Trồng Lúa - Rice Cultivation

Các loại xôi

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

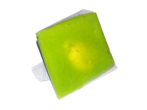

11 Xôi gấc

12 Xôi gấc

Thần Nông - Thủy tổ của người Việt và Bách Việt

| Phả hệ Đế Viêm Thần Nông thị | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Glutinous rice

• Gạo nếp

1

Glutinous rice (Oryza sativa var. glutinosa; also called sticky rice, sweet rice or waxy rice) is a type of rice grown mainly in Southeast Asia and East Asia, and the northeastern regions of South Asia, which has opaque grains, very low amylose content, and is especially sticky when cooked. It is widely consumed across Asia.

It is called glutinous (Latin: glūtinōsus)[1] in the sense of being glue-like or sticky, and not in the sense of containing gluten (which it does not). While often called sticky rice, it differs from non-glutinous strains of japonica rice, which also become sticky to some degree when cooked. There are numerous cultivars of glutinous rice, which include japonica, indica and tropical japonica strains.

History[edit]

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (May 2013) |

Glutinous rice has been grown for at least 2,000 years.[2]Researchers believe that glutinous rice distribution appears to have been culturally influenced and closely associated with the early southward migration and distribution of the Tai ethnic groups, particularly the Lao people along the Mekong River basin originating from Southern China. Along the Greater Mekong Sub-region, the Lao have been cultivating glutinous rice for approximately 4000 - 6000 years.[3]

The history of rice cultivation in Thailand dates back over 5,000 years. Different types of rice have been cultivated in various regions during different historical periods, including glutinous rice, large-grain rice, and slender grain rice. Through archaeological research, Japanese scholars found that fortified grain was likely the glutinous-lowland variety of glutinous rice, and large-grain rice was likely glutinous rice that thrives at high altitudes. Meanwhile, slender grain rice is non-glutinous. Sticky rice has been a staple food in all regions from north to south since about 3,000 years ago, and it has played an essential role in the country's food culture[4][5]

Cultivation

Glutinous rice is grown in Laos, Thailand, Cambodia, Vietnam, Malaysia, Indonesia, Myanmar, Nepal, Bangladesh, Bhutan, Northeast India, China, Japan, Korea, Taiwan, and the Philippines. An estimated 85% of Lao rice production is of this type.[6] The rice has been recorded in the region for at least 1,100 years.[7]

As of 2013, approximately 6,530 glutinous rice varieties were collected from five continents (Asia, South America, North America, Europe, and Africa) where glutinous rice is grown for preservation at the International Rice Genebank (IRGC).[3] The International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) has described Laos as a "collector's paradise".[8] Laos has the largest biodiversity of sticky rice in the world. IRRI-trained collectors gathered more than 13,500 samples and 3,200 varieties from Laos alone.[8]

Compositionedit

Glutinous rice is distinguished from other types of rice by having no (or negligible amounts of) amylose and high amounts of amylopectin (the two components of starch). Amylopectin is responsible for the sticky quality of glutinous rice. The difference has been traced to a single mutation that farmers selected.[2][9]

Like all types of rice, glutinous rice does not contain dietary gluten (i.e. does not contain glutenin and gliadin) and should be safe for gluten-free diets.[10]

Glutinous rice can be used either milled or unmilled (that is, with the bran removed or not removed). Milled glutinous rice is white and fully opaque (unlike non-glutinous rice varieties, which are somewhat translucent when raw), whereas the bran can give unmilled glutinous rice a purple or black colour.[11] Black and purple glutinous rice are distinct strains from white glutinous rice. In developing Asia, there is little regulation, and some governments have issued advisories about toxic dyes being added to colour adulterated rice. Both black and white glutinous rice can be cooked as discrete grains or ground into flour and cooked as a paste or gel.[12]

Use in foods[edit]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (

July 2021) |

Sticky rice is used in many recipes throughout Southeast and East Asia, such as in dumplings, as a filling or side in spicy dishes, with beans and fried by itself. (Rice cakes.)

Bangladesh[edit]

In Bangladesh and especially in the Chittagong (Cox's Bazar and Sylhet areas), sticky rice called bini dhan (unhusked sticky rice) is prevalent. Both white and pink varieties are cultivated at many homestead farms. Husked sticky rice is called bini choil (chal) in some dialects. Boiled or steamed bini choil is called Bini Bhat. Served with a curry of fish or meat and grated coconut, Bini Bhat is a popular breakfast. Sometimes it is eaten with a splash of sugar, salt, and coconut alone. Bin dhan is also used to make khoi (popcorn-like puffed rice) and chida (bitten husked rice).

Many other sweet items made of bini choil are also popular:

One of the favourite pitas made of bini choil is atikka pita (pitha). It is made with a mixture of cubed or small sliced coconut, white or brown sugar, ripe bananas and bini choil wrapped with banana leaf and steamed.

Another delicacy is Patishapta pita made of ground bini choil. Ground bini choil is sprayed over a hot pan and a mixture of grated coconut, sugar, and milk powder; then, ghee is sprayed over that and rolled out. Dumplings made of powdered fried bini choil called laru. First, bini choil is fried and ground into flour. This flour is mixed with sugar or brown sugar, and ghee or butter and is made into small balls or dumplings.

One kind of porridge or khir made of bini choil is called modhu (honey) bhat. This modhu bhat becomes naturally sweet without mixing any sugar. It is one of the delicacies of local people. To make modhu bhat first, prepare some normal paddy or rice (dhan) for germination by soaking it in the water for a few days. After coming out of the little sprout dry the paddy and husk and grind the husked rice called jala choil into flour. It tastes sweet. Mixing this sweet flour with freshly boiled or steamed warm bini bhat and then fermenting the mixture overnight yields modhu bhat. It is eaten either on its own or with milk, jaggery or grated coconut.

Cambodia

Glutinous rice is known as bay damnaeb (Khmer: បាយដំណើប) in Khmer.

In Cambodian cuisine, glutinous rice is used exclusively for desserts[13] and is an essential ingredient for most sweet dishes, such as ansom chek, kralan, and num ple aiy.[14]

China

In the Chinese language, glutinous rice is known as nuòmǐ (糯米) or chu̍t-bí (秫米) in Hokkien.

Glutinous rice is also often ground to make glutinous rice flour. This flour is made into niangao and sweet-filled dumplings tangyuan, both of which are commonly eaten at Luna New Year. It is also used as a thickener and for baking.

Glutinous rice or glutinous rice flour are both used in many Căntonese bakery products and in many varieties of dim sum. They produce a flexible, resilient dough, which can take on the flavours of whatever other ingredients are added to it. Cooking usually consists of steaming or boiling, sometimes followed by pan-frying or deep-frying.

Sweet glutinous rice is eaten with red bean paste.

Nuòmǐ fàn (糯米飯), is steamed glutinous rice usually cooked with sausage, chopped mushrooms, chopped barbecued pork, and optionally dried shrimp or scallop (the recipe varies depending on the cook's preference).

Zongzi 糭子 is a dumpling consisting of glutinous rice and sweet or savoury fillings wrapped in large flat leaves (usually bamboo), which is then boiled or steamed. It is especially eaten during the Dragon Boat Festival but may be eaten at any time of the year. It is popular as an easily transported snack, or a meal to consume while travelling. It is a common food among Southern Chinese in Hong Kong, Singapore and Malaysia.

Cifangao 糍飯糕 is a popular breakfast food originating in Eastern China consisting of cooked glutinous rice compressed into squares or rectangles, and then deep-fried.[15] Additional seasoning and ingredients such as beans, zha cai, and sesame seeds may be added to the rice for added flavour. It has a similar appearance and external texture to hash browns.

Cifantuan 糍飯糰 is another breakfast food consisting of a piece of youtiao tightly wrapped in cooked glutinous rice, with or without additional seasoning ingredients. Japanese onigiri resembles this Chinese food.

Lo mai gai (糯米雞) is a dim sum dish consisting of glutinous rice with chicken in a lotus-leaf wrap, which is then steamed. It is served as a dim sum dish in Hong Kong, Singapore, and Malaysia.

Ba bao fan (八寶飯), or "eight treasure rice", is a dessert made from glutinous rice, steamed and mixed with lard, sugar, and eight kinds of fruits or nuts. It can also be eaten as the main course.

A distinctive feature of the Cuisine of the people of Southern China is its variety of steamed snack-type buns, dumplings, and patties made with a dough of coarsely ground rice, or ban. Collectively known as "rice snacks", some kinds are filled with various salty or sweet ingredients.

Common examples of rice snacks made with ban from glutinous or sticky rice and non-glutinous rice[further explanation needed] include Aiban (mugwort patty), Caibao (yam bean bun), Ziba (sticky rice balls) and Bantiao (Mianpaban or flat rice noodles).

Aiban encompasses several varieties of steamed patties and dumplings of various shapes and sizes, consisting of an outer layer made of glutinous ban dough filled with salty or sweet ingredients. It gets its name from the aromatic ai grass (mugwort), which after being dried, powdered, and mixed with the ban, gives the dough a green colour and an intriguing tea-like taste. Typical salty fillings include ground pork, mushrooms, and shredded white turnips. The most common sweet filling is made with red beans.

Caibao is a generic term for all types of steamed buns with various sorts of filling. Hakka-style caibao are distinctive in that the enclosing skin is made with glutinous rice dough in place of wheat flour dough. Besides ground pork, mushrooms, and shredded turnips, fillings may include ingredients such as dried shrimp and dry fried-shallot flakes.

Ziba is glutinous rice dough that, after steaming in a big container, is mashed into a sticky, putty-like mass from which small patties are formed and coated with a layer of sugary peanut powder. It has no filling.

Glutinous zongzi rice dumplings, without and with bamboo leaf wrapping

Philippines

In the Philippines, glutinous rice is known as malagkit in Tagalog or pilit in Visayan, among other names. Both mean "sticky". The most common way glutinous rice is prepared in the Philippines is by soaking uncooked glutinous rice in water or coconut milk (usually overnight) and then grinding it into a thick paste (traditionally with stone mills). This produces a rich and smooth viscous rice dough known as galapóng, which is the basis for numerous rice cakes in the Philippines. However, in modern preparation methods, galapong is sometimes made directly from dry glutinous rice flour (or from commercial Japanese mochiko), with poorer-quality results.[16]

Galapong was traditionally allowed to ferment, which is still required for certain dishes. A small amount of starter culture of microorganisms (tapay or bubod) or palm wine (tubâ) may be traditionally added to rice being soaked to hasten the fermentation. These can be substituted with yeast or baking soda in modern versions.[17][16] Other versions of galapong may also be treated with wood ash lye.

Aside from the numerous white and red glutinous rice cultivars, the most widely used glutinous rice heirloom cultivars in the Philippines are tapol rice, which is milky white in colour, and pirurutong rice, which ranges in colour from black to purple to reddish brown.[18] However both varieties are expensive and becoming increasingly rare, thus some Filipino recipes nowadays substitute it with dyed regular glutinous rice or infuse purple yam (ube) to achieve the same colouration.[19][20][21]

Dessert delicacies in the Philippines are known as kakanin (from kanin, "prepared rice"). These were originally made primarily from rice, but in recent centuries, the term has come to encompass dishes made from other types of flour, including corn flour (masa), cassava, wheat, and so on. Glutinous rice figures prominently in two main subtypes of kakanin: the puto (steamed rice cakes), and the bibingka (baked rice cakes). Both largely utilize glutinous rice galapong. A notable variant of puto is puto bumbong, which is made with pirurutong.

Other kakanin that use glutinous rice include suman, biko, and sapin-sapin among others. There is also a special class of boiled galapong dishes like palitaw, moche, mache, and masi. Fried galapong is also used to make various types of buchi, which are the local Chinese-Filipino versions of jian dui. They are also used to make puso, which are boiled rice cakes in woven leaf pouches.

Aside from kakanin, glutinous rice is also used in traditional Filipino rice gruels or porridges known as lugaw. They include both savory versions like arroz caldo or goto which are similar to Chinese-style congee; and dessert versions like champorado, binignit, and ginataang mais.

Puto, steamed rice cakes made with fermented galapong

Bibingka, made from baked galapong with coconut milk

Puto bumbong, steamed rice cakes made with purple glutinous rice, steamed in bamboo tubes

Ginataang mais, a dessert lugaw (rice gruel) with coconut milk and sweet corn

Arroz caldo, savoury lugaw with chicken, ginger, toasted garlic, scallions, and safflower

Champorado, dessert lugaw made from glutinous rice and chocolate

Puto pandan, a type of puto infused with pandan leaves, turning it light green

Suman sa ibus, a type of suman, steamed glutinous rice packaged in tagbak leaves

Moche, boiled glutinous rice filled with bean paste

Sapin-sapin, a colourful dessert made with multiple layers of glutinous rice, each with a different flavour and texture

Pusô, made from glutinous rice cooked in pouches of woven coconut leaves

Puto maya made with pirurutong rice

Indonesia[edit]

Glutinous rice is known as beras ketan or simply ketan in Java and most of Indonesia, and pulut in Sumatra. It is widely used as an ingredient for a wide variety of sweet, savoury, or fermented snacks. Glutinous rice is used as either hulled grains or milled into flour. It is usually mixed with santan, meaning coconut milk in Indonesian, along with a bit of salt to add some taste. Glutinous rice is rarely eaten as a staple. One example is lemang, which is glutinous rice and coconut milk cooked in bamboo stems lined by banana leaves. Glutinous rice is also sometimes used in a mix with normal rice in rice dishes such as nasi tumpeng or nasi tim. It is widely used during the Lebaran seasons as traditional food. It is also used in the production of alcoholic beverages such as tuak and brem bali.

Savoury snacks[edit]

- Ketan - traditionally refers to the glutinous rice itself as well as sticky rice delicacy in its simplest form. The handful mounds of glutinous rice are rounded and sprinkled with grated coconut, either fresh or sauteed as serundeng.

- Ketupat - square-shaped crafts made from the same local leaves as palas, but it is usually filled with regular rice grains instead of pulut, though it depends on the maker.

- Gandos - a snack made from ground glutinous rice mixed with grated coconut, and fried.

- Lemang - wrapped in banana leaves and inside a bamboo, and left to be barbecued/grilled on an open fire, to make the taste and texture tender and unique

- Lemper - cooked glutinous rice with shredded meat inside and wrapped in banana leaves, popular in Java

- Nasi kuning - either common rice or glutinous rice can be made into ketan kuning, yellow rice coloured with turmeric

- Songkolo or Sokko - steamed black glutinous rice serves with serundeng, anchovies, and sambal. It was very popular in Makassar

- Tumpeng - glutinous rice can be made into tumpeng nasi kuning, yellow rice coloured by turmeric, and shaped into a cone.

Sweet snacks[edit]

- Variety of kue - glutinous rice flour is also used in certain traditional local desserts, known as kue, such as kue lapis.

- Bubur ketan hitam - black glutinous rice porridge with coconut milk and palm sugar syrup

- Candil - glutinous rice flour cake with sugar and grated coconut

- Dodol - traditional sweets made of glutinous rice flour and coconut sugar. Similar variants include wajik (or wajit).

- Gemblong - white glutinous rice flour balls smeared with palm sugar caramel. In East Java, it was known as getas, except it uses black glutinous rice flour as the main ingredient.

- Jipang (food) - popped glutinous rice held together by caramelized sugar

- Klepon - glutinous rice flour balls filled with palm sugar and coated with grated coconut

- Lupis - glutinous rice wrapped in individual triangles using banana leaves and left to boil for a few hours. The rice pieces are then tossed with grated coconut all over and served with palm sugar syrup.

- Onde-onde - glutinous rice flour balls filled with sweetened mung bean paste and coated with sesame similar to Jin deui

- Wingko babat - baked glutinous rice flour with coconut

Fermented snacks[edit]

- Brem - solid cake from the dehydrated juice of pressed fermented glutinous rice

- Tapai ketan - cooked glutinous rice fermented with yeast, wrapped in banana or roseapple leaves. Usually eaten as it is or in a mixed cold dessert

Crackers[edit]

- Rengginang - traditional rice crackers related to kerupuk

In addition, glutinous rice dishes adapted from other cultures are just as easily available. Examples include kue moci (mochi, Japanese) and bacang (zongzi, Chinese).

Lemper, glutinous rice filled with chicken wrapped in banana leaves

Dodol made from coconut sugar and ground glutinous rice

Bubur ketan hitam, black glutinous rice porridge with coconut milk and palm sugar

Ketan served with durian sauce

Kue lupis - Glutinous rice cake with grated coconut and liquid palm sugar

Tapai ketan (right) served with uli (glutinous rice cooked with grated coconut, and mashed; left)

Japan[edit]

In Japan, glutinous rice is known as mochigome (Japanese: もち米). It is used in traditional dishes such as sekihan also known as Red bean rice, okowa, and ohagi. It may also be ground into mochiko (もち粉) a rice flour, used to make mochi (もち) which are known as sweet rice cakes. Mochi a traditional rice cake prepared for the Japanese New Year but also eaten year-round. Many different types of mochi exist from different regions, and they are normally flavoured with traditional ingredients red beans, water chestnuts, green tea and pickled cherry flowers. See also Japanese rice.

Korea[edit]

In Korea, glutinous rice is called chapssal (Hangul: 찹쌀), and its characteristic stickiness is called chalgi (Hangul: 찰기). Cooked rice made of glutinous rice is called chalbap (Hangul: 찰밥) and rice cakes (Hangul: 떡, ddeok) are called chalddeok or chapssalddeok (Hangul: 찰떡, 찹쌀떡). Chalbap is used as stuffing in samgyetang (Hangul: 삼계탕).

Laos[edit]

Along the Greater Mekong Sub-region, the Lao have been cultivating glutinous rice for approximately 4000 - 6000 years.[3] Glutinous rice is the national dish of Laos.[22] In Laos, a tiny landlocked nation with a population of approximately 6 million, per-capita sticky rice consumption is the highest on earth at 171 kg or 377 pounds per year.[23][24] Sticky rice is deeply ingrained in the culture, religious tradition, and national identity of Laos (see Lao cuisine). Sticky rice is considered the essence of what it means to be Lao. It has been said that no matter where they are in the world, sticky rice will always be the glue that holds the Lao communities together, connecting them to their culture and to Laos.[8] Lao people often identify themselves as the "children of sticky rice"[25] and if they did not eat sticky rice, they would not be Lao.[26][27]

Sticky rice is known as khao niao (Lao:ເຂົ້າໜຽວ): khao means rice, and niao means sticky. It is cooked by soaking for several hours and then steaming in a bamboo basket or houat (Lao: ຫວດ). After that, it should be turned out on a clean surface and kneaded with a wooden paddle to release the steam; this results in rice balls that will stick to themselves but not to fingers. The large rice ball is kept in a small basket made of bamboo or thip khao (Lao:ຕິບເຂົ້າ). The rice is sticky but dry, rather than wet and gummy-like non-glutinous varieties. Laotians consume glutinous rice as part of their main diet; they also use toasted glutinous rice khao khoua (Lao:ເຂົ້າຄົ່ວ) to add a nut-like flavour to many dishes. A popular Lao meal is a combination of larb (Lao:ລາບ), Lao grilled chicken ping gai (Lao:ປີ້ງໄກ່), spicy green papaya salad dish known as tam mak hoong (Lao:ຕຳໝາກຫູ່ງ), and sticky rice (khao niao).

- Khao lam (Lao:ເຂົ້າຫລາມ): sticky rice is mixed with coconut milk, red or black bean, or taro, and is filled in a bamboo tube. The tube is roasted until all the ingredients are cooked and blended together to give a sweet aromatic treat. Khao Lam is such a popular food for Laotians and is sold on the streets.

- Nam Khao (Lao:ແໝມເຂົ້າ): sticky rice has also been used for preparing a popular dish from Laos called Nam Khao (or Laotian crispy rice salad). It is made with a deep-fried mixture of sticky rice and jasmine rice balls, chunks of Lao-style fermented pork sausage called som moo, chopped peanuts, grated coconut, sliced scallions or shallots, mint, cilantro, lime juice, fish sauce, and other ingredients.

- Khao Khua (Lao:ເຂົ້າຂົ້ວ): sticky rice are toasted and crushed. Khao Khua is a necessary ingredient for preparing a national Laotian dish called Larb (Lao:ລາບ) and Nam Tok (Lao:ນ້ຳຕົກ) that are popular for ethnic Lao people living in both Laos and in the Northeastern region of Thailand called Isan.

- Khao tom (Lao:ເຂົ້າຕົ້ມ): a steamed mixture of khao niao with sliced fruits and coconut milk wrapped in banana leaf.

- Khao jee: Lao sticky rice pancakes with egg coating, an ancient Laotian cooking method of grilling glutinous rice or sticky rice over an open fire.

- Sai Krok (Lao:ໄສ້ກອກ): Lao sausage made from coarsely chopped fatty pork seasoned with lemongrass, galangal, kaffir lime leaves, shallots, cilantro, chillies, garlic, salt, and sticky rice.

- Or lam (Lao:ເອາະຫຼາມ): a mildly spicy and tongue-numbing stew originating from Luang Prabang, Laos.

- Lao-Lao (Lao:ເຫລົ້າລາວ): Laotian rice whisky produced in Laos.

Khao niao is also used as an ingredient in desserts. Khao niao mixed with coconut milk can be served with ripened mango or durian.

Malaysia[edit]

In Malaysia, glutinous rice is known as pulut. It is usually mixed with santan (coconut milk) along with a bit of salt to add some taste. It is widely used during the Raya festive seasons as traditional food which is shared with certain parts of Indonesia, such as:

- Dodol - traditional sweets made of glutinous rice flour and coconut sugar. Similar variants are wajik (or wajit).

- Inang-inang - glutinous rice cracker. Popular in Melaka.

- Kelupis - a type of glutinous rice kuih in East Malaysia.

- Ketupat - square-shaped crafts made from the same local leaves as palas, but it is usually filled with regular rice grains instead of pulut, though it depends on the maker.

- Kochi - Malay-Peranakan sweet and sticky kuih.

- Lamban - another type of glutinous rice dessert in East Malaysia.

- Lemang - wrapped in banana leaves and inside a bamboo, and left to be barbecued/grilled on an open fire, to make the taste and texture tender and unique.

- Pulut inti – wrapped in banana leaf in the shape of a pyramid, this kuih consists of glutinous rice with a covering of grated coconut candied with palm sugar.

- Pulut panggang – glutinous rice parcels stuffed with a spiced filling, then wrapped in banana leaves and char-grilled. Depending on the regional tradition, the spiced filling may include pulverised dried prawns, caramelised coconut paste or beef floss. In the state of Sarawak, the local pulut panggang contains no fillings and is wrapped in pandan leaves instead.

- Tapai - cooked glutinous rice fermented with yeast, wrapped in banana, rubber tree or roseapple leaves.

Myanmar[edit]

Glutinous rice, called kao hnyin (ကောက်ညှင်း), is very popular in Myanmar (also known as Burma).

- Kao hnyin baung (ကောက်ညှင်းပေါင်း) is a breakfast dish with boiled peas (pèbyouk) or with a variety of fritters, such as urad dal (baya gyaw), served on a banana leaf. It may be cooked wrapped in a banana leaf, often with peas, and served with a sprinkle of salted toasted sesame seeds and often grated coconut.

- The purple variety, known as kao hynin ngacheik (ကောင်းညှင်းငချိမ့်), is equally popular cooked as ngacheik paung.

- They may both be cooked and pounded into cakes with sesame called hkaw bouk, another favourite version in the north among the Shan and the Kachin, and served grilled or fried.

- The Htamanè pwè festival (ထမနဲပွဲ) takes place on the full moon of Dabodwè(တပို့တွဲ) (February), when htamanè (ထမနဲ) is cooked in a huge wok. Two men, each with a wooden spoon the size of an oar, and a third man coordinate the action of folding and stirring the contents, which include kao hnyin, ngacheik, coconut shavings, peanuts, sesame and ginger in peanut oil.

- Si htamin (ဆီထမင်း) is glutinous rice cooked with turmeric and onions in peanut oil, and served with toasted sesame and crisp-fried onions; it is a popular breakfast like kao hnyin baung and ngacheik paung.

- Paung din (ပေါင်းတင်) or "Kao hyin kyi tauk" (ကောင်းညှင်းကျည်တောက်) is another ready-to-eat portable form cooked in a segment of bamboo. When the bamboo is peeled off, a thin skin remains around the rice and also gives off a distinctive aroma.

- Mont let kauk (မုန့်လက်ကောက်) is made from glutinous rice flour; it is donut-shaped and fried like baya gyaw, but eaten with a dip of jaggery or palm sugar syrup.

- Nga pyaw douk (ငပျောထုပ်) or "Kao hynin htope" (ကောင်းညှင်းထုပ်), banana in glutinous rice, wrapped in banana leaf and steamed and served with grated coconut - another favourite snack, like kao hnyin baung and mont let kauk, sold by street hawkers.

- Mont lone yay baw (မုန့်လုံးရေပေါ်) are glutinous rice balls with jaggery inside, thrown into boiling water in a huge wok, and ready to serve as soon as they resurface. Their preparation is a tradition during Thingyan, the Burmese New Year festival.

- Htoe mont (ထိုးမုန့်), glutinous rice cake with raisins, cashews and coconut shavings, is a traditional dessert for special occasions. It is appreciated as a gift item from Mandalay.

Ngacheik paung with pèbyouk (boiled peas) and salted toasted sesame

Hkaw bouk - dried cakes of ngacheik glutinous rice with Bombay duck, both fried

Htamanè - glutinous rice with fried coconut, roasted peanuts, sesame and ginger

Si htamin - glutinous rice cooked in oil with turmeric and served with boiled peas and crushed salted sesame

Mont lone yei baw - glutinous rice balls filled with jaggery, covered with shredded coconut - a New Year treat

Paung din (ngacheik) with to hpu (Burmese tofu), mashed potato and black gram fritters

Nepal[edit]

In Nepal, Latte/Chamre is a popular dish made from glutinous rice during Teej festival, the greatest festival of Nepalese women.

Northeastern India[edit]

Sticky rice called bora saul is the core component of indigenous Assamese sweets, snacks, and breakfast. This rice is widely used in the traditional sweets of Assam, which are very different from the traditional sweets of India whose basic component is milk.

Such traditional sweets in Assam are Pitha (Narikolor pitha, Til pitha, Ghila pitha, Tel pitha, Keteli pitha, Sunga pitha, Sunga saul etc.). Also, its powder form is used as breakfast or other light meals directly with milk. They are called Pitha guri (if the powder was done without frying the rice, by just crushing it after soaking) or Handoh guri (if rice is dry fried first, and then crushed).

The soaked rice is also cooked with no added water inside a special kind of bamboo (called sunga saul bnaah). This meal is called sunga saul.

During religious ceremonies, indigenous Assamese communities make Mithoi (Kesa mithoi and Poka mithoi) using Gnud with it. Sometimes Bhog, Payokh are also made from it using milk and sugar with it.

Different indigenous Assamese communities make rice beer from sticky rice, preferring it over other varieties of rice for the sweeter and more alcoholic result. This rice beer is also offered to their gods and ancestors (demi-gods). Rice cooked with it is also taken directly as lunch or dinner on rare occasions. Similarly, other indigenous communities from NE India use sticky rice in various forms similar to the native Assamese style in their cuisine.[further explanation needed]

Thailand[edit]

In Thailand, glutinous rice is known as khao niao (Thai: ข้าวเหนียว; lit. 'sticky rice') in central Thailand and Isan, and as khao nueng (Thai: ข้าวนึ่ง; lit. 'steamed rice') in northern Thailand.[28] Sticky rice at the table is typically served individually in a small woven basket (Thai: กระติบข้าว, RTGS: kratip khao).

- Steamed glutinous rice is one of the main ingredients in making the sour-fermented pork skinless sausage called naem, or its northern Thai equivalent chin som, which can be made from pork, beef, or water buffalo meat. It is also essential for the fermentation process in the northeastern Thai sausage called sai krok Isan. This latter sausage is made, in contrast to the first two, with a sausage casing.[29][30][31]

- Sweets and desserts: Famous among tourists in Thailand is khao niao mamuang (Thai: ข้าวเหนียวมะม่วง): sweet coconut sticky rice with mango, while khao niao tat, sweet sticky rice with coconut cream and black beans,[32] Khao niao na krachik (Thai: ข้าวเหนียวหน้ากระฉีก), sweet sticky rice topped with caramelized roasted grated coconut,[33] khao niao kaeo, sticky rice cooked in coconut milk and sugar and khao tom hua ngok, sticky rice steamed with banana with grated coconut and sugar, are traditional popular desserts.[34]

- Khao lam (Thai: ข้าวหลาม) is sticky rice with sugar and coconut cream cooked in specially prepared bamboo sections of different diameters and lengths. It can be prepared with white or dark purple (khao niao dam) varieties of glutinous rice. Sometimes a few beans or nuts are added and mixed in. Thick khao lam containers may have a custard-like filling in the centre made with coconut cream, egg and sugar.

- Khao chi (Thai: ข้าวจี่) are cakes of sticky rice having the size and shape of a patty and a crunchy crust. In order to prepare them, the glutinous rice is laced with salt, often also lightly coated with beaten egg, and grilled over a charcoal fire. They were traditionally made with leftover rice and given in the early morning to the children, or to passing monks as an offering.[35]

- Khao niew tua dum is a sticky with sugar, thickened coconut milk and black beans.

- Khao pong (Thai: ข้าวโป่ง) is a crunchy preparation made of leftover steamed glutinous rice that is pounded and pressed into thin sheets before being grilled.

- Khao tom mat (Thai: ข้าวต้มมัด), cooked sticky rice mixed with banana and wrapped in banana leaf,[36] khao ho, sticky rice moulded and wrapped in a conical shape, khao pradap din, kraya sat and khao thip are preparations based on glutinous rice used as offerings in religious festivals and ceremonies for merit-making or warding off evil spirits.

- Khao niao ping (Thai: ข้าวเหนียวปิ้ง), sticky rice mixed with coconut milk and taro (khao niao ping pheuak), banana (khao niao ping kluai) or black beans (khao niao ping tua), wrapped in banana leaf and grilled slowly over a charcoal fire.[37] Glutinous rice is traditionally eaten using the right hand[38][39]

- Khao khua (Thai: ข้าวคั่ว), roasted ground glutinous rice, is indispensable for making the northeastern Thai dishes larb, nam tok, and nam chim chaeo. Some recipes also ask for khao khua in certain northern Thai curries.[40] It imparts a nutty flavour to the dishes in which it is used.[41]

- Naem khluk (Thai: ยำแหนม) or yam naem khao thot is a salad made from crumbled deep-fried, curried-rice croquettes, and naem sausage[42]

- Chin som mok is a northern Thai speciality made with grilled, banana leaf-wrapped pork skin that has been fermented with glutinous rice

- Sai krok Isan: grilled, fermented pork sausages, a speciality of northeastern Thailand

- Glutinous rice is also used as the basis for the brewing of sato (Thai: สาโท), an alcoholic beverage also known as "Thai rice wine".

Kratip (Thai: กระติบ) are used by northern and northeastern Thais as containers for sticky rice

Vietnam

Glutinous rice is called gạo nếp in Vietnamese. Dishes made from glutinous rice in Vietnam are typically served as desserts or side dishes, but some can be served as main dishes. There is a wide array of glutinous rice dishes in Vietnamese cuisine, the majority of them can be categorized as follows:

- Bánh, the most diverse category, refers to a wide variety of sweet or savoury, distinct cakes, buns, pastries, sandwiches, and food items from Vietnamese cuisine, which may be cooked by steaming, baking, frying, deep-frying, or boiling. It is important to note that not all bánh are made from glutinous rice; they can also be made from ordinary rice flour, cassava flour, taro flour, or tapioca starch. The word "bánh" is also used to refer to certain varieties of noodles in Vietnam, and absolutely not to be confused with glutinous rice dishes. Some bánh dishes that are made from glutinous rice include:

- Bánh chưng: a square-shaped, boiled glutinous rice dumpling filled with pork and mung bean paste, wrapped in a dong leaf, usually eaten in Vietnamese New Year.

- Bánh giầy: white, flat, round glutinous rice cake with a tough, chewy texture filled with mung bean or served with Vietnamese sausage (chả), usually eaten in Vietnamese New Year with bánh chưng.

- Bánh dừa: glutinous rice mixed with black bean paste cooked in coconut juice, wrapped in coconut leaf. The filling can be mung bean stir-fried in coconut juice or banana.

- Bánh rán: a northern Vietnamese dish of deep-fried glutinous rice balls covered with sesame, scented with a jasmine flower essence, filled with either sweetened mung bean paste (the sweet version) or chopped meat and mushrooms (the savoury version).

- Bánh cam: a southern Vietnamese version of bánh rán. Unlike bánh rán, bánh cam is coated with a layer of sugary liquid and has no jasmine essence.

- Bánh trôi: made from glutinous rice mixed with a small portion of ordinary rice flour (the ratio of glutinous rice flour to ordinary rice flour is typically 9:1 or 8:2) filled with sugarcane rock candy.

- Bánh gai: made from the leaves of the "gai" tree (Boehmeria nivea) dried, boiled, ground into small pieces, then mixed with glutinous rice, wrapped in banana leaf. The filling is made from a mixture of coconut, mung bean, peanuts, winter melon, sesame, and lotus seeds.

- Bánh cốm: the cake is made from young glutinous rice seeds. The seeds are put into a water pot, stirred on fire, and juice extracted from the pomelo flower is added. The filling is made from steamed mung bean, scraped coconut, sweetened pumpkin, and sweetened lotus seeds.

- Other bánh made from glutinous rice are bánh tro, bánh tét, bánh ú, bánh măng, bánh ít, bánh khúc, bánh tổ, bánh in, bánh dẻo, bánh su sê, bánh nổ...

- Xôi are sweet or savoury dishes made from steamed glutinous rice and other ingredients. Sweet xôi are typically eaten as breakfast. Savoury xôi can be eaten as lunch. Xôi dishes made from glutinous rice include:

- Xôi lá cẩm: made with the magenta plant.

- Xôi lá dứa: made with pandan leaf extract for the green colour and a distinctive pandan flavour.

- Xôi chiên phồng: deep-fried glutinous rice patty

- Xôi gà: made with coconut juice and pandan leaf served with fried or roasted chicken and sausage.

- Xôi thập cẩm: made with dried shrimp, chicken, Chinese sausage, Vietnamese sausage (chả), peanuts, coconut, onion, fried garlic ...

- Other xôi dishes made from glutinous rice include: xôi lạc, xôi lúa, xôi đậu xanh, xôi nếp than, xôi gấc, xôi vò, xôi sắn, xôi sầu riêng, xôi khúc, xôi xéo, xôi cá, xôi vị...

- Chè refers to any traditional Vietnamese sweetened soup or porridge. Though chè can be made using a wide variety of ingredients, some chè dishes made from glutinous rice include:

- Chè đậu trắng: made from glutinous rice and black-eyed peas.

- Chè con ong: made from glutinous rice, ginger root, honey, and molasses.

- Chè cốm: made from young glutinous rice seeds, kudzu flour, and juice from the pomelo flower.

- Chè xôi nước: balls made from mung bean paste in a shell made of glutinous rice flour; served in a thick clear or brown liquid made of water, sugar, and grated ginger root.

- Cơm nếp: glutinous rice that is cooked in the same way as ordinary rice, except that the water used is flavoured by adding salts or by using coconut juice, or soups from chicken broth or pork broth.

- Cơm rượu: Glutinous rice balls cooked and mixed with yeast, served in a small amount of rice wine.

- Cơm lam: Glutinous rice cooked in a tube of bamboo of the genus Neohouzeaua and often served with grilled pork or chicken.

Glutinous rice can also be fermented to make Vietnamese alcoholic beverages, such as rượu nếp, rượu cần and rượu đế.

Cơm lam, rice cooked in a bamboo tube

Xôi gấc, glutinous rice cooked with Gac fruit

Xôi gà or chicken xôi

Bánh giầy, pounded rice cake

Bánh chưng a savoury rice cake with mung beans and pork fillings, usually consumed during Tết

Bánh cốm, made from young glutinous rice paste

Cơm rượu, fermented glutinous rice as dessert

Chè đậu trắng, glutinous rice and black-eyed peas

Bánh gai, made with the paste of boehmeria nivea plant

Beverages[edit]

Non-food uses[edit]

In construction, glutinous rice is a component of sticky rice mortar for use in masonry. Chemical tests have confirmed that this is true for the Great Wall of China and the city walls of Xi'an.[43][44] In Assam also, this rice was used for building palaces during Ahom rule.[citation needed]

Glutinous rice starch may also be used to create wheatpaste, an adhesive material.[45]

See also[edit]

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Rice dice

working at Rice field

Rice Cultivation

2

Rice and wild rice

3

Glutinous rice

4

long grain rice

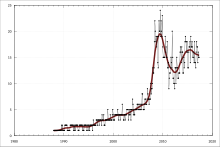

History of rice cultivation

The history of rice cultivation is an interdisciplinary subject that studies archaeological and documentary evidence to explain how rice was first domesticated and cultivated by humans, the spread of cultivation to different regions of the planet, and the technological changes that have impacted cultivation over time.

The current scientific consensus, based on archaeological and linguistic evidence, is that Oryza sativa rice was first domesticated in the Yangtze River basin in South East Asia 13,500 to 8,200 years ago. [1][2][3][4] From that first cultivation, migration and trade spread rice around the world - first to much of east Asia, and then further abroad, and eventually to the Americas as part of the Columbian exchange. The now less common Oryza glaberrima rice was independently domesticated in Africa around 3,000 years ago.[5] Other wild rice species have also been cultivated in different geographies, such as in the Americas.

Since its spread, rice has become a global staple crop important to food security and food cultures around the world. Local varieties of Oryza sativa have resulted in over 40,000 cultivars of various types. More recent changes in agricultural practices and breeding methods as part of the Green Revolution and other transfers of agricultural technologies has led to increased production in recent decades,[6] with emergence of new types such as golden rice, which was genetically engineered to contain beta carotene.

Historyedit

Origins in China

The current scientific consensus, based on archaeological and linguistic evidence, is that rice was first domesticated in the Yangtze River basin in Southern East Asia, aboriginal people of South China who in the 5000 century bce formed a powerful kingdom in present-day Zhejiang and Fujian provinces. .[1][2][3][4] Because the functional allele for nonshattering, the critical indicator of domestication in grains, as well as five other single-nucleotide polymorphisms, is identical in both indica and japonica, Vaughan et al. (2008) determined a single domestication event for O. sativa.[2] This was supported by a genetic study in 2011 that showed that all forms of Asian rice, both indica and japonica, sprang from a single domestication event that occurred 13,500 to 8,200 years ago in China from the wild rice Oryza rufipogon.[8] A more recent population genomic study indicates that japonica was domesticated first, and that indica rice arose when japonica arrived in India about ~4,500 years ago and hybridized with an undomesticated proto-indica or wild O. nivara.[9]

There are two most likely centers of domestication for rice as well as the development of the wetland agriculture technology. The first is in the lower Yangtze River, believed to be the homelands of the pre-Austronesians and possibly also the Kra-Dai , and associated with the Kauhuqiao, Hemudu, Majiabang, Songze, Liangzhu, and Maqiao cultures. , It is characterized by pre-Austronesian features, including stilt houses, jade carving, and boat technologies. Their diet was also supplemented by acorns, water chestnuts, foxnuts, and pig domestication.[4][7][10][11][12]

The second is in the middle Yangtze River, believed to be the homelands of the early Hmong-Mien-speakers and associated with the Pengtoushan, Nanmuyuan, Liulinxi, Daxi, Qujialing, and Shijiahe cultures. Both of these regions were heavily populated and had regular trade contacts with each other, as well as with early Austroasiatic speakers to the west, and early Kra-Dai speakers to the south, facilitating the spread of rice cultivation throughout southern China.[7][10][12]

Rice was gradually introduced north into early Sino-Tibetan Yangshao and Dawenkou culture millet farmers, either via contact with the Daxi culture or the Majiabang-Hemudu culture. By around 4000 to 3800 BC, they were a regular secondary crop among southernmost Sino-Tibetan cultures. It did not replace millet, largely because of different environment conditions in northern China, but it was cultivated alongside millet in the southern boundaries of the millet-farming regions. Conversely, millet was also introduced into rice-farming regions.[7][13]

By the late Neolithic (3500 to 2500 BC), population in the rice cultivating centers had increased rapidly, centered around the Qujialing-Shijiahe culture and the Liangzhu culture. There was also evidence of intensive rice cultivation in paddy fields as well as increasingly sophisticated material cultures in these two regions. The number of settlements among the Yangtze cultures and their sizes increased, leading some archeologists to characterize them as true states, with clearly advanced socio-political structures. The Prehistoric Maritime Frontier of Southeast China : Indigenous Bai Yue and Their Oceanic Dispersal (The Archaeology of Asia-pacific NavigationHowever, it is unknown if they had centralized control.[14][15]

Liangzhu and Shijiahe declined abruptly in the terminal Neolithic (2500 to 2000 BC). With Shijiahe shrinking in size, and Liangzhu disappearing altogether. This is largely believed to be the result of the southward expansion of the early Sino-Tibetan Longshan culture. Fortifications like walls (as well as extensive moats in Liangzhu cities) are common features in settlements during this period, indicating widespread conflict. This period also coincides with the southward movement of rice-farming cultures to the Lingnan and Fujian regions, as well as the southward migrations of the Austronesian, Kra-Dai, and Austroasiatic-speaking peoples to Mainland Southeast Asia and Island Southeast Asia.[14][16][17] A genomic study also indicates that at around this time, a global cooling event (the 4.2 k event) led to tropical japonica rice being pushed southwards, as well as the evolution of temperate japonica rice that could grow in more northern latitudes.[18]

Genomic studies suggests that indica rice arrives in China from India between 2,000 and 1,400 years ago.[18]

Southeast Asia[edit]

The spread of japonica rice cultivation to Southeast Asia started with the migrations of the Austronesian Dapenkeng culture into Taiwan between 3500 and 2000 BC (5,500 BP to 4,000 BP). The Nanguanli site in Taiwan, dated to ca. 2800 BC, has yielded numerous carbonized remains of both rice and millet in waterlogged conditions, indicating intensive wetland rice cultivation and dryland millet cultivation.[10] A multidisciplinary study using rice genome sequences indicate that tropical japonica rice was pushed southwards from China after a global cooling event (the 4.2-kiloyear event) that occurred approximately 4,200 years ago.[18]

From about 2000 to 1500 BC, the Austronesian expansion began, with settlers from Taiwan moving south to colonize Luzon in the Philippines, bringing rice cultivation technologies with them. From Luzon, Austronesians rapidly colonized the rest of Island Southeast Asia, moving westwards to Borneo, the Malay Peninsula and Sumatra; and southwards to Sulawesi and Java. By 500 BC, there is evidence of intensive wetland rice agriculture already established in Java and Bali, especially near very fertile volcanic islands.[10]

It has been speculated the rice did not survive the Austronesian voyages into Micronesia due to the sheer distance of ocean they were crossing and the lack of abundant rain. These voyagers became the ancestors of the Lapita culture. By the time they migrated southwards to the Bismarck Archipelago, they had already lost the technology of rice farming. However, there is no archaeological record of rice in Polynesia and Micronesia before or during the time of Lapita pottery fitting the hypothesis.[19]

Rice, along with other Southeast Asian food plants, were also later introduced to Madagascar, the Comoros, and the coast of East Africa by around the 1st millennium AD by Austronesian settlers from the Greater Sunda Islands.[20]

Much later Austronesian voyages from Island Southeast Asia succeeded in bringing rice to Guam during the Latte Period (AD 900 to AD 1700). Guam is the only island in Oceania where rice was grown in pre-colonial times.[21][22]

Within Mainland Southeast Asia, rice was presumably spread through river trade between the early Hmong-Mien-speakers of the Middle Yangtze basin and the early Kra-Dai-speakers of the Pearl River and Red River basins, as well as the early Austroasiatic-speakers of the Mekong River basin. Evidence for rice cultivation in these regions, dates to slightly later than the Dapenkeng settlement of Taiwan, at around 3000 BC. Southward migrations of the Austroasiatic and Kra-Dai-speakers introduced it into Mainland Southeast Asia. The earliest evidence of rice cultivation in Mainland Southeast Asia come from the Ban Chiang site in northern Thailand (ca. 2000 to 1500 BC); and the An Sơn site in southern Vietnam (ca. 2000 to 1200 BC).[10][23] A genomic study indicates that rice diversified into Maritime Southeast Asia between 2,500 and 1,500 years ago.[18]

Korean peninsula and Japanese archipelago[edit]

Mainstream archaeological evidence derived from paleoethnobotanical investigations indicate dry-land rice was introduced to Korea and Japan sometime between 3500 and 1200 BC. The cultivation of rice then occurred on a small scale, fields were impermanent plots, and evidence shows that in some cases domesticated and wild grains were planted together. The technological, subsistence, and social impact of rice and grain cultivation is not evident in archaeological data until after 1500 BC. For example, intensive wet-paddy rice agriculture was introduced into Korea shortly before or during the Middle Mumun pottery period (circa 850–550 BC) and reached Japan by the final Jōmon or initial Yayoi periods circa 300 BC.[24][25] A genomic study indicates that temperate japonica, which predominates in Korea and Japan, evolved after a global cooling event (the 4.2k event) that occurred 4,200 years ago.[18]

Indian subcontinent[edit]

Evidence for rice consumption in India since 6000BCE is found at Lahuradewa in Uttar Pradesh.[26] However, whether or not the samples at Lahuradewa belong to domesticated rice is still disputed.[27] Rice was cultivated in the Indian subcontinent from as early as 5,000 BC.[28] "Several wild cereals, including rice, grew in the Vindhyan Hills, and rice cultivation, at sites such as Chopani-Mando and Mahagara, may have been underway as early as 7,000 BP. Rice appeared in the Ganges valley regions of northern India as early as 4530 BC and 5440 BC, respectively.[29] The early domestication process of rice in ancient India was based around the wild species Oryza nivara. This led to the local development of a mix of 'wetland' and 'dryland' agriculture of local Oryza sativa var. indica rice agriculture, before the truly 'wetland' rice Oryza sativa var. japonica, arrived around 2000 BC.[30]

Rice was cultivated in the Indus Valley civilization (3rd millennium BC).[31] Agricultural activity during the second millennium BC included rice cultivation in the Kashmir and Harrappan regions.[29] Mixed farming was the basis of Indus valley economy.[31]

O. sativa was recovered from a grave at Susa in Iran (dated to the first century AD) at one end of the ancient world, while at the same time rice was grown in the Po valley in Italy. In northern Iran, in Gilan province, many indica rice cultivars including 'Gerdeh', 'Hashemi', 'Hasani', and 'Gharib' have been bred by farmers.[32]

Africa[edit]

Although Oryza sativa was domesticated in Asia, the now less popular Oryza glaberrima rice was independently domesticated in Africa 3,000 to 3,500 years ago.[5] Between 1500 and 800 BC, Oryza glaberrima propagated from its original centre, the Niger River delta, and extended to Senegal. However, it never developed far from its original region. Its cultivation even declined in favour of the Asian species, which was introduced to East Africa early in the common era and spread westward.[33] Many of the foods enjoyed in North America today were brought over from Africa during the slave trade, including rice. Many Africans were taken from rice-producing regions such as Casamance in South Senegal due to their knowledge of how to cultivate rice. They were then shipped to the Carolinas or Mexico to work on the new rice fields. [34]

Europe[edit]

Rice was known to the Classical world, being imported from Egypt, and perhaps west Asia. It was known to Greece (where it is still cultivated in Macedonia and Thrace) by returning soldiers from Alexander the Great's military expedition to Asia. Large deposits of rice from the first century AD have been found in Roman camps in Germany.[35]

The Moors brought Asiatic rice to the Iberian Peninsula in the 10th century. Records indicate it was grown in Valencia and Majorca. In Majorca, rice cultivation seems to have stopped after the Christian conquest, although historians are not certain.[36]

The Moors may have also brought rice to Sicily, with cultivation starting in the 9th century,[37] where it was an important crop[36] long before it is noted in the plain of Pisa (1468) or in the Lombard plain (1475), where its cultivation was promoted by Ludovico Sforza, Duke of Milan, and demonstrated in his model farms.[38]

After the 15th century, rice spread throughout Italy and then France, later propagating to all the continents during the age of European exploration.

In Russia, a short-grain, starchy rice similar to the Italian varieties, has been grown in the Krasnodar Krai, and known in Russia as "Kuban Rice" or "Krasnodar Rice". In the Russian Far East several japonica cultivars are grown in Primorye around the Khanka Lake. Increasing scale of rice production in the region has recently brought criticism towards growers' alleged bad practices in regard to the environment.

America[edit]

Recent Research indicates that rice was independently domesticated in South America before the 14th century from Amazon wild rice. [39]

Controversies[]

The origin of Oryza sativa rice domestication has been a subject of much debate among those who study crop history and anthropology – whether rice originated in India or China.[40][41] Asian rice, Oryza sativa, is one of oldest crop species. It has tens of thousands of varieties and two major subspecies, japonica and indica. , Archeologists focusing on East and Southeast Asia argue that rice farming began in southern along the Yangtze River and spread to Korea and Japan from there south and northeast.[42][41] Archaeologists working in India argue that rice cultivation started in the valley of the Ganges River[43] and Indus valley,[44] by peoples unconnected to those of the Yangzte.[45][46][41]

A 2012 study, through genome sequencing and mapping of hundreds of rice varieties and that of wild rice populations, indicated that the domestication of rice occurred around the central Pearl River valley region of southern China, in contradiction to archaeological evidence.[47] The study is based on modern distribution maps of wild rice populations which may be potentially inconclusive due to drastic climatic changes that happened during the end of the last glacial period, ca. 12,000 years ago. However, the climate in regions north of the Pearl River would likely be less suitable for this wild rice. Human activity over thousands of years may also have removed populations of wild rice from their previous ranges. Based on Chinese texts, it is speculated there are populations of native wild rice along the Yangtze basin in c. AD 1,000 that have recently become extinct.[13]

An older theory, based on one chloroplast and two nuclear gene regions, Londo et al. (2006) had proposed that O. sativa rice was domesticated at least twice—indica in eastern India, Myanmar, and Thailand; and japonica in southern China and Vietnam—though they concede that archaeological and genetic evidence exist for a single domestication of rice in the lowlands of southern China.[48]

In 2003, Korean archaeologists announced they discovered burnt grains of domesticated rice in Soro-ri, Korea, which dated to 13,000 BC. These antedates the oldest grains found in China, which were dated to 10,000 BC, and potentially challenge the explanation that domesticated rice originated in the Yangtze River basin of China.[49] The findings were received by academia with strong skepticism.[50][51]

Regional history[edit]

Asia[edit]

Today, the majority of all rice produced comes from China, India, Indonesia, Bangladesh, Vietnam, Thailand, Myanmar, Pakistan, Philippines, Korea and Japan. Asian farmers still account for 87% of the world's total rice production. Because so much rice is produced in Bangladesh, it is also the staple food of the country.

Indonesia[edit]

Rice is a staple food for all classes in contemporary Indonesia,[52][53] and it holds the central place in Indonesian culture and Indonesian cuisine: it shapes the landscape; is sold at markets; and is served in most meals. Rice accounts for more than half of the calories in the average diet, and the source of livelihood for about 20 million households. The importance of rice in Indonesian culture is demonstrated through the reverence of Dewi Sri, the rice goddess of ancient Java and Bali.

Evidence of wild rice on the island of Sulawesi dates from 3000 BC. Historic written evidence for the earliest cultivation, however, comes from eighth century stone inscriptions from the central island of Java, which show kings levied taxes in rice. The images of rice cultivation, rice barn, and mice infesting a rice field is evident in Karmawibhangga bas-reliefs of Borobudur. Divisions of labour between men, women, and animals that are still in place in Indonesian rice cultivation, were carved into relief friezes on the ninth century Prambanan temples in Central Java: a water buffalo attached to a plough; women planting seedlings and pounding grain; and a man carrying sheaves of rice on each end of a pole across his shoulders (pikulan). In the sixteenth century, Europeans visiting the Indonesian islands saw rice as a new prestige food served to the aristocracy during ceremonies and feasts.[53]

Nepal[edit]

Rice is the major food amongst all the ethnic groups in Nepal. In the Terai, most rice varieties are cultivated during the rainy season. The principal rice growing season, known as "Berna-Bue Charne", is from June to July when water is sufficient for only a part of the fields; the subsidiary season, known as "Ropai" is from April to September, when there is usually enough water to sustain the cultivation of all rice fields. Farmers use irrigation channels throughout the cultivation seasons.[citation needed]Nepal's food security depends on the production of staple cereals with rice being the main cereal. Rice is grown on 1.49 million ha in Nepal with an average productivity of 3.5 t/ha and total annual production of 5.6 million tons in 2018 (MoALD, 2019).[54]

Philippines[edit]

The Banaue Rice Terraces (Filipino: Hagdan-hagdang Palayan ng Banawe) are 2,000-year-old terraces that were carved into the mountains of Ifugao in the Philippines by the ancestors of the Igorot people. The Rice Terraces are commonly referred to as the "Eighth Wonder of the World".[55][56][57] It is commonly thought that the terraces were built with minimal equipment, largely by hand. The terraces are located approximately 1,500 meters (5,000 ft) above sea level. They are fed by an ancient irrigation system from the rainforests above the terraces. It is said that if the steps were put end to end, it would encircle half the globe.[58] The terraces are found in the province of Ifugao and the Ifugao people have been its caretakers. Ifugao culture revolves[59][better source needed] around rice and the culture displays an elaborate array of celebrations linked with agricultural rites from rice cultivation to rice consumption. The harvest season generally calls for thanksgiving feasts, while the concluding harvest rites called tango or tungul (a day of rest) entails a strict taboo on any agricultural work. Partaking of the bayah (rice beer), rice cakes, and betel nut constitutes an indelible practice during the festivities.

The Ifugao people practice traditional farming spending most of their labor at their terraces and forest lands while occasionally tending to root crop cultivation. The Ifugaos have also[58] been known to culture edible shells, fruit trees, and other vegetables which have been exhibited among Ifugaos for generations. The building of the rice terraces consists of blanketing walls with stones and earth which are designed to draw water from a main irrigation canal above the terrace clusters. Indigenous rice terracing technologies have been identified with the Ifugao's rice terraces such as their knowledge of water irrigation, stonework, earthwork and terrace maintenance. As their source of life and art, the rice terraces have sustained and shaped the lives of the community members.

Sri Lanka[edit]

Rice is the staple food amongst all the ethnic groups in Sri Lanka. Agriculture in Sri Lanka mainly depends on the rice cultivation. Rice production is acutely dependent on rainfall and government supply necessity of water through irrigation channels throughout the cultivation seasons. The principal cultivation season, known as "Maha", is from October to March and the subsidiary cultivation season, known as "Yala", is from April to September. During Maha season, there is usually enough water to sustain the cultivation of all rice fields, nevertheless in Yala season there is only enough water for cultivation of half of the land extent. Traditional rice varieties are now making a comeback with the recent interest in green foods.

Thailand[edit]

Rice is the main export of Thailand, especially white jasmine rice 105 (Dok Mali 105).[60] Thailand has a large number of rice varieties, 3,500 kinds with different characters, and five kinds of wild rice cultivates.[61] In each region of the country there are different rice seed types. Their use depends on weather, atmosphere, and topography.[62]

The northern region has both lowlands and high lands. The farmers' usual crop is non-glutinous rice[62] such as Niew Sun Pah Tong rice. This rice is naturally protected from leaf disease, and its paddy (unmilled rice) (Thai: ข้าวเปลือก) has a brown color.[63] The northeastern region is a large area where farmers can cultivate about 36 million square meters of rice. Although most of it is plains and dry areas,[64] white jasmine rice 105—the most famous Thai rice—can be grown there. White jasmine rice was developed in Chonburi Province first and after that grown in many areas in the country, but the rice from this region has a high quality, because it is softer, whiter, and more fragrant.[65] This rice can resist drought, acidic soil, and alkaline soil.[66]

The central region is mostly composed of plains. Most farmers grow Jao rice.[64] For example, Pathum Thani 1 rice which has qualities similar to white jasmine 105 rice. Its paddy has the color of thatch, and the cooked rice also has fragrant grains.[67]

In the southern region, most farmers transplant around boundaries to the flood plains or on the plains between mountains. Farming in the region is slower than other regions because the rainy season comes later.[64] The popular rice varieties in this area are the Leb Nok Pattani seeds, a type of Jao rice. Its paddy has the color of thatch, and it can be processed to make noodles.[68]

Companion plant[edit]

One of the earliest known examples of companion planting is the growing of rice with Azolla, the mosquito fern, which covers the top of a fresh rice paddy's water, blocking out any competing plants, as well as fixing nitrogen from the atmosphere for the rice to use. The rice is planted when it is tall enough to poke out above the azolla. This method has been used for at least a thousand years.

Middle East[edit]

Rice was grown in some areas of Mesopotamia (southern Iraq). With the rise of Islam, it moved north to Nisibin, the southern shores of the Caspian Sea (in Gilan and Mazanderan provinces of Iran)[32] and then beyond the Muslim world into the valley of the Volga. In Egypt, rice is mainly grown in the Nile Delta. In Palestine, rice came to be grown in the Jordan Valley. Rice is also grown in Saudi Arabia at Al-Ahsa Oasis and in Yemen.[36]

Caribbean and Latin America[edit

Most of the rice used today in the cuisine of the Americas is not native but was introduced to Latin America and the Caribbean by European colonizers at an early date. However, there are at least two native (endemic) species of rice present in the Amazon region of South America, and one or both were used by the indigenous inhabitants of the region to create the domesticated form Oryza sp., some 4000 years ago.[69]

Spanish colonizers introduced Asian rice to Mexico in the 1520s at Veracruz, and the Portuguese and their African slaves introduced it at about the same time to colonial Brazil.[70] Recent scholarship suggests that enslaved Africans played an active role in the establishment of rice in the New World and that African rice was an important crop from an early period.[71] Varieties of rice and bean dishes that were a staple dish along the peoples of West Africa remained a staple among their descendants subjected to slavery in the Spanish New World colonies, Brazil and elsewhere in the Americas.[72]

Chile

Royal Governor Ambrosio O'Higgins was an early proponent of rice cultivation in Chile during his rule between 1788 and 1796.[73] The first rice cultivation occurred however much later, around 1920, yielding mixed results.[73] Various attempts in Central Chile followed, also yielding mixed results.[73] In part, the failure to establish successful rice cultivation in the first attempts is attributed to the indiscriminate use of rice varieties from areas with tropical climate that did not grow well in central Chile's temperate climate.[73] Early rice farmers had scant knowledge of the plant and learned chiefly by trial and error.[73] Years later temperate climate varieties were imported but these ended up being mixed with the previously imported tropical varieties producing seeds that were labelled "semilla nacional".[73] In the 1939–1940 season 13,190 hectares of rice existed in Chile and by this time rice cultivation had become one of the most profitable agricultural businesses in Chile.[73] In 1939 a division of the Ministry of Agriculture begun to study rice cultivated in Chile. This work continued in the research station Estación Genética de Ñuble in the 1940s.[73] Labour opportunities in the rice fields meant a salary increase and a generally improved economic situation for many rural workers.[73] However, as salaries increased between 1940 and 1964 the profitability also decreased.[73] Rice fields also used lands with poor clay-rich soils that were less suitable for other activities.[73] By 1964 38,000 ha of rice were cultivated.[73] Rice was cultivated as far south as the commune San Carlos.[73]

North America[edit]

In 1694, rice arrived in South Carolina, probably originating from Madagascar.[70] Tradition (possibly apocryphal) has it that pirate John Thurber was returning from a slave-trading voyage to Madagascar when he was blown off course and put into Charleston for repairs. While there he gave a bag of seed rice to explorer Dr. Henry Woodward, who planted the rice and experimented with it until finding that it grew exceptionally well in the wet Carolina soil.[75][76]

The mastery of rice farming was a challenge for the English and other European settlers who were unfamiliar with the crop. Native Americans, who mostly gathered wild rice, were also inexperienced with rice cultivation. However, within the first fifty years of settlement rice became the dominant crop in South Carolina.[77]

In the United States, colonial South Carolina and Georgia grew and amassed great wealth from the slave labor obtained from the Senegambia area of West Africa and from coastal Sierra Leone. At the port of Charleston, through which 40% of all American slave imports passed, slaves from this region of Africa brought the highest prices due to their prior knowledge of rice culture, which was put to use on the many rice plantations around Georgetown, Charleston, and Savannah.

From the enslaved Africans, plantation owners learned how to dyke the marshes and periodically flood the fields. At first the rice was laboriously milled by hand using large mortars and

pestles made of wood, then winnowed in sweetgrass baskets (the making of which was another skill brought by slaves from Africa). The invention of the rice mill increased profitability of the crop, and the addition of waterpower for the mills in 1787 by millwright Jonathan Lucas was another step forward.

Rice culture in the southeastern U.S. became less profitable with the loss of slave labor after the American Civil War, and it finally died out just after the turn of the 20th century. Today, people can visit the only remaining rice plantation in South Carolina that still has the original winnowing barn and rice mill from the mid-19th century at the historic Mansfield Plantation in Georgetown, South Carolina. The predominant strain of rice in the Carolinas was from Africa and was known as 'Carolina Gold'. The cultivar has been preserved and there are current attempts to reintroduce it as a commercially grown crop.[78]

In the southern United States, rice has been grown in southern Arkansas, Louisiana, and east Texas since the mid-19th century. Many Cajun farmers grew rice in wet marshes and low-lying prairies where they could also farm crayfish when the fields were flooded.[79] In recent years rice production has risen in North America, especially in the Mississippi embayment in the states of Arkansas and Mississippi (see also Arkansas Delta and Mississippi Delta).

Rice cultivation began in California during the California Gold Rush, when an estimated 40,000 Chinese laborers immigrated to the state and grew small amounts of the grain for their own consumption. However, commercial production began only in 1912 in the town of Richvale in Butte County.[80] By 2006, California produced the second-largest rice crop in the United States,[81] after Arkansas, with production concentrated in six counties north of Sacramento.[82] Unlike the Arkansas–Mississippi Delta region, California's production is dominated by short- and medium-grain japonica varieties, including cultivars developed for the local climate such as Calrose, which makes up as much as 85% of the state's crop.[83]

References to "wild rice" native to North America are to the unrelated Zizania palustris.[84]

More than 100 varieties of rice are commercially produced primarily in six states (Arkansas, Texas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, and California) in the U.S.[85] According to estimates for the 2006 crop year, rice production in the U.S. is valued at $1.88 billion, approximately half of which is expected to be exported. The U.S. provides about 12% of world rice trade.[85] The majority of domestic utilization of U.S. rice is direct food use (58%), while 16% is used in each of processed foods and beer. 10% is found in pet food.[85]

Oceania[edit]

Rice was one of the earliest crops planted in Australia by British settlers, who had experience with rice plantations in the Americas and India.

Although attempts to grow rice in the well-watered north of Australia have been made for many years, they have consistently failed because of inherent iron and manganese toxicities in the soils and destruction by pests.

In the 1920s, it was seen as a possible irrigation crop on soils within the Murray–Darling basin that were too heavy for the cultivation of fruit and too infertile for wheat.[86]

Because irrigation water, despite the extremely low runoff of temperate Australia,[87] was (and remains) very cheap, the growing of rice was taken up by agricultural groups over the following decades. Californian varieties of rice were found suitable for the climate in the Riverina,[86] and the first mill opened at Leeton in 1951.

Even before this Australia's rice production greatly exceeded local needs,[86] and rice exports to Japan have become a major source of foreign currency. Above-average rainfall from the 1950s to the middle 1990s[88] encouraged the expansion of the Riverina rice industry, but its prodigious water use in a practically waterless region began to attract the attention of environmental scientists. These became severely concerned with declining flow in the Snowy River and the lower Murray River.

Although rice growing in Australia is highly profitable due to the cheapness of land, several recent years of severe drought have led many to call for its elimination because of its effects on extremely fragile aquatic ecosystems. The Australian rice industry is somewhat opportunistic, with the area planted varying significantly from season to season depending on water allocations in the Murray and Murrumbidgee irrigation regions.

Australian Aboriginal people have harvested native rice varieties for thousands of years, and there are ongoing efforts to grow commercial quantities of these species.[89][90]

References[edit]

- ^ a b Normile, Dennis (1997). "Yangtze seen as earliest rice site". Science. 275 (5298): 309–310. doi:10.1126/science.275.5298.309. S2CID 140691699.

- ^ a b c Vaughan, DA; Lu, B; Tomooka, N (2008). "The evolving story of rice evolution". Plant Science. 174 (4): 394–408. doi:10.1016/j.plantsci.2008.01.016.

- ^ a b Harris, David R. (1996). The Origins and Spread of Agriculture and Pastoralism in Eurasia. Psychology Press. p. 565. ISBN 978-1-85728-538-3.

- ^ a b c Zhang, Jianping; Lu, Houyuan; Gu, Wanfa; Wu, Naiqin; Zhou, Kunshu; Hu, Yayi; Xin, Yingjun; Wang, Can; Kashkush, Khalil (December 17, 2012). "Early Mixed Farming of Millet and Rice 7800 Years Ago in the Middle Yellow River Region, China". PLOS ONE. 7 (12): e52146. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...752146Z. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0052146. PMC 3524165. PMID 23284907.

- ^ a b Choi, Jae Young (March 7, 2019). "The complex geography of domestication of the African rice Oryza glaberrima". PLOS Genetics. 15 (3): e1007414. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1007414. PMC 6424484. PMID 30845217.

- ^ "Is basmati rice healthy?". K-agriculture. April 4, 2023.

- ^ a b c d He, Keyang; Lu, Houyuan; Zhang, Jianping; Wang, Can; Huan, Xiujia (June 7, 2017). "Prehistoric evolution of the dualistic structure mixed rice and millet farming in China". The Holocene. 27 (12): 1885–1898. Bibcode:2017Holoc..27.1885H. doi:10.1177/0959683617708455. S2CID 133660098.

- ^ Molina, J.; Sikora, M.; Garud, N.; Flowers, J. M.; Rubinstein, S.; Reynolds, A.; Huang, P.; Jackson, S.; Schaal, B. A.; Bustamante, C. D.; Boyko, A. R.; Purugganan, M. D. (2011). "Molecular evidence for a single evolutionary origin of domesticated rice". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 108 (20): 8351–6. Bibcode:2011PNAS..108.8351M. doi:10.1073/pnas.1104686108. PMC 3101000. PMID 21536870.

- ^ Choi, Jae; et al. (2017). "The Rice Paradox: Multiple Origins but Single Domestication in Asian Rice". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 34 (4): 969–979. doi:10.1093/molbev/msx049. PMC 5400379. PMID 28087768.

- ^ a b c d e f Bellwood, Peter (December 9, 2011). "The Checkered Prehistory of Rice Movement Southwards as a Domesticated Cereal—from the Yangzi to the Equator" (PDF). Rice. 4 (3–4): 93–103. doi:10.1007/s12284-011-9068-9. S2CID 44675525. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 24, 2019. Retrieved January 24, 2019.