is extremely unlikely.

No country in East Asia, South Asia and South East Asia could manage to do that, as they were so so far behind the Chinese and Indians in the ancient time. Vietnam was no difference. Japan and Korea adapted Chinese culture by choice, not by force by the way.

As to “Khoa Dau”, the so-called Vietnamese ancient scripts, there is no archeological evidence. Some wiggly figures that anyone could scrawl, if existing, can’t be called a written script by any figment of imagination.

In short, hadn’t Vietnam belonged to Sinosphere, we would’ve belonged to Indosphere anyway, which could’ve possibly been the case had history been different. Our people would’ve used Sanskrit instead Chinese scripts.

Hải Phong Nguyễn · December 5

I don't think we should use Chinese view toward other civilization. In Chinese view, they are center of world, great civilization while all other is “man di". Our ancestors' civilization all destroyed by Chinese and they try sinicize all they can.

The problem of ancient Vietnam culture is not “it more advance or leave behind by china ancient culture", but Vietnam ancestors was conquested by China ancestors.

An example is Ming dynasty's 20 years occuption. All Vietnam culture was destroyed. That is what happens in only 20 years, what about 1000 years?

Minh Tran · December 5

My point is that if Vietnam was not conquered by China, which was a real historical possibility, Vietnam’s culture would be either Sinitic (like Korea, Japan) or Indic (like Thailand, Laos, Cambodia, Myanmar).

Japan wasn’t invaded by China. Korea wasn’t occupied by China except for a brief period.

Civilisation adaptation happens everyday. You and I are Vietnamese, writing and speaking English, typing on a laptop or a smart phone - a Western invention, wearing Western clothes, educated in a Western system. Our government and economic systems are copied from the West. The ancient people in Asia did the same thing too. They adapted their civilisations from either the Chinese or the Indians. There was nothing unusual or controversial about that. Those who did not adapt to a higher civilisation would remain backwards and would eventually disappear.

The Ming’s policy during its occupation of Vietnam in the 15th century was to destroy the Vietnamese books and cultural artifacts. But Vietnamese books were all written in Chinese scripts. Vietnamese temples were in Chinese styles. My point is, brutal as the Ming’s occupation was, its policy did not make any fundamental change to the fact that Vietnamese culture was and still is Sinitic.

In fact, the Le dynasty, after defeating the Ming, changed Vietnamese society to more Confucian and more Sinitic than the previous Vietnamese dynasties, Ly and Tran. When it comes to Sinicism, the Nguyen dynasty was the most ardent devotees in Vietnamese history. Did you know that in the Nguyen official records, Vietnamese Kinh people were classified as Hán people. Yes, Hán Nhân.

Thuy Nguyen · November 27

Because the conquerer Chinese forced our ancestors to use only Chinese characters, our ancestors had to invent Chữ Nôm as a kind of slang to keep our spoken language. It was only an improvised tool used under oppression. Now with free choice, we choose Chữ Quốc Ngữ as our most useful tool for writing. Why should we go back to use the improvide tool.

Profile photo for Thang Nguyen Thang Nguyen · October 24

I totally agree with Tu Le Hong, being moved out from China and situated right next to it we can not avoid to have some Chinese philosophy and cultural, but Vietnam still have their own culture as a whole: Look alike, do alike but still not the same.

Profile photo for Steve Christensen Steve Christensen · July 24, 2021

If anything Han Chinese culture was broken by the Cultural Revolution and the destruction of the four olds. Vietnam did not go through this self destruction but only in limited circumstances. They say the worst aspects of Chinese now come from the generation who grew up as the Red guards and their entitlement and selfish actions are apparent. Who is pushing in line at the Market? its that 65 year old woman who is the most rude.

Profile photo for Duy Trịnh Khắc Duy Trịnh Khắc · January 26

If you want to practice Confucianism or learning Chinese, you can do it, no one stop you. The Chinese characters is just a writing tool, how does a tool can break our culture when we don’t use it? And you might not realize but the words we are seeing on screen are encoded to binary number, which is understood by machine so they can decode to other screens. Does the way computers decode/encode words break our culture? If not, then what is the problem of using Latin script to write our language?

Again, writing system is just a tool to etch our verbal language to paper, stone, etc. Don’t make it to be something that without it, we are not us.

Comment deletedJuly 15, 2021 Nguyễn Nhật Hoang · September 29

I think it's a good choice.

Vietnam gained independence. If we use Chinese characters, many people will sometimes think we look like Chinese. On the other hand, using the letters of the alphabet and Vietnamese Quoc Ngu will make it easier for people to learn when the post-war conditions are very difficult and many Vietnamese people at that time did not know how to read and write.

Lucia Millar · September 29

Lucia Millar

Bryon Ye · November 10

So you change your culture to not look like another culture lol? That’s very sad… you think westerners can tell the difference just because you use Latin script… your very wrong. ahaha

Lucia Millar · November 26

This is your ignorance. Vietnam and the Vietnamese have used the current Latin script for it's usefulness, not because of what the westerners view Vietnam. The people may hate the French colonists but not anything relating to the French culture.

Profile photo for Adrion VII Adrion VII · July 9, 2021

Very curious why the first Vietnamese linguists chose

to use “Đ” instead of “D”,

and “D” instead of “Z”.

Lucia Millar · November 26

I believe the sound “D” is not the same Z even though they are very very similar. The ways to pronounce D and Z are different

Thang Nguyen · October 24

I admire our forefathers who invented those signs to add to the Latin alphabet to make them easier to learn to read and write. As you see; “Đ” and “D” Put in front of a vowel it pronounced different and become different meaning. As with the “Z” the sound is too lightly and we don’t have the words with that sound. Some people wrote “dz” together, but it’s not popular and it’s not teaching in literature.

Thuy Nguyen · November 27

The pronunciation is different for various locatilities. The writing was made such that all regions can use it with minimum ambiguity.

There is a simple guide for foreigners here.

The problems in making Vietnamese writing using Latin alphabet.

Every language has some peculiar parts and also can miss out totally some other parts. For examples, there are no strong r (French r) in English, while there are no English “th” consonant or Englis…

https://survivaltricks.wordpress.com/2021/11/13/the-problems-in-making-vietnamese-writing-using-latin-alphabet/?preview=true

and here

Pronunciation of Written Vietnamese in former RVN

Pronunciation of Written Vietnamese in former RVN by tonytran2015 (Melbourne, Australia). Click here for a full, up to date ORIGINAL ARTICLE and to help fighting the stealing of readers’ traffi…

https://survivaltricks.wordpress.com/2019/04/10/pronunciation-of-written-vietnamese-in-former-rvn/

Tu Le Hong · July 22, 2021

The ‘đ’ and ‘d’ do not seem reasonable nowadays, but in the past they made some sense. Nowadays, ‘đ’ is pronounced like ‘d’ in English, but it used to be pronounced differently. ‘d’ and ‘gi’ was used to denote similar but distinct sounds. ‘gi’ is a diphthong denoting a fricative sound like ‘z’ in English, but ‘gi’ was chosen probably due to the influence from the Portuguese language. It is too late to change ‘đ’ to ‘d’ and ‘d’ to ‘z’ now because there are already too many books with ‘đ’ and ‘d’. We just have to keep living with them. I believe that other languages also have many vestiges of the past, and they cannot be changed for the same reason.

Duong Thanh Son · July 15, 2021

Because the old Vietnamese has many different tones, so it changed as a different sign in writing.

Profile photo for John Vu John Vu · October 25

Portugee's father created Latin Alphabet for Việt Nam with the main objective. To promote Catholicism in Vietnam. Later on, it became National Languages. Vietnam is the only Asian Country on this planet that has used Latin Alphabet.

Lucia Millar · November 26

Indonesia also used the Latin version.

Thuy Nguyen · November 27

There is nothing wrong with Latin alphabet which descended from Egyptian alphabet and has now produced the International Phonetic Symbols.

What is wrong with using Latin alphabet or International Phonetic Symbols?

Hùng Hoàng Văn · July 18, 2021

In my view, using “Chữ quốc ngữ” is just wise-choice. No Vietnamese hates French, English or Chinese language (particularly, scripts of these languages), though these nations were enemies to Vietnamese nation some time. And more, Latin alphabet of Vietnamese language is not legacy of French colonials. “Chữ quốc ngữ” was created by a Portuguese missioner approximately in sixteen century.

“Chữ quốc ngữ” became popular after 1906 King Thanh Thai's program included a program to teach The National Language, Vietnamese school educators supported the spread of Latin as a means to open the people's mind, concussion of the people spirit and people living

Khai dân trí

Chấn dân khí

Hậu dân sinh

“Chữ quốc ngữ” for the reason it is easy to learn, to read and to write for all Vietnamese.

Thuy Nguyen · November 27

Chữ Quốc Ngữ is the best tool to describe Vietnamese pronunciation.

I challenge users of Chữ Nôm to write

“Rừng rậm réo rắt”

in Chữ Nôm so that other users of Chữ Nôm can read it back accurately.

On the other hand, all users of Chữ Quốc Ngữ can easily read it back accurately.

Thuy Nguyen · November 5

Vietnamese language is as different from Chinese language as English from French.

You can use English to teach people to speak French but that is a horrible task. So using Chinese characters to teach people to speak Vietnamese is also that horrible. Chữ Nôm is such an attempt.

Profile photo for Lê Quang Huy Lê Quang Huy · August 3

In fact, Vietnamese is different from Chinese because it is rich in vowels and consonants, not in tones.

Lucia Millar · August 3

Yeah, It is one of the main reason why China failed to assimilate the Vietnamese.

Lê Quang Huy · August 3

It's like the moon hitting the Earth. the moon carries part of the earth's matter and the earth bears part of the moon's matter, but the earth is still the earth and the moon is still the moon. It has a large impact force, but it is not one-way. The nature of this collision is due to gravity. I don't know if groups of people in Guangdong and Fujian with other languages have been assimilated. They still have a lot of personality.

However, most of the people in Guangdong and Guangxi have considered themself as the Chinese Han people, not Viet/Yue people anymore.

Quoc-Thai Ngo · July 7, 2021

You are absolutely right, it’s a real brave and patriotic choice of real leaders. These leaders, belonging likely to an elite and privilege class, abolish their own privilege as the only literates of people! It is far more confortable for them to keep their privilege. Hope our current leaders follow this beautifull example. The people first!!!!

Profile photo for P Hunter P Hunter · November 30

I personally think the Han Nom script would have been a better choice. Although it was uneffective/unpopular, it bothers me that we chose westerners script over one used for so long. My ideology is that it could have been improved, and the great thinkers in Vietnam at that time would help improve and eventually find solutions for what made it ineffective. I understand that it was easier but it would make us more unique if we didn't conform to western script. Of course this is just my opinion and you are free to disagree!

David Doan · July 15, 2021

In the early 1970s as a 5,6 year old kid, I lived in the predominantly Chinese district of Saigon. I remembered a Chinese kid in my neighbourhood of about the same age used to practice everyday writing Chinese scripts. I am so glad now I did not have to do that. I am also glad that my ancestors were forced to sever completely the Chinese scripts, otherwise we would be in the same situation as the Korean and Japanese. They have a Latin alphabet writing system but it’s never widely used because it’s not compulsory. As you have already mentioned, the new chữ Quốc Ngữ is easy to learn, easy to write especially if you can touch-typed on the computer. Initially there was resistance and resentment by the “elites” for obvious reasons but the new system was quickly adopted by the population because a) it’s compulsory, b) open to anyone even the poor peasant kids from the village, c) job opportunity and highly paid too.

Dương Dương · October 9

Seemingly, not all people in Vietnam got any issues in term of learning Chinese. You know it’s just merely a merit to get any understand of other literacy of languages or cultures. But the problem here is the CCP policies and to some certain kind of Chineses people’s perspective that kind obsoleted or right-winger. As long as Vietnam still shares the same border, and leans extensively on the China’s gov and economic, certainly, under any circumstances in either short or long term. The conflicts surely persist, people have a hold of negative prejudice for China withal. For the past have proved, China tyrants love conquered, they just pick their sword and their go. Fair enough!

Profile photo for Lucia Millar Profile photo for Nguyen Vinh Phuc Nguyen Vinh Phuc · July 15, 2021

the chu quoc ngu is a the biggest historic blessing for the people of Viet Nam The vietnamese is intelligent and chu quoc ngu help this people developing very quickly ; this development is gigantesque

Shaun Darragh · October 23

Lusia, as usual your English is Impeccable. One minor correction. where you state that “Quoc Ngu" script has helped the Vietnamese for ending illiterate… I believe you meant to say …Illiteracy. Glad to see you’re still fighting the good fight.

Lucia Millar · July 5, 2021

The Chu Quoc Ngu is a Vietnamese proper name. You could not use Google Translate in this case.

Sở Quốc (So Quoc) is the Sino- Vietnamese name for the State of Chu. Of course, Nước Sở is also the native Vietnamese name for the State of Chu.

Lusia Millar. Profile photo for Minh Tran Minh Tran · July 5, 2021

Hi, my 2 cents are below.

Chữ: Vietnamese for Alphabet, Word

Quốc Ngữ: Sino-Vietnamese 國語 for National Language

Profile photo for Lucia Millar Lucia Millar · July 5, 2021

He has used Translate tool to translate “Chu Quoc Ngu” and it turns into “State of Chu”.

Nguyen Hung · July 9, 2021

Vietnamese grammar and Chinese grammar are different. Quoc Ngu is noun-adjective and Chu is noun.

Profile photo for Thuy Nguyen Thuy Nguyen · November 27 No.

Ngu was a Dynasty old Viet, set up by the Đế “Thuấn”.

From Tam Hoàng, Ngũ Đế.

Ngũ Đế:

1. Nghiêu of Đường Dynasty,

2.Thuấn of Ngu Dynasty,

3. Ân of Hạ Dynasty,

4. Vũ (who drained the land) of Hạ Dynasty,

5. Châu Văn Vương of Châu Dynasty.

On the other hand, Chữ Quốc Ngữ means Writing for National (Spoken) Language.

Trần Thảo Nguyên (陈草元-Thao Chan) · November 26

Before the French came to Annam (Vietnam today), we did use Hanzi (chinese characters, which we call Chữ Nho) as our writing system, which can be found in our old books.

Due to the trouble of communicating, some priests at that time use Latin word to write down how Annamese pronounce each by each word. That creates what today we call Chữ quốc ngữ(vietnamese current writing system).

Vietnamese are speaking one kind of old Chinese language but written in Latin alphabet, which is another form of Pinyin. And if Vietnamese do not learn Chinese, the original word, they will not understand the correct meaning of that word, which leads to a tragic fact today many words are misunderstood by young people .

however, the current wave of anti China and pro western culture makes it hard for Vietnamese to realize they need to bring the teaching of Chinese language to school, many hates everything relating to China, and do not know that 80–90% of vietnamese words have origin from Chinese words. A large number of Vietnamese also have Chinese origin too.

its time to change and go back to our culture, which is the key factor to make one country healthy and develope.

Profile photo for Lucia Millar Lucia Millar · November 26

The Han-Nom script is outdated and failed product compared to the current Vietnamese script.

Lucia Millar. Profile photo for Trần Thảo Nguyên (陈草元-Thao Chan) Trần Thảo Nguyên (陈草元-Thao Chan) · November 26

Haha your idea then, i do not think so. I am a Vietnamese too, have been learning chinese for 4 years now and found that a gross deal of daily use Vietnamese have origin from very old chinese words. What i want to say here is, many Vietnamese written in latin have different meanings but same pronunciation, one would not be able to understand it if not learning the root word, which, clearly is a word written in Hanzi, Chinese character.

Profile photo for Lucia Millar Lucia Millar · November 27

Thank you for your share.

It is a matter of opinion. If the Han-Nom script is successful, It should be used as the official script of Vietnam now. You could agree to disagree.

I am Vietnamese too, have been learning Chinese for 4 years now and found that a gross deal of daily use Vietnamese have origin from very old Chinese words.

Comment 1: This is your view however, 30–40%/70% of the Vietnamese vocabularies are borrowing words from the Middle Chinese language. You are Vietnamese or not the Vietnamese is not really important.

What I want to say here is, many Vietnamese written in Latin have different meanings but the same pronunciation, one would not be able to understand it if not learning the root word, which, clearly is a word written in Hanzi, Chinese character.

Comment 2: It is not a matter of not learning the root word but learning the meaning of the Vietnamese words. Learning the Vietnamese vocabulary means learning how to write, how to read, how to use including what these vocabularies mean. In the end, It is a matter of many Vietnamese people who are not interesting in learning the meanings of their vocabularies.

Do you really understand the concept of the Han-Viet words?

Lusia Millar Profile photo for Hải Phong Nguyễn Hải Phong Nguyễn · December 5

Between “write a word and know some of it's use" and learn “how to write many words with different means but same pronunce"

We often talk to other, not write to. We have more thing to care about than what meaning of a word.

A word often don't stand lonely but with other words in a sentence => we can understand it meaning base on sentence. If someone don't even care to know a meaning of word, how you think they will want to learn and remember to write a new word with same pronunce but different meaning.

Duy Trịnh Khắc · January 26

I am not sure about the “brave” one. I thought it was just a historical progress, when at the time, Han Nom was really outdated when people who can read books were mostly taught by French. The government staffs were more familiar with Latin script. And the usage of Chu Quoc Ngu was wide spread. I thought it was an obvious choice.

Profile photo for Trần Thảo Nguyên (陈草元-Thao Chan) Trần Thảo Nguyên (陈草元-Thao Chan) · November 26

“Removing the outdated Han Nom script and adopting the modern script - the Chu Quoc Ngu is also an important part of the Vietnamese revolutionary that has nothing to do with the Anti-Chinese sentiment. “.

This is a dangerous thing to say, language and culture is the crucial part of every country, removing Han Nom and Hanzi to use Chu quoc ngu is the needs at that time to erase illiteracy. But same like Pinyin, Vietnamese are speaking one kind of language where they do not understand the meaning of the word if do not look it up in the Han Nom dictionary . This is a fact whether you admit it or not.

Lucia Millar · November 26

But same like Pinyin, Vietnamese are speaking one kind of language where they do not understand the meaning of the word if do not look it up in the Han Nom dictionary. This is a fact whether you admit it or not.

Comment: You are not the Vietnamese but the Chinese. The Vietnamese current script is very different from the Chinese Pinyin. I see the problems of the Chinese Pinyin script but these problems are not related to the Vietnamese national script. However, You should not use your problems of the Chinese Pinyin to consider the Vietnamese Latin script.

Lucia Millar.

Profile photo for Trần Thảo Nguyên (陈草元-Thao Chan) Trần Thảo Nguyên (陈草元-Thao Chan) · November 26

do not be blind by the hate for China government and bring that hate to everywhere and everything relating to china, they are a great culture in the shape of a country, and have alot of things for us to learn. Haters gonna hate. 80–90% of vietnamese words have origin from Chinese words, which we call Chu Nho, thats where our basement lie, where contains our culture, stop spreading this lie, this is very dangerous for Vietnam if they do not realize this.

Profile photo for Lucia Millar Lucia Millar · November 26

And this your message? I am thinking that you are wiser than Mr. Ho Chi Minh who chosen the current Latin script as the Vietnamese national script?

Lusia Millar.

Profile photo for Trần Thảo Nguyên (陈草元-Thao Chan)

Trần Thảo Nguyên (陈草元-Thao Chan)

· November 26

Please read again my comment, i did not say that using Chu quoc ngu is a wrong choice at that time by President Ho Chi Minh, the main purpose was to erase illiteracy. But these days we need to consider again the needs to learn Chu Nho again, that’s to help Vietnamese understand what they are speaking, really know what we are speaking, I hope you get my point here

Profile photo for Lucia Millar

Lucia Millar

· November 27

Thank you for your share. You mean that the Vietnamese people should learn the Han-Nom script to understand what they are speaking and really know what they are speaking.

I believe that they focus on learning the meaning of the Vietnamese vocabulary, they will definitely understand what they are speaking. Learning the old script: Han-Nom script is good to preserve the Vietnamese ancient script but for understand what the Vietnamese are speaking is quite unnecessary. The current script of Vietnam definitely helps the Vietnamese to learn the meanings of their vocabularies if they are interested in learning. It is a matter of the educational level of each people, not really relating to not learning the Han-Nom script at all.

Lusia Millar Profile photo for Hải Phong Nguyễn Hải Phong Nguyễn · December 5

The script from beginning is a tool to keep and transfer infomation, knowledge to later generation.

A good script should be a script which suitable with language, easy to learn and use.

Among Latin-Vietnamese script, Nôm script, and Chinese script, it's easy to know that Latin Vietnamese script is the most suitable, and easiest to learn and use.

Script is a tool for everyone, not a toy for top class person.

How long a Vietnamese to learn and read Latin Vietnamese script to read and write fluently? 1 2 year

How long for Nom. 5 10 year?

And how long for Chinese script? 5 10 year?

Profile photo for Trần Thảo Nguyên (陈草元-Thao Chan) Trần Thảo Nguyên (陈草元-Thao Chan) · December 5

“it's easy to know that Latin Vietnamese script is the most suitable, and easiest to learn and use.” i did not deny the fact that latin Vietnamese is easiest to learn and use, you can read again my comment above and everywhere. My point is if Vietnamese only learn the Latin script Vietnamese without learning the root word in Hanzi(chữ Nho), after few generations we will not understand what we are saying anymore cause you do not even know what that word really means. The message that what I’m trying to deliver here is not so hard for some people to understand, latin Vietnamese is one kind of “chữ phiên âm” from “chữ Nho” into “latin script”, and by using only the latin words like what Vietnam is doing now, you would forget what is the root word of that latin script, which is the true carrier of meaning that one word should have with it, the latin script just delivers the sound of that word only, which also means we are some kind of parrots that can speak but do not understand what we are speaking! Does it make sense to you now?

I’m not surprised when reading this news, the next generations will be more worse off than this if no one realize the fact that most of most Vietnamese now do not even understand anything of the books written by their ancestors. The breakdown of culture and history wave by getting rid of Chu Nho is a tragedy of Vietnam.

And may i ask again, why so many people here against anything relating to China even though it was also our heritage of our forefathers? We just share similarities with China does not mean that all of those similarities should be washed off completely, deny everything relating to them.

Lucia Millar · January 19

My point is if Vietnamese only learn the Latin script Vietnamese without learning the root word in Hanzi(chữ Nho), after a few generations we will not understand what we are saying anymore cause you do not even know what that word really means.

Comment: It is unnecessary to learn the Hanzi (Chữ Nho) to understand the Han-Viet words because many of the Han-Viet words have been changed in meanings and usages. Also, you could learn the meanings of the Han-Viet words through the Vietnamese Latin scripts. It is easier to learn and write except you are interested in learning the Han-Nom script.

Your points are interesting but unrealistic because it is not a matter of anti-China but conveniences and effectiveness of learning the Vietnamese Latin script far better than learning the Han-Nom script

Profile photo for 潼水北 潼水北

· November 8

You can say that Latin letters are modern in modern times, I have never thought.The Chinese input method system is currently very complete, and typing is not difficult or slow. In the cultural struggle with Westerners, Vietnam was the only East Asian nation that surrendered. You are not as good as South Korea. At least they are self-made Korean scripts. Your direct Latin scripts in Vietnam are a complete failure. Please stop pretending to be East Asia or Confucianism.

Profile photo for Lucia Millar Lucia Millar · November 26

There is such thing called cultural struggles between the western civilization and the eastern civilizations. If not, China should follow their tradition.

Profile photo for Hải Phong Nguyễn

Hải Phong Nguyễn · December 5

What is different between borrowed Chinese script and borrowed Latin script? If you call use latin script = surrender to western culture. Then you want us surrender to Chinese culture. What a good logic.

Script is not a toy, script is a tool. If you borrow a tool, tool which more suitable with you is the best tool. I will don't say Chinese script or latin is moderner, but more suitable.

Profile photo for Lucia Millar Lucia Millar

· January 19

They will not try to understand what you said. Your insisted view is that choosing the Latin script instead of the Han-Nom script means anti-China.

Royce Hong

· July 8, 2021

My answer is Yes, they have had a wise choice.

Chinese Han character will be gone naturally.

It will be useless in digital time near future.

Japanese too.

But, Latin, English, Korean will be main language.

You know what I mean?

So, Vietnam language will be survived I guess

Profile photo for Sean 김

Sean 김

· July 11, 2021

Great prediction. I see it too. English in the West and Hangul in the East in the Digital Era. You see it happening already America and Korea is leading the 4th industrial revolution and digital culture. Chinese script is obsolete in the Digital era as even the Chinese perfer to use Latin alphabetical script to type their of Hanja script.

Profile photo for Royce Hong

Lucia Millar · July 16, 2021

It is your Chinese problem, not the Vietnamese language matter.

Profile photo for Tianren Tan Tianren Tan

· November 2 https://impactotic.co/en/the-5-leading-countries-in-the-fourth-industrial-revolution-Colombia/

These Are The Six Countries Leading The Fourth Industrial Revolution - Blockhead Technologies

Profile photo for Peter Qian

Peter Qian

· January 18

I vote you two to be the greatest fortune tellers of 21st century, the wise man everyone in the world should bestow to!

Profile photo for Trần Thảo Nguyên (陈草元-Thao Chan) Trần Thảo Nguyên (陈草元-Thao Chan) · November 26 For example, 中英:zhongying: trung ương. Westerners will read that word zhongying, vietnamese read it trung ương, and it points to only one root chinese word 中英. Profile photo for Lucia Millar Lucia Millar · November 30 And?

Peter Qian

· January 18

China at one time was seriously considering adopting Pinyin as the written script to help alleviate illiteracy, that would have been a grave mistake as this will cutoff all future generations from the history, as well as creating untold confusion in many phrases having the same pronunciations! While it may help in initially gaining literacy, inevitably it will dumb down the whole population in literature and its sophistication. I do not know the Vietnamese language, but after reading the discussions here, I’ve some understanding now and can fully sympathize the struggle. Besides Chinese characters is a beautiful art that are so treasured in East Asia, and we will forever preserve it not as history relic but a heritage to live on. I heard Chinese is gaining popularity in Vietnam and I congratulate you of learning this art. I could just imagine the mother lode of your history you found while learning the written Chinese where the Latin script cannot!

BTW, the Catholic priests in Taiwan did for the same reason, creating a Latin script of Taiwanese(Min Nan dialect) to facilitate the spread of bible, the early Taiwan independence movement also tried to use the Latin Pinyin to make Chinese obsolete but there wasn’t much political support!

Profile photo for Lucia Millar

Profile photo for Trần Thảo Nguyên (陈草元-Thao Chan)

Profile photo for Lucia Millar

Lucia Millar

· January 19

Thank you for your share about the Chinese language but I do not think that Vietnam needs the comeback of the Han-Nom script at all. For ordinary people, Learning history does not need learning the old script.

Profile photo for Trần Thảo Nguyên (陈草元-Thao Chan)

Trần Thảo Nguyên (陈草元-Thao Chan)

· January 18

Finally, someone really understands what i wrote here. You are right, “I could just imagine the mother lode of your history you found while learning the written Chinese where the Latin script cannot!”, this is a gradual but soo interesting road to go. Before i learnt English, it took me 5 years to master this language. For Chinese, the time reduces half to 2.5 years due to the similarity. Btw, that’s a good luck for Taiwan to keep using Hanzi, language is the tool to retain culture of a group of people, no need to mention how important culture is. Hope Vietnam will soon find a way back to its fountainhead.

Profile photo for Peter Qian

Profile phot

o for Lucia Millar

Lucia Millar

· January 19

Actually, this is your personal experience and many of the Chinese will agree with your view because their media seems to support this view. However, changes of the Vietnamese script from the Han-Nom to the Latin is one of the greatest achievements of Vietnamese history. For the first time in Vietnam history, they have their full alphabets to record exactly their own languages and do not need to borrow the characters much from other languages.

In the end, I still respect your view and support your effort to learning the Vietnamese Han-Nom script to preserve partly the Vietnamese ancient culture.

Lusia Millar Sponsored by Natural Reviews

Why do seniors take collagen supplements?

Because they work! We recently listed the top five collagen brands.

Profile photo for Tu Le Hong Tu Le Hong , studied Computer Science at University of Economics, Ho Chi Minh City (2003) Answered Jan 22, 2021

Before the use of the Latin alphabet, Vietnam used to use Chinese script. The problem with Chinese script was designed for the Chinese language, not the Vietnamese language. The Vietnamese people were only forced to use it by the Chinese rulers. As the matter of fact, Chinese script does not have characters that describe things or concepts specific for Vietnam or Vietnamese.

Chinese script is simply not suitable for the Vietnamese language. Then it came Chữ Nôm, a scripting system based on the Chinese scripting system. As many have pointed out, Chữ Nôm was so awkward and burdensome, because it required the user to first master Chinese script, and then some more additional. It turns out that the Latin based script is most suitable for the Vietnamese language: It is phonetic, which means you do not have to learn too many characters to be literate. It is faster to learn. It can record all syllables of the Vietnamese language. I also has a useful side effect:

It makes it easier for Vietnamese to read words from European languages. In China or Japan, people do not generally read Latin-based scripts, to they have to translate foreign words to their respective language. But for Vietnamese it is much easier. Just throw in the word as it is and the Vietnamese can read it, although maybe not 100% accurately. For example, when a Vietnamese first see “El Niño”, she should be able to read it right away.

This makes it much easier for Vietnamese people to learn European languages. I personally love this “side effect.”

With regards to connection with the ancestry, there should be nothing to worry about. Some say that when you cannot read old scripts from you ancestors, it is a big problem. Well, even when you know Chinese characters, you many not understand what the old books say, because the same character may have a different meaning in the distant past. You need to learn a lot in order to understand them. It is normal for a modern person to unable to understand ancient script. This is common in the world actually. How many of the modern Englishmen can read old English script? How many of the modern Egyptians can read ancient Egypt script? If you want to understand the ancient script, just learn to read it.

The Latin-based script may not be perfect. We know that it still has some issues. However, it does not have to be perfect to work well. As the matter of fact, it works better than its predecessors. Therefore, the Latin script is a good choice for the Vietnamese language.

Thanh Tung , Business Manager (2016-present) Answered Jun 19, 2021

The benefits of Vietnamese are outstanding for us. Vietnamese is truly an enlightenment for Vietnam because:

1- Vietnamese is easy to learn, fast to learn, learners can read and write within 6 months. In a very short time after President Ho Chi Minh issued the order to erase blindness of writing, many Vietnamese people knew how to write.

2- Reflecting the full syllables of Vietnamese people, very easy to pronounce, very easy to spell, so there is no need to remember words.

3- Vietnamese is a Latin script, so it is suitable for European languages, so it can reflect all scientific and technical words. Vietnamese is also diversify, reduce words with identical sound and different meanings because the creator of Vietnamese has devised 5 marks and 5 carets for vowels.

4- Vietnamese people learn English, French, German and Portuguese easier than learning Japanese, Korean and Chinese. Due to the Latin script, the keyboard can be used by English speakers (which is an international language).

5- Vietnamese language is unique, not borrowed from other languages and designed specifically for Vietnam and after only a few years has created for Vietnam a new culture, great literature.

6. Thanks to the Vietnamese language, Vietnamese people have a very high literacy rate even though the education budget is not large. Vietnam is one of the countries with highly literate people in the world (about 98%). 2% of illiterate people are the elderly, ethnic minorities. Literacy rates will still increase as the economy improves.

7. Vietnamese helps Vietnamese people in communication and work. An ordinary Vietnamese person can understand the whole meaning of a Vietnamese dictionary except for some specialized terms. Most Vietnamese literate people can read and understand an entire novel with tens of thousands of words without looking up a dictionary.

8. Vietnamese language also helps Vietnamese people improve their learning ability even though Vietnam is still poor and the budget for education is small. In the PISA exams, Vietnam's performance is quite good. Certainly, Vietnamese language plays an important role to upgrade the Vietnamese knowledge.

Conclusion: I only mentioned a few benefits of Vietnamese, it is not possible to list all the benefits of Vietnamese here. President Ho Chi Minh made the right choice in 1945 when choosing Vietnamese as the National Language. Although the people who designed the Vietnamese language used it to serve the interests of France, the Vietnamese people should appreciate and acknowledge their contribution to Vietnam.

Was the reason why Vietnam changed their writing system from Chữ Nôm to the Latin alphabet was to differentiate themselves from the Chinese? Is the Vietnamese alphabet ugly?

Why does every writing system has to become so complicated when used to write the Vietnamese language? The alphabet has a lot of diacritics and Chu Nom has a lot of characters.

Profile photo for Anonymous Answered Mar 17, 2017

No I don't think it's a wise choice

I can't even read what's on my ancestors shrine when we go there to light incense

My family has a family book with all our ancestors details and I can't read it

It's a problem when people walk into a historical site and the only thing they understand is the donation box

It's a problem when tourists from other countries explain and teach Vietnamese about their own culture

All the poetry on the walls become hieroglyphs

All the arts like calligraphy can no longer be fully appreciated

Vietnam becomes a hybrid quái thai civilization and nobody respects us

Latin script is just ugly in my opinion. Yes feel free to hate me but it's my opinion

Yes I think we should have developed another system based on Chinese characters and Chu Nom. That is our real heritage.

In the past public education is not available so of course everyone is illiterated. In the past education is only for nobilitlies. Now it is different, so the difficulty of the script cannot be blamed for low literacy. China never had problem once public education is available

Vietnam’s switch to Latin alphabet is a disconnection between the past and the present. A deliberate destruction of our cultural heritage which is just as rich and beautiful and China Japan or Korea

Even the Koreans realize that and began to teach characters again in schools

And why did Vietnam do this? More than just to spread literacy, it was to make Vietnam more advanced since Asia was poor and undeveloped back then. China, the biggest power in Asia collapsed. Vietnamese were not confident in their Asian heritage anymore and thought Western culture was better. Similar to reasons the Japanese underwent Meiji restoration and got rid of their traditional calendar.

Vietnam would be a more interesting country had it stuck with developing its own cultural heritage

I just don't understand what's so beautiful about this. Not only is it difficult to read , it is so nguệch ngoạc it looks like scribbles

I absolutely hate Quốc ngữ temples. They are so ugly in my opinion. Do you ever see girls trying to take photos with them?

I bet I'm not the only one thinking this way. If Vietnamese are so confident with the Latin alphabet why the need to force it to look like characters?

Dor Kimp , Vietnamese Answered Apr 14, 2016

This question has been asked to death.

The Latin alphabet entered Vietnam at the time European missionaries travelled to Asia to spread the gospel. Portuguese missionaries found that it took too long for a native person to be literate because of the complicated Chinese characters that Vietnam used before which slowed down their evangelisation effort. It has nothing to do with French colonisation as mentioned in the other answers. Many Vietnamese continued a Hanzi education , most notably Ho Chi Minh.

Vietnam adopted the Latin alphabet mainly because the revolutionists advocated for it as they saw it as a quick way to get the masses educated and thus can join in the revolutionary effort. If the revolutionists opted for Chinese characters or Chu Nom then I think today Vietnam will use chinese characters/Chu nom. I don't see it any difference than English or German adopting Latin alphabet when they are Germanic languages. It's quite laughable that people continue to think it was the French effort to destroy Vietnamese culture? To be honest , the French did less to destroy Vietnamese culture than the Americans and also French rule was indirect , they mainly took control via a puppet government and elite class. They did not march in and conquered everyone like people imagine.

Vietnamese did not lose any root or culture by switching to the Latin alphabet, mainly because the alphabet is just a phonetic tool to transcribe the pronunciation. All Chu nom and chinese texts have been transcribed phonetically so now we are able to preserve their rhymes forever. And yes, Vietnamese understand Chu nom literature just fine, hell we can also understand Classical Chinese poems provided they are not too obscure. About homophones Vietnamese has a wide range of sounds so there are way less homophones in Vietnamese comparing to other languages.

Is it a wise move? Depends which side you're on. People who like chinese characters and chinese civilisation see it as a real pity, people who don't like China because of whatever political reason see it as a relief, people who don't care much besides their own life don't think much of it, to them it's just a writing system. As for our cultural struggle against China, yes it exists, mainly because Vietnam as a nation exists on a duality, that is our cultural identity is tied to China but we see China as the enemy at the same time.

Cheong Tee

“Vietnamese did not lose any root or culture by switching to the Latin alphabet” — that’s only if you consider subtle or even profound connection to ancestry is not important. There are fundamental differences in phonetic writing versus ‘pictorial’, it affects deep cultural and language constructs.

Earl Myers · January 31, 2020

I was in Vietnam 18 months and never got a straight answer to this question…..till now…thanks!

Nguyen Vinh Phuc , lived in Vietnam Answered Aug 5

Before being a cultural element, writing is simply a means of recording and transmitting knowledge. Acquiring knowledge is the core problem. Learning chu quoc ngu is very easier than learning chinese scripts or chu han nom. Learning chu quoc ngu helps quick acquisition of knowledge.

Chinese writing (Chinese scripts) is surely not the writing for the Vietnamese although in the past, governing China wanted it; han nom is partially the writing for the Vietnamese because VietNam has not its entirely own wrting, or in the past, VN had its own writing but it has been destroyed by governing China. Chu quoc ngu though meaning national writing, has been understood as the writing of the Vietnamese nation, although using the Latin alphabet instead of the chinese scripts.

I think the choice of chu quoc ngu has helped Viet Nam not only to acquire its independence, but also to quickly become an important nation in the region and in the world. Juste choice, happy choice.

Walter John Burgess Answered Jul 31, 2021

A Portuguese Jesuit priest developed the Romanized Vietnamese script in the 1750’s and the French imposed the Romanized script on their office workers and in newspapers from the 1850’s onwards instead of the Chinese script. By 1954 it was the main script taught throughout Vietnam in schools ijhnstead of the Chinese csriopt. It also increased the literacy rate within Vietnam It was certainly imposed by the Diem regime from 1954 onwards instead of other scdxripts and languagews (Khmer, Chinese etc).

Anh Pham Answered Oct 20

Did you try learning Chinese? It is a very difficult language to learn, especially in writing. It takes years and years of learning and practice.

Chinese was the official language in Vietnam for hundreds of years but it was mostly the elites who could afford to learn how to read and write. In the old days, only a wealthy family could afford to hire a teacher for their children and even for a wealthy family it was a considerable sum. Typically, they must cover his salary, provide him with food, clothing and accommodation and occasional holidays. Most people couldn’t even dream of being able to afford a teacher.

That’s why 99% of the population was illiterate up until quite recently.

The Latin alphabet solved this problem. It was easy to learn and thanks to the education system put in by the French, a significant number of Vietnamese were already familiar with it. It was much much easier to just adopt it compared to the Chinese alphabet, which was also just another foreign language to most people anyway.

Some Chinese on Quora like to say Chinese has been the language of Vietnam for thousands of years. This is only partially true.

Spoken Vietnamese is very old but we never had a written language. For various reasons, the Chinese alphabet filled that void but never replaced our spoken language.

For the vast majority of Vietnamese, Chinese characters may as well be Korean or Japanese. Most can’t tell them apart, except maybe for very basic characters.

Sam Eaton Answered Jan 18, 2018

Yes. In fact I would say that with the addition of tones through the use of the Latin alphabet, and using the diacritical marks available using the Vietnamese modified Latin alphabet, written Vietnamese has become much more precise and understandable.

Jeff

, Once I too aspired to learn these languages. I still do.

Answered Apr 14, 2016

Vietnam was colonized by the French for roughly a century. Japan was never colonized, Korea was only colonized by the Japanese, and while parts of China were occupied by Europeans and Americans, control over most of the country was never accomplished by people using said alphabet.

As to the wisdom, it reinforces the cultural struggle against China which goes back two thousand years and gives them a leg up on learning European languages. There is a certain advantage to that, but I suspect Mandarin will become steadily more common in Vietnamese higher education as a foreign language, just as it is in many other parts of the world, including the USA.

Jack Noone

· April 14, 2016

I doubt the fact Vietnam has a Latin alphabet means that they have an advantage in learning European languages, Chinese students would have some grounding in Latin characters through pinyin, and in any case, it doesn't take that much time to learn the alphabet if you take it seriously enough.

Jeff · April 14, 2016

Yeah the older generation with French experience would have certainly had an advantage, but for younger non-French speakers you are probably correct. My main point was colonial influence was probably the deciding factor in the choice of an European alphabet.

Joseph Boyle , lives in California (1988-present) Answered Apr 14, 2016

Compatibility is an actual benefit.

Bragging you invented something incompatible is not.

Jack Noone , studied at University of Leeds (2017) Answered Apr 14, 2016

As has been mentioned, the French colonised Vietnam for over a century. It has been argued that changing the writing system was an attmpt to cut off the Vietnamese from their roots, as they would be unable to read Vietnamese literature in Chu Nom. As for would a Latin alphabet work for other East Asian languages, no, it wouldn't, East Asian languages have a high number of homophones, without characters, sometimes it is difficult to distinguish between homophonic words. Mao found this out when he started his attempt at abolishing Chinese characters, in the end he settled on the current set of simplified characters. Korean has a fully alphabetic system, albeit there are occasional difficulties due to homophones. In any case, it doesn't help literacy rates all that much, even China's literacy rates are higher than Vietnam's.

Personally, I think aside from China's fully logographic script, written Japanese works well too, as it has its own 'native' (perhaps influenced by Chinese) systems for grammar and non-Sinitic vocabulary, while it incorporates Kanji to help reduce homophonic confusions too.

Francisco Rivas · November 14, 2016

The “evil French forcing Quốc ngữ on Vietnamese people’s throats to divorce them from their past” rhetoric is as much of a myth as “the evil CCP forcing simplified characters on Chinese people’s throats to divorce them from their past” one, as some other answers have stated.

More importantly, Mao didn’t abandon the idea of latinizing Chinese due to homophones, he did it because it would pose logistic problems with speakers of other Chinese languages (and because abolishing one of the pillars of Chinese unity might have made southern Chinese people rebel).

Lea Lea · March 17, 2017

The simplified Chinese has been used for handreds to thousands years old. It is a natural development of Chinese characters. It is not CCP to force to use simplified Chinese. Simplified Chinese is started and advocated before CCP appears. Nowdasys the traditional Chinese is forced used by dictator Jiang Jieshi in Taiwan. Even Chinese character in Japan is simplified by Japanese.

Francisco Rivas · March 19, 2017

You clearly didn't understand my comment, you're misrepresenting the existence of simplified Chinese characters in Chinese history (as well as in Japan), and you're outright lying about the situation in Taiwan. Very nice comment.

Hải Phong Nguyễn · December 5

What France colonists want is VN learn France , not latin Vietnamese script.

The reason latin Vietnamese script became more and more popular is because some Vietnamese found the uselful and suitable Latin-Vietnamese script to Vietnamese compare with Chinese script or borrowed Chinese script (Nôm script)

Richard qq Chen , I just visited Saigon, where I visited in 2005.

Updated Dec 17, 2016

Latinization is a bad idea for Japan and China, because both countries will lose an important part of their culture. I guess it also apples to Korea and Vietnam.

Lucky for the Chinese, China made a try in the 1950s and failed.

I didn't find any record about Japan wanted latinization.

I recognize Chinese characters were not easy to learn, but I don't think Korea and Vietnamese totally gave up Chinese characters was a good choice. Chinese and Japanese educated their children very well without giving up Chinese characters.

I think the real reason is Vietnam and Korea lacked of confidence, they wanted to get rid of the influences of Chinese culture. But I guess they will embrace Chinese characters again in the future, some South Korean are requesting using Chinese characters again.

Matthew Nghiem · April 15, 2016

Personally, as Chinese-Vietnamese, I think that although Latinisation is practical, getting rid of Characters was a disappointing part of our history indeed.

Dor Kimp · April 14, 2016

You made a good point about lack of confidence. This is definitely true for Vietnam. We often run into identity crisis where we are unsure of whether to embrace things that originated from China or not. A few weeks ago was the cold food festival and many people posted photos of their special food on facebook . Some people commented asking why we are still celebrating a Chinese festival and that it should be abolished. Sigh.

Theclowcard .

· November 7, 2017

Not in the slightest. Ask the majority of Vietnamese peopel and they will absolutely reject introducing Chinese back into the writing system. Many efforts have been made for the aforementioned purpose but they all failed in the end. The people want less Sinicization and they achieve it with the Latin alphabet. That’s all

San Do , Master dishwasher (2012-present)

It is the Latin alphabet that chose Vietnam and because of that, Vietnam writing system has developed the modern alphabet.

Sài Gòn có bến Chương Dương,

Có dinh Độc Lập, có đường Tự Do.