Lịch sử Trung Á

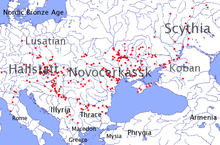

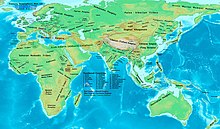

Pic: Steppe Region - steppe belt (turquoise) Turk, Persia, Mongolia, Russian, Khitan, Tartar: Eurasian Liên minh văn minh du mục và bán nông nghiệp

Pic: Steppe Region - steppe belt (turquoise) Turk, Persia, Mongolia, Russian, Khitan, Tartar: Eurasian Liên minh văn minh du mục và bán nông nghiệp

Hình: Vòng đai màu xanh ngọc bích là vùng thảo nguyên của dân du mục, sau này tạo thành con đường buôn bán tơ lụa, trầm hương và gia vị từ Trung Á sang Đông Á và đi tới Đông Nam Á

Mete Han and the Xiongnu Legacy | Historical Turkic States

Mete Han và Di sản Hung Nô

https://youtu.be/cubsSWp3RYY

Were the Xiongnu of the Eurasian Steppe Huns, Turks, Iranic or Mongolic?

Có phải Người Hung Nô của thảo nguyên Âu-Á là Huns/Hung, Turk/Thổ, Iran/Ba Tư hay Mongol/Mông Cổ không vậy?

https://youtu.be/2bADrmFCuwE

Lịch sử Trung Á chịu sự tác động vào khí hậu và địa lý khu vực. Tính chất khô cằn của khu vực này gây khó khăn cho nông nghiệp trong khi việc không giáp biển đã hạn chế các tuyến thương mại. Vì thế, hầu như không có đô thị lớn hình thành trong khu vực. Các tộc người du mục thảo nguyên đã thống trị khu vực này suốt một thiên niên kỷ.

Quan hệ giữa những người du mục thảo nguyên và những người định cư trong và xung quanh khu vực Trung Á mang đậm nét xung đột. Các lối sống du canh du cư cũng phù hợp với chiến tranh, và các tay đua ngựa thảo nguyên đã trở thành một trong những đội quân thiện chiến nhất trên thế giới nhờ các kỹ thuật tàn phá và kỹ năng kỵ binh cung thủ của họ.[1] Trong một số thời kỳ, các lãnh đạo bộ tộc hoặc sự thay đổi điều kiện lại tổ chức một số bộ tộc lại thành một lực lượng quân sự thống nhất và thường xuyên phát động các chiến dịch chinh phục, đặc biệt là vào các khu vực "văn minh" hơn. Một vài kiểu liên minh bộ tộc như vậy bao gồm cuộc xâm lược của người Hung vào châu Âu, cuộc di cư của các bộ tộc người Turk khác nhau vào Transoxiana, các cuộc tấn công các tộc người Ngũ Hồ vào Trung Quốc và đặc biệt là cuộc chinh phục của người Mông Cổ vào các lục địa Á-Âu.

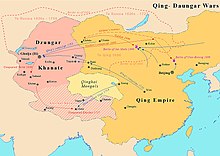

Sự thống trị của những người du mục đã kết thúc vào thế kỷ XVI khi hỏa khí cho phép các thế lực thực dân giành quyền kiểm soát khu vực. Đế quốc Nga, nhà Thanh, và các thế lực khác bành trướng vào khu vực và chiếm đóng phần lớn Trung Á vào cuối thế kỷ XIX. Sau Cách mạng Nga năm 1917, Liên Xô đã hợp nhất phần lớn Trung Á. Các khu vực Trung Á của thuộc Liên Xô đã công nghiệp hóa mạnh mẽ và xây dựng kết cấu hạ tầng, song các nền văn hóa địa phương đã bị kiềm chế và tạo ra một di sản lâu dài những căng thẳng sắc tộc và vấn đề môi trường.

Sau khi Liên Xô sụp đổ vào năm 1991, năm quốc gia Trung Á gồm Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Kyrgyzstan và Tajikistan đã giành được độc lập. Trong tất cả các quốc gia mới này, các cựu quan chức Đảng Cộng sản vẫn nắm quyền, tạo thành các thế lực địa phương.

Thời Cổ đại[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

Trong thiên niên kỷ thứ hai và thứ nhất trước Công nguyên, một loạt các nhà nước lớn và mạnh đã phát triển ở ngoại vi phía nam của Trung Á. Các đế quốc này đã nỗ lực chinh phục các bộ tộc thảo nguyên, nhưng chỉ thu được một số thành công không trọn vẹn. Đế quốc Media và Nhà Achaemenes đã cai trị các khu vực Trung Á. Có thể coi Đế quốc Hung Nô (209 TCN - 93 (hoặc 156) CN) là đế quốc Trung Á đầu tiên thiết lập một ví dụ cho các đế quốc Göktürk (Đột Quyết) và Mông Cổ sau này.[2] Các bộ tộc Bắc Địch tổ tiên của Hung Nô thành lập nhà nước Trung Sơn (khoảng thế kỷ thứ VI TCN -.. khoảng năm 296 TCN) ở tỉnh Hà Bắc, Trung Quốc. Các tước hiệu Thiền vu từng được các đấng cai trị Hung Nô trước thiền vu Mặc Đốn sử dụng, do đó có thể nói rằng lịch sử trở thành nhà nước của Hung Nô bắt đầu từ lâu trước khi Mặc Đốn cai trị.

Tiếp nối thành công của cuộc Chiến tranh Hán-Hung Nô, các quốc gia Trung Quốc thường xuyên cố gắng bành trướng quyền lực của họ về phía tây. Mặc dù có sức mạnh quân sự, song các nhà nước Trung Quốc thấy khó có thể chinh phục toàn bộ khu vực.

Khi đối mặt với một lực lượng mạnh hơn, những người du mục có thể chỉ đơn giản rút lui sâu vào thảo nguyên và chờ đợi cho những kẻ xâm lược rời đi. Vì không có các thành phố và không có tài sản gì ngoài các đàn gia súc mà họ có thể mang đi cùng với mình, những người du mục không có gì để bị buộc phải bảo vệ. Một ví dụ về điều này là ghi chép chi tiết của Herodotus về chiến dịch vô ích của người Ba Tư đối với người Scythia. Những người Scythia, giống như hầu hết các đế chế du mục, đã định cư lâu dài với các quy mô khác nhau, đại diện cho các mức độ khác nhau của nền văn minh.[3] Các khu vực định cư kiên cố ở Kamenka trên sông Dnepr, bắt đầu hình thành từ cuối thế kỷ V TCN, đã trở thành trung tâm của vương quốc Scythia dưới sự cai trị của Ateas, người đã thiệt mạng trong cuộc chiến chống lại Philippos II của Macedonia vào năm 339 TCN.[4]

Một số đế chế, chẳng hạn như các đế quốc Ba Tư và Macedonia, đã xâm nhập sâu vào Trung Á bằng việc lập nên các thành phố và giành quyền kiểm soát những trung tâm thương mại. Các cuộc chinh phục của Alexander Đại đế đã giúp cho nền văn minh Hy Lạp cổ đại bành trướng đến tận Alexandria Eschate (nghĩa đen là "Alexandria xa nhất"), thành lập vào năm 329 TCN ở Tajikistan ngày nay. Sau khi Alexander mất năm 323 TCN, lãnh thổ Trung Á của ông rơi vào tay đế quốc Seleucid trong các cuộc chiến tranh Diadochi.

Năm 250 TCN, phần Trung Á của đế quốc Seleucid (Bactria) ly khai thành Vương quốc Hy Lạp-Bactria, và nước này có quan hệ rộng rãi với Ấn Độ và Trung Quốc cho đến khi nó diệt vong năm 125 TCN. Vương quốc Ấn-Hy Lạp, chủ yếu đóng ở khu vực Punjab ngày nay nhưng kiểm soát một phần khá rộng Afghanistan ngày nay, là nhà nước tiên phong trong phát triển Phật giáo Hy Lạp. Các Vương quốc Kushan (Quý Sương) đã phát triển mạnh trên một vùng rộng lớn của khu vực từ thế kỷ II TCN đến thế kỷ IV, và tiếp tục các truyền thống Hy Lạp và Phật giáo. Các nhà nước này đã phát triển thịnh vượng tại lãnh địa của họ dọc theo con đường tơ lụa nối liền Trung Quốc và châu Âu.

Tương tự như vậy, ở miền đông Trung Á, nhà Hán ở Trung Quốc ở thời kỳ hùng mạnh nhất đã bành trướng tới khu vực. Vào khoảng từ năm 115-60 TCN, quân Hán đã giao chiến với quân Hung Nô để giành quyền kiểm soát các thành bang ốc đảo ở lòng chảo Tarim. Nhà Hán cuối cùng đã thắng và thành lập Tây Vực đô hộ phủ vào năm 60 TCN để cai trị khu vực này.[5][6][7][8] Sau đó, các vương quốc Kushan và đế quốc Hephthalite (Áp Đạt) đã nối tiếp thay thế nhà Hán ở khu vực này.

Sau đó, các thế lực bên ngoài như Đế quốc Sassanid đã đến và thống trị khu vực. Một trong những thế lực đó là Đế chế Parthia có nguồn gốc từ Trung Á, nhưng đã tiếp thu các truyền thống văn hóa Ba Tư-Hy Lạp. Đây là ví dụ đầu tiên về một chủ đề định kỳ của lịch sử Trung Á: Thỉnh thoảng người dân du mục xuất xứ Trung Á lại chinh phục các vương quốc và đế quốc xung quanh, nhưng để rồi nhanh chóng nhập vào nền văn hóa của các dân tộc bị chinh phục.

Tại thời kỳ này, Trung Á là một khu vực không đồng nhất với một hỗn hợp các nền văn hóa và tôn giáo. Phật giáo vẫn là tôn giáo lớn nhất, nhưng tập trung ở phía đông. Xung quanh Ba Tư, Bái Hỏa giáo trở nên quan trọng. Kitô giáo Nestorian truyền tới khu vực, nhưng chỉ trở thành tín ngưỡng dân tộc thiểu số. Ma Ni giáo thành công hơn, trở thành tín ngưỡng lớn thứ ba ở khu vực. Nhiều người Trung Á theo đồng thời hơn một tín ngưỡng, và gần như tất cả các tôn giáo địa phương được truyền cùng với các truyền thống bái vật giáo địa phương.

Các tộc người Turk bắt đầu thâm nhập khu vực vào thế kỷ VI, và cùng với đế chế Göktürk (Đột Quyết), các bộ tộc người Turk nhanh chóng tiến về phía tây và tỏa ra khắp khu vực Trung Á. Những người Uyghur nói tiếng Turk là một trong nhiều nhóm văn hóa riêng biệt nhập lại với nhau thông qua thương mại dọc theo con đường tơ lLụa tại Turfan, sau đó chịu sự cai trị của nhà Đường từ Trung Quốc. Những người Uyghur, chủ yếu là dân du mục chăn nuôi gia súc, đã tiếp thu một số tôn giáo trong đó có Ma Ni giáo, Phật giáo và Kitô giáo dòng Nestorian. Nhiều đồ tạo tác từ thời kỳ này đã được phát hiện trong thế kỷ XIX tại vùng hoang mạc xa xôi này.

Thời Trung cổ[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

Dưới thời nhà Tùy và nhà Đường, Trung Quốc đã bành trướng sang phía đông Trung Á. Chính sách đối ngoại của Trung Quốc đối với phía bắc và phía tây thời bây giờ là đối phó với những tộc người Turk du mục, những tộc người chiếm ưu thế nhất ở Trung Á lúc ấy.[9][10] Để xử lý và tránh mọi mối đe dọa từ các tộc người Turk, nhà Tùy đã một mặt gia cố thành quách mặt khác tiếp các đoàn thương gia và cống nạp của người Turk.[11] Nhà Tùy đã gả công chúa cho các lãnh đạo cộng đồng người Turk, tổng cộng bốn người vào các năm 597, 599, 614, và 617. Nhà Tùy cũng thực hiện chính sách chia rẽ và kích động các nhóm dân tộc chống lại người Turk.[12][13]

Ngay từ thời nhà Tùy, các tộc người Turk đã trở thành lực lượng quân sự lớn trong quân đội Trung Quốc. Khi người Khiết Đan bắt đầu đánh phá miền đông bắc Trung Quốc năm 605, một vị tướng người Hán đã dẫn 2 vạn quân người Turk đi đánh trả, cướp gia súc và phụ nữ của người Khiết Đan làm phần thưởng cho quân lính.[14] Hai lần giữa năm 635 và 636, nhà Đường đã gả công chúa cho các tướng lĩnh người Turk đầu quân trong quân đội nhà Đường.[13]

Trong suốt thời nhà Đường cho đến khi kết thúc 755, đã có khoảng mười tướng người Turk đầu quân cho nhà Đường.[15][16] Trong khi hầu quân nhà Đường là người Hán, thì phần lớn các quân do tướng các tướng người Turk chỉ huy lại không phải là người Hán và họ chủ yếu đóng quân ở biên giới phía tây, nơi quân lính người Hán rất it.[17] Một số đơn vị quân "người Turk" thực ra lại là người Hán du mục hóa, một hiện tượng "khử Hán hóa".[18]

Nội chiến ở Trung Quốc đã gần như hoàn toàn giảm vào năm 626, cùng với sự thất bại tại Ordos vào năm 628 của cuộc khởi nghĩa Lương Sư Đô; sau khi những xung đột nội bộ bị dập tắt, nhà Đường bắt đầu phát động một cuộc tấn công chống lại người Turk.[19] Năm 630, quân nhà Đường quân đội đã chiếm được khu vực hoang mạc Ordos, ở tỉnh Nội Mông và phía Nam Mông Cổ ngày nay, từ người Turk.[14][20]

Sau chiến thắng quân sự này, Đường Thái Tông được nhiều tộc người Turk khác nhau trong khu vực tôn là Đại Hãn và cam kết trung thành. Ngày 11 tháng 6 năm 631, Đường Thái Tông cũng gửi sứ giả đến Xueyantuo (Tiết Diên Đà) mang theo vàng và lụa để thuyết phục thả các tù nhân người Hán bị bắt làm nô lệ - những người bị bắt trong thời kỳ chuyển tiếp từ nhà Tùy sang nhà Đường ở vùng tiền tuyến phía Bắc; sứ đoàn này đã thành công trong việc giải phóng 80.000 nam nữ người Hán để trở về Trung Quốc.[21][22]

Trong khi người Turk đã định cư tại các khu vực hoang mạc Ordos (lãnh thổ cũ của Hung Nô), nhà Đường đã thực hiện chính sách quân sự thống trị vùng thảo nguyên trung tâm. Giống như nhà Hán trước đó, nhà Đường cùng với các đồng minh người Turk như người Uyghur, đã chinh phục Trung Á trong thập niên 640 và 650.[11] Dưới triều Đường Thái Tông, các chiến dịch lớn đã được tiến hành không chỉ nhằm vào Göktürk (Đột Quyết), mà còn các chiến dịch riêng biệt chống lại Tuyuhun (Thổ Dục Hồn) và Xueyantuo. Đường Thái Tông cũng đã phát động chiến dịch chống lại các bang ốc đảo ở lòng chảo Tarim, bắt đầu bằng sự thôn tính Qara-hoja (Cao Xương) năm 640.[23] Vương quốc lân cận Karasahr đã bị nhà Đường thôn tính vào năm 644 và tiếp sau đó là vương quốc Kucha (Quy Từ) bị chinh phục năm 649.[24]

Công cuộc bành trướng sang Trung Á của nhà Đường được tiếp tục dưới triều Đường Cao Tông, người đã xâm chiếm lãnh địa của các tộc người Turk phía Tây lúc đó do Khắc hãn Ashina Helu cai trị vào năm 657.[24] Ashina đã bị đánh bại và khaganate được sáp nhập vào đế quốc Đường.[25] Các lãnh thổ mới này được cai trị thông qua An Tây Đô hộ phủ và bốn đơn vị đồn trú của An Tây. Bá quyền nhà Đường đã vượt qua dãy núi Pamir ở Tajikistan và Afghanistan ngày nay và chỉ bị chặn lại bởi cuộc nổi dậy của người Turk, nhưng nhà Đường vẫn duy trì được sự hiện diện quân sự ở Tân Cương. Tuy nhiên, Tân Cương sau đó bị Thổ Phồn (Tây Tạng) từ phía Nam xâm chiếm vào năm 670. Sau thời điểm ấy, lòng chảo Tarim nằm dưới sự kiểm soát lúc thì của nhà Đường lúc thì của Thổ Phồn (Tây Tạng), những thế lực lớn tranh giành nhau kiểm soát Trung Á lúc đó.[26]

Cuộc cạnh tranh giữa nhà Đường và Thổ Phồn thỉnh thoảng được giải quyết bằng liên minh hôn nhân như cuộc kết hôn giữa công chúa Văn Thành (mất năm 680) với Songtsän Gampo (Tùng Tán Cán Bố).[27][28] Một truyền thống Tây Tạng cho rằng sau khi Songtsän Gampo mất năm 649, quân nhà Đường đã đánh chiếm Lhasa.[29] Học giả Tây Tạng Tsepon W. D. Shakabpa tin rằng điều này không phải sự thật và rằng "những báo cáo lịch sử về sự xuất hiện của quân đội Trung Quốc là không chính xác" và tuyên bố rằng sự kiện như thế không được nhắc đến trong biên niên sử Trung Quốc cũng không phải trong ghi chép của Đôn Hoàng.[30]

Đã có một loạt các cuộc xung đột giữa Thổ Phồn ở lòng chảo Tarim trong các năm 670-692 và 763. Người Tây Tạng thậm chí chiếm được kinh đô Tràng An của nhà Đường trong 15 ngày trong Loạn An Sử.[31][32] Trong thực tế, chính trong cuộc nổi dậy này, nhà Đường đã phải rút các đơn vị đồn trú phía tây của mình đóng quân ở khu vực Cam Túc và Thanh Hải ngày nay, và người Tây Tạng sau đó đã chiếm đóng khu vực này cùng với khu vực mà nay là Tân Cương.[33] Sự thù địch giữa nhà Đường và Thổ Phồn kéo dài cho đến khi một hiệp ước hòa bình chính thức được ký kết vào năm 821.[34] Các điều khoản của hiệp ước này, bao gồm cả biên giới cố định giữa hai nước, được ghi lại bằng hai thứ tiếng trên một cột đá bên ngoài chùa Jokhang ở Lhasa.[35]

Trong thế kỷ VII, Islam giáo bắt đầu xâm nhập khu vực. Những người Ả Rập du mục sa mạc đã đánh bạt những người du mục của thảo nguyên, và đế chế Ả Rập đầu tiên đã giành các khu vực Trung Á. Các cuộc chinh phục đầu tiên dưới sự chỉ huy của Qutayba ibn Muslim (705-715) đã bị chặn lại bởi sự kết hợp giữa các cuộc nổi dậy của các dân tộc tại chỗ và cuộc xâm lược của người Turgesh, nhưng sự sụp đổ của khắc hãn Turgesh sau năm 738 đã mở đường cho việc tái áp đặt của chính quyền Islam giáo dưới thời Nasr ibn Sayyar.

Cuộc xâm lược quân Ả Rập đã đẩy lùi ảnh hưởng của Trung Quốc khỏi miền Tây Trung Á. Trong trận Talas năm 751, một đội quân Ả Rập đánh bại hoàn toàn lực lượng nhà Đường, và trong nhiều thế kỷ tiếp theo các thế lực Trung Đông đã thống trị khu vực này. Tuy nhiên, Islam giáo hóa ồ ạt chỉ bắt đầu từ thế kỷ IX, cùng lúc với sự phân chia quyền lực chính trị của Abbasid và sự xuất hiện của các triều đại Iran và Turk địa phương chẳng hạn như Vương triều Samanid.

Thời kỳ các đế quốc thảo nguyên[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

Các dân tộc thảo nguyên đã nhanh chóng thống trị Trung Á, buộc các thành bang và vương quốc chia cắt phải cống nộp nếu không sẽ bị hủy diệt. Tuy nhiên, năng lực quân sự của các dân tộc thảo nguyên bị hạn chế bởi tính thiếu cấu trúc chính trị trong các bộ lạc. Thỉnh thoảng, các nhóm lại liên hiệp lại dưới sự lãnh đạo của một đại hãn (khan). Khi số lượng lớn của dân du mục liên minh với nhau, sức mạnh và sức tàn phá của họ tăng lên, giống như khi người Hung Nô tấn công Tây Âu. Tuy nhiên, theo truyền thống các lãnh địa chinh phục được được chia cho các con trai của khan, vì thế, những đế chế này thường suy giảm cũng nhanh như khi chúng hình thành.

Khi các cường quốc nước ngoài bị trục xuất, một số đế quốc bản địa đã hình thành ở Trung Á. Các đế quốc Hephthalite là các thế lực mạnh nhất trong số các nhóm du mục tại thế kỷ VI và VII và kiểm soát phần lớn khu vực. Trong thế kỷ X và XI khu vực bị phân chia giữa một số quốc gia hùng mạnh bao gồm Vương triều Samanid của người Turk Seljuk và Đế quốc Khwarezmid.

Khi Thành Cát Tư Hãn thống nhất các bộ tộc Mông Cổ, sức mạnh Trung Á đã vượt xa ra ngoài phạm vi khu vực. Sử dụng kỹ thuật quân sự cao cấp, đế quốc Mông Cổ đã bánh trường và thâu tóm Trung Á và Trung Quốc và bộ phận lớn Nga, và Trung Đông. Sau khi Thành Cát Tư Hãn chết năm 1227, hầu hết Trung Á tiếp tục bị chi phối bởi người kế thừa ông ở đây - hãn quốc Chagatai (Sát Hợp Đài). Trạng thái này chỉ tồn tại trong thời gian ngắn, khi năm 1369 Timur, một nhà lãnh đạo gốc Turk trong truyền thống quân sự Mông Cổ, đã chinh phục hầu hết các khu vực.

Duy trì sự tồn tại của một đế quốc thảo nguyên còn không khó bằng cai trị các vùng đất chinh phục được bên ngoài khu vực. Trong khi các dân tộc thảo nguyên Trung Á thấy việc chinh phục của các khu vực bên ngoài này dễ dàng, họ lại thấy gần như không thể chi phối chúng. Các cơ cấu chính trị lan tỏa của các liên minh thảo nguyên khó được chấp nhận thành nhà nước phức tạp của các dân tộc tại chỗ ở nơi họ đến chiếm đóng. Hơn nữa, quân đội của những người du mục dựa trên số lượng lớn ngựa, thường là ba hoặc bốn con cho mỗi chiến binh. Duy trì các lực lượng này cần những vùng đất chăn thả rộng lớn, mà rất khó có bên ngoài thảo nguyên. Mỗi thời gian dài xa quê hương như vậy sẽ làm cho các đội quân thảo nguyên dần dần tan rã. Để cai trị các dân tộc tại chỗ, các dân tộc thảo nguyên đã buộc phải dựa vào chính quyền địa phương, một yếu tố dẫn đến sự đồng hóa nhanh chóng của những người du mục vào nền văn hóa của những người mà họ đã chinh phục. Một hạn chế quan trọng nữa là quân đội, hầu như không thể xâm nhập vào khu vực phía bắc đầy rừng; do đó, các nhà nước như Novgorod và Muscovy bắt đầu trỗi dậy.

Trong thế kỷ XIV phần lớn Trung Á, và nhiều khu vực ngoài Trung Á, bị Timur (1336-1405), người mà phương Tây gọi là Tamerlane, chinh phục. Chính dưới triều Timur, các nền văn hóa du mục thảo nguyên Trung Á hợp nhất với văn hóa ổn định của Ba Tư (Iran). Một trong những hệ quả của nó là một ngôn ngữ hình ảnh hoàn toàn mới tôn vinh Timur và các đấng cai trị kế tục Timur. ngôn ngữ hình ảnh này cũng được sử dụng để trình bày rõ cam kết của họ với Islam giáo.[36] Tuy nhiên, đế chế rộng lớn của Timur sụp đổ ngay sau khi ông chết. Khu vực này sau đó bị phân chia giữa một loạt các hãn quốc nhỏ hơn, bao gồm cả các hãn quốc Khiva, hãn quốc Bukhara, hãn quốc Kokand, và hãn quốc Kashgar.

Xem thêm[sửa | sửa mã nguồn ]

- Lịch sử Mông Cổ

- Lịch sử Trung Quốc

- Lịch sử Tân Cương

- Lịch sử Kazakhstan

- Lịch sử Uzbekistan

- Lịch sử Turkmenistan

- Lịch sử Kyrgyzstan

- Lịch sử Tajikistan

- Lịch sử Afghanistan

Tham khảo[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

- ^ O'Connell, Robert L.: "Soul of the Sword.", page 51. The Free Press, New York, 2002

- ^ Christoph Baumer "The History of Central Asia – The Age of the Silk Roads (Volume 2); PART I: EARLY EMPIRES AND KINGDOMS IN EAST CENTRAL ASIA 1. The Xiongnu, the First Steppe Nomad Empire"

- ^ Herodotus, IV, 83–144

- ^ “Central Asia, history of”, Encyclopædia Britannica, 2002

- ^ Di Cosmo (2002), tr. 250–251

- ^ Yü (1986), tr. 390–391, 409–411

- ^ Chang (2007), tr. 174

- ^ Loewe (1986), tr. 198

- ^ Ebrey, Walthall & Palais (2006), tr. 113

- ^ Xue (1992), tr. 149–152, 257–264

- ^ a b Ebrey, Walthall & Palais (2006), tr. 92

- ^ Benn (2002), tr. 2–3

- ^ a b Cui (2005), tr. 655–659

- ^ a b Ebrey (1999), tr. 111

- ^ Xue (1992), tr. 788

- ^ Twitchett (2000), tr. 125

- ^ Liu (2000), tr. 85–95

- ^ Gernet (1996), tr. 248

- ^ Xue (1992), tr. 226–227

- ^ Xue (1992), tr. 380–386

- ^ Benn (2002), tr. 2

- ^ Xue (1992), tr. 222–225

- ^ Twitchett, Denis; Wechsler, Howard J. (1979). “Kao-tsung (reign 649-83) and the Empress Wu: The Inheritor and the Usurper”. Trong Denis Twitchett; John Fairbank (biên tập). The Cambridge History of China, Volume 3: Sui and T'ang China Part I. Cambridge University Press. tr. 228. ISBN 978-0-521-21446-9.

- ^ a b Skaff, Jonathan Karem (2009). Nicola Di Cosmo (biên tập). Military Culture in Imperial China. Harvard University Press. tr. 183–185. ISBN 978-0-674-03109-8.

- ^ Skaff, Jonathan Karam (2012). Sui-Tang China and Its Turko-Mongol Neighbors: Culture, Power, and Connections, 580–800. Oxford University Press. tr. 190. ISBN 978-0-19-973413-9.

- ^ Millward, James A. (2007). Eurasian Crossroads: A History of Xinjiang. Columbia University Press. tr. 33–42. ISBN 978-0-231-13924-3.

- ^ Whitfield (2004), tr. 193

- ^ Sen (2003), tr. 24, 30–31

- ^ Charles Bell (1992), Tibet Past and Present , Motilal Banarsidass Publ., tr. 28, ISBN 81-208-1048-1, truy cập ngày 17 tháng 7 năm 2010

- ^ W. D. Shakabpa, Derek F. Maher (2010), One hundred thousand moons, Volume 1 , BRILL, tr. 123, ISBN 90-04-17788-4, truy cập ngày 6 tháng 7 năm 2011

- ^ Beckwith (1987), tr. 146

- ^ Stein (1972), tr. 65

- ^ Twitchett (2000), tr. 109

- ^ Benn (2002), tr. 11

- ^ Richardson (1985), tr. 106–143

- ^ [1] A Journey of a Thousand Years

Nomadic empire

Nomadic empires, sometimes also called steppe empires, Central or Inner Asian empires, were the empires erected by the bow-wielding, horse-riding, nomadic people in the Eurasian Steppe, from classical antiquity (Scythia) to the early modern era (Dzungars). They are the most prominent example of non-sedentary polities.

Some nomadic empires consolidated by establishing a capital city inside a conquered sedentary state and then exploiting the existing bureaucrats and commercial resources of that non-nomadic society. In such a scenario, the originally nomadic dynasty may become culturally assimilated to the culture of the occupied nation before it is ultimately overthrown.[2] Ibn Khaldun (1332–1406) described a similar cycle on a smaller scale in 1377 in his Asabiyyah theory.

Historians of the early medieval period may refer to these polities as "khanates" (after khan, the title of their rulers). After the Mongol conquests of the 13th century the term orda ("horde") also came into use — as in "Golden Horde".

Background

In the history of Central Plain of East Asian polities relied on horses to resist nomadic incursions into their territories, but was only able to purchase the needed horses from the nomads. Trading in horses actually gave these nomadic groups the means to acquire goods by commercial means and reduced the number of attacks and raids into the territories of Central Plain regimes.

Nomads were generally unable to hold onto conquered territories for long without reducing the size of their cavalry forces because of the limitations of pasture in a settled lifestyle. Therefore, settled civilizations usually became reliant on nomadic ones to provide the supply of horses as needed—because they did not have resources to maintain these numbers of horses themselves.[3]

Camel-oriented Bedouin societies in Arabia have functioned as desert-based analogues of Central-Asian horse-oriented nomadic empires.[4]

History[edit]

Ancient history[edit]

Cimmeria[edit]

The Cimmerians were an ancient Indo-European people living north of the Caucasus and the Sea of Azov as early as 1300 BCE until they were driven southward by the Scythians into Anatolia during the 8th century BCE. Linguistically they are usually regarded as Iranian, or possibly Thracian with an Iranian ruling class.

- The Pontic–Caspian steppe: southern Russia and Ukraine until 7th century BCE.

- The northern Caucasus area, including Georgia and modern day Azerbaijan

- Central, East and North Anatolia 714–626 BCE.

Scythia[edit]

Scythia (/ˈsɪθiə/; Ancient Greek: Σκυθική) was a region of Central Eurasia in classical antiquity, occupied by the Eastern Iranian Scythians,[5][6][7] encompassing parts of Eastern Europe east of the Vistula River and Central Asia, with the eastern edges of the region vaguely defined by the Greeks.[citation needed] The Ancient Greeks gave the name Scythia (or Great Scythia) to all the lands north-east of Europe and the northern coast of the Black Sea.[8] The Scythians—the Greeks' name for this initially nomadic people—inhabited Scythia from at least the 11th century BCE to the 2nd century CE.[9]

Sarmatia

The Sarmatians (Latin: Sarmatæ or Sauromatæ; Ancient Greek: Σαρμάται, Σαυρομάται) were a large confederation[10] of Iranian people during classical antiquity,[11][12] flourishing from about the 6th century BCE to the 4th century CE.[13] They spoke Scythian, an Indo-European language from the Eastern Iranian family. According to authors Arrowsmith, Fellowes and Graves Hansard in their book A Grammar of Ancient Geography published in 1832, Sarmatia had two parts, Sarmatia Europea [14] and Sarmatia Asiatica [15] covering a combined area of 503,000 sq mi or 1,302,764 km2. Sarmatians were basically Scythian veterans (Saka, Iazyges, Skolotoi, Parthians...) returning to the Pontic–Caspian steppe after the siege of Nineveh. Many noble families of Polish Szlachta claimed a direct descent from Sarmatians as a part of Sarmatism.

Xiongnu[edit]

The Xiongnu were a confederation of nomadic tribes from northern China and Inner Asia with a ruling class of unknown origin and other subjugated tribes. They lived on the Mongolian Plateau between the 3rd century BCE and the 460s CE, their territories including the modern-day northern China, Mongolia, southern Siberia. The Xiongnu was the first unified empire of nomadic peoples. Relations between early Central Plain dynasties and the Xiongnu were complicated and included military conflict, exchanges of tribute and trade, and marriage alliances. When Qin Shi Huang drove them away from the south of the Yellow River, he built the Great Wall to prevent the Xiongnu from returning.

Kushan Empire[edit]

The Kushan Empire was a syncretic empire, formed by the Yuezhi who originally hailed from the modern-day Chinese province of Gansu under the pressure of the Xiongnu, in the Bactrian territories in the early 1st century. It spread to encompass much of modern-day Afghanistan,[16] and then the northern parts of the Indian subcontinent at least as far as Saketa and Sarnath near Varanasi (Benares), where inscriptions have been found dating to the era of the Kushan emperor Kanishka the Great.[17]

Xianbei

Inner Mongolia, northern Xinjiang, Northeast China, Gansu, Mongolia, Buryatia, Zabaykalsky Krai, Irkutsk Oblast, Tuva, Altai Republic and eastern Kazakhstan from 156 to 234 CE. Like most ancient peoples known through Chinese historiography, the ethnic makeup of the Xianbei is unclear.[18] The Xianbei were a northern branch of the earlier Donghu and it is likely at least some were proto-Mongols. After it collapsed, the tribe immigrated into the Central Plain and founded the Northern Wei dynasty.[19]

Inner Mongolia, northern Xinjiang, Northeast China, Gansu, Mongolia, Buryatia, Zabaykalsky Krai, Irkutsk Oblast, Tuva, Altai Republic and eastern Kazakhstan from 156 to 234 CE. Like most ancient peoples known through Chinese historiography, the ethnic makeup of the Xianbei is unclear.[18] The Xianbei were a northern branch of the earlier Donghu and it is likely at least some were proto-Mongols. After it collapsed, the tribe immigrated into the Central Plain and founded the Northern Wei dynasty.[19]

Hephthalite Empire[edit]

The Hephthalites, Ephthalites, Ye-tai, White Huns, or, in Sanskrit, the Sveta Huna, were a confederation of nomadic and settled[20] people in Central Asia who expanded their domain westward in the 5th century.[21] At the height of its power in the first half of the 6th century, the Hephthalite Empire controlled territory in present-day Afghanistan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan, Pakistan, India and China.[22][23]

Hunnic Empire[edit]

The Huns were a confederation of Eurasian tribes from the Steppes of Central Asia. Appearing from beyond the Volga River some years after the middle of the 4th century, they conquered all of eastern Europe, ending up at the border of the Roman Empire in the south, and advancing far into modern day Germany in the north. Their appearance in Europe brought with it great ethnic and political upheaval and may have stimulated the Great Migration. The empire reached its largest size under Attila between 447 and 453.

Post-classical history[edit]

Mongolic people and Turkic expansion[edit]

Bulgars[edit]

The Bulgars (also Bulghars, Bulgari, Bolgars, Bolghars, Bolgari,[24] Proto-Bulgarians[25]) were Turkic semi-nomadic warrior tribes that flourished in the Pontic–Caspian steppe and the Volga region during the 7th century. Emerging as nomadic equestrians in the Volga-Ural region, according to some researchers their roots can be traced to Central Asia.[26] During their westward migration across the Eurasian steppe the Bulgars absorbed other ethnic groups and cultural influences, including Hunnic and Indo-European peoples.[27][28][29][30][31][32] Modern genetic research on Central Asian Turkic people and ethnic groups related to the Bulgars points to an affiliation with Western Eurasian populations.[32][33][34] The Bulgars spoke a Turkic language, i.e. Bulgar language of Oghuric branch.[35] They preserved the military titles, organization and customs of Eurasian steppes,[36] as well as pagan shamanism and belief in the sky deity Tangra.[37]

After Dengizich's death, the Huns seem to have been absorbed by other ethnic groups such as the Bulgars.[38] Kim, however, argues that the Huns continued under Ernak, becoming the Kutrigur and Utigur Hunno-Bulgars.[39] This conclusion is still subject to some controversy. Some scholars also argue that another group identified in ancient sources as Huns, the North Caucasian Huns, were genuine Huns.[40] The rulers of various post-Hunnic steppe peoples are known to have claimed descent from Attila in order to legitimize their right to the power, and various steppe peoples were also called "Huns" by Western and Byzantine sources from the fourth century onward.[41]

The first clear mention and evidence of the Bulgars was in 480, when they served as the allies of the Byzantine Emperor Zeno (474–491) against the Ostrogoths.[42] Anachronistic references about them can also be found in the 7th-century geography work Ashkharatsuyts by Anania Shirakatsi, where the Kup'i Bulgar, Duč'i Bulkar, Olxontor Błkar and immigrant Č'dar Bulkar tribes are mentioned as being in the North Caucasian-Kuban steppes.[43] An obscure reference to Ziezi ex quo Vulgares, with Ziezi being an offspring of Biblical Shem, is in the Chronography of 354.[43][44]

The Bulgars became semi-sedentary during the 7th century in the Pontic-Caspian steppe, establishing the polity of Old Great Bulgaria c. 635, which was absorbed by the Khazar Empire in 668 CE.

In c. 679, Khan Asparukh conquered Scythia Minor, opening access to Moesia, and established the First Bulgarian Empire, where the Bulgars became a political and military elite. They merged subsequently with established Byzantine populations,[45][46] as well as with previously settled Slavic tribes, and were eventually Slavicized, thus forming the ancestors of modern Bulgarians.[47]

Rouran

The Rouran (柔然), Juan Juan (蠕蠕), or Ruru (茹茹) were a confederation of Mongolic-speaking[48] nomadic tribes in northern China from the late 4th century until the late 6th century. They controlled an area corresponding to modern-day northern China, Mongolia, and southern Siberia.

Göktürks[]

The Göktürks or Kök-Türks were a Turkic people of inhabiting much of northern China and Inner Asia. Under the leadership of Bumin Khan and his sons they established the First Turkic Khaganate around 546, taking the place of the earlier Xiongnu as the main power in the region. They were the first Turkic tribe to use the name Türk as a political name. The empire was split into a western and an eastern part around 600, and both divisions were eventually conquered by the Tang dynasty. In 680, the Göktürks established the Second Turkic Khaganate which later declined after 734 following the establishment of the Uyghur Khaganate.

Kyrgyz[edit]

The Yenisei Kyrgyz Khaganate was a Turkic-led empire occupying the territories of modern-day northern China, Mongolia, and southern Siberia around the Yenisei River. The khaganate was founded in 693 by Bars Bek, and in 695, after a confrontation with the Second Turkic Khaganate, was recognised by Qapagan. In 710–711, as a result of the war with the Göktürks, the Kyrgyz Khaganate fell, and the descendants of Bars Bek remained vassals of the Second Turkic Khaganate until its fall in 744. After that, the Kyrgyz tribes became part of the ascendant Uyghur Khaganate. In 820, war broke out between the Kyrgyz and the Uyghur Khaganate, which continued with varying success for 20 years. In 840, the Uyghur Khaganate fell, and the Kyrgyz Khaganate was restored on its territory. It reached its peak of power at the end of the 9th century, but had little geopolitical influence thereafter. Eventually, the Kyrgyz Khaganate was finally dissolved in 1207 after becoming part of the Mongol Empire.

Uyghurs

The Uyghur Khaganate was an empire that existed in present-day northern China, Mongolia, southern Siberia, and surrounding areas for about a century between the mid 8th and 9th centuries. It was a tribal confederation under the Orkhon Uyghur nobility. It was established by Kutlug I Bilge Kagan in 744, taking advantage of the power vacuum in the region after the fall of the Gökturk Empire. It collapsed after a Kyrgyz invasion in 840.

Khitans[edit]

The Liao dynasty was ruled by the Yelü clan of the Khitan people in northern China. It was founded by Yelü Abaoji (Emperor Taizu of Liao) around the time of the collapse of the Tang dynasty and was the first state to control all of Manchuria.[49] After the Liao dynasty fell to the Jin dynasty in the 12th century, remnants of the Liao imperial clan led by Yelü Dashi (Emperor Dezong of Western Liao) fled west and established the Western Liao dynasty.

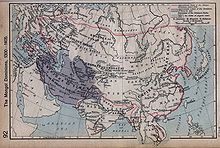

Mongol Empire[edit]

The Mongol Empire was the largest contiguous land empire in history at its peak, with an estimated population of over 100 million people. The Mongol Empire was founded by Genghis Khan in 1206, and at its height, it encompassed the majority of the territories from East Asia to Eastern Europe.

After unifying the Turco-Mongol tribes, the Empire expanded through conquests throughout continental Eurasia. During its existence, the Pax Mongolica facilitated cultural exchange and trade on the Silk Route between the East, West, and the Middle East in the period of the 13th and 14th centuries. It had significantly eased communication and commerce across Asia during its height.[50][51]

After the death of Möngke Khan in 1259, the empire split into four parts (Yuan dynasty, Ilkhanate, Chagatai Khanate and Golden Horde), each of which was ruled by its own monarch, although the emperors of the Yuan dynasty had nominal title of Khagan. After the disintegration of the western khanates and the fall of the Yuan dynasty in 1368, the empire finally broke up.

Timurid Empire[edit]

The Timurids, self-designated Gurkānī, were a Turko-Mongol dynasty, established by the warlord Timur in 1370 and lasting until 1506. At its zenith, the Timurid Empire included the whole of Central Asia, Iran and modern Afghanistan, as well as large parts of Mesopotamia and the Caucasus.

Modern history[edit]

Later Mongol-ruled khanates[edit]

Later Mongol-led khanates such as the Northern Yuan dynasty and the Dzungar Khanate were also nomadic empires. After the fall of the Yuan dynasty in 1368, the Ming dynasty rebuilt the Great Wall, which had been begun many hundreds of years earlier to keep the northern nomads out of the Central Plain. During the subsequent centuries, the Northern Yuan dynasty tended to continue their nomadic way of life.[52] On the other hand, the Dzungars were a confederation of several Oirat tribes who formed and maintained the last horse archer empire from the early 17th century to the middle 18th century. They emerged in the early 17th century to fight the Altan Khan of the Khalkha, the Jasaghtu Khan and their Manchu patrons for dominion and control over the Mongol tribes. In 1756, this last nomadic power was dissolved due to the Oirat princes' succession struggle and costly war with the Qing dynasty.

Medieval Turkic khanates[edit]

The Kazakh Khanate (Kazakh: Қазақ Хандығы, Qazaq Handyǵy, قازاق حاندىعى) was a successor of the Golden Horde existing from the 15th to 19th century, located roughly on the territory of the present-day Republic of Kazakhstan. At its height, the khanate ruled from eastern Cumania (modern-day West Kazakhstan) to most of Uzbekistan, Karakalpakstan and the Syr Darya river with military confrontation as far as Astrakhan and Khorasan Province, which are now in Russia and Iran, respectively. The Khanate also engaged in slavery and raids in its neighboring countries of Russia and Central Asia, and was later weakened by a series of Oirat and Dzungar invasions. These resulted in a decline and further disintegration into three Jüz-es, which gradually lost their sovereignty and were incorporated to the expanding Russian Empire. Its establishment marked the beginning of Kazakh statehood[53] whose 550th anniversary was celebrated in 2015.[54]

Popular misconceptions[edit

The Qing dynasty is mistakenly confused as a nomadic empire by people who wrongly think that the Manchus were a nomadic people,[55] when in fact they were not nomads,[56][57] but instead were a sedentary agricultural people who lived in fixed villages, farmed crops, and practiced hunting and mounted archery.

The Sushen used flint-headed wooden arrows, farmed, hunted, and fished and lived in caves and trees.[58] The cognates Sushen or Jichen (稷真) again appear in the Shan Hai Jing and Book of Wei during the dynastic era referring to Tungusic Mohe tribes of the far northeast.[59] The Mohe enjoyed eating pork, practiced pig farming extensively, and were mainly sedentary,[60] and also used both pig and dog skins for coats. They were predominantly farmers and grew soybean, wheat, millet, and rice, in addition to engaging in hunting.[61]

The Jurchens were sedentary,[62] settled farmers with advanced agriculture. They farmed grain and millet as their cereal crops, grew flax, and raised oxen, pigs, sheep, and horses.[63] Their farming way of life was very different from the pastoral nomadism of the Mongols and the Khitan on the steppes.[64][65] "At the most", the Jurchen could only be described as "semi-nomadic" while the majority of them were sedentary.[66]

The Manchu way of life (economy) was described as agricultural, with farming crops and raising animals on farms.[67] Manchus practiced slash-and-burn agriculture in the areas north of Shenyang.[68] The Haixi Jurchens were "semi-agricultural, the Jianzhou Jurchens and Maolian (毛怜) Jurchens were sedentary, and hunting and fishing was the way of life of the "Wild Jurchens".[69] Han Chinese society resembled that of the sedentary Jianzhou and Maolian, who were farmers.[70] Hunting, archery on horseback, horsemanship, livestock raising, and sedentary agriculture were all practiced by the Jianzhou Jurchens as part of their culture.[71] In spite of the fact that the Manchus practiced archery on horseback and equestrianism, the Manchu's immediate progenitors practiced sedentary agriculture.[72] Although the Manchus also partook in hunting, they were sedentary.[73] Their primary mode of production was farming, and they lived in villages, forts, and towns surrounded by walls. Farming was practiced by their Jurchen Jin predecessors.[74][75]

"The (people of) Chien-chou and Mao-lin [YLSL always reads Mao-lien] are the descendants of the family Ta of Po-hai. They love to be sedentary and sow, and they are skilled in spinning and weaving. As for food, clothing and utensils, they are the same as (those used by) the Chinese. (Those living) south of the Ch'ang-pai mountain are apt to be soothed and governed."

[76] Translation from Sino-J̌ürčed relations during the Yung-Lo period, 1403–1424 by Henry Serruys[77]

For political reasons, the Jurchen leader Nurhaci chose variously to emphasize either differences or similarities in lifestyles with other peoples like the Mongols.[78] Nurhaci said to the Mongols, "The languages of the Chinese and Koreans are different, but their clothing and way of life is the same. It is the same with us Manchus (Jušen) and Mongols. Our languages are different, but our clothing and way of life is the same." Later, Nurhaci indicated that the bond with the Mongols was not based in any real shared culture. It was for pragmatic reasons of "mutual opportunism" since Nurhaci said to the Mongols, "You Mongols raise livestock, eat meat and wear pelts. My people till the fields and live on grain. We two are not one country and we have different languages."[79]

Only the Mongols and the northern "wild" Jurchen were semi-nomadic, unlike the mainstream Jiahnzhou Jurchens descended from the Jin dynasty who were farmers that foraged, hunted, herded and harvested crops in the Liao and Yalu river basins. They gathered ginseng root, pine nuts, hunted for came pels in the uplands and forests, raised horses in their stables, and farmed millet and wheat in their fallow fields. They engaged in dances, wrestling and drinking strong liquor as noted during midwinter by the Korean Sin Chung-il when it was very cold. These Jurchens who lived in the north-east's harsh cold climate sometimes half sunk their houses in the ground which they constructed of brick or timber and surrounded their fortified villages with stone foundations on which they built wattle and mud walls to defend against attack. Village clusters were ruled by beile, hereditary leaders. They fought each other and dispensed weapons, wives, slaves, and lands to their followers in them.

The Jurchens who founded the Qing lived and their ancestors lived in such a way before the Jin. Alongside Mongols and Jurchen clans there were migrants from Liaodong provinces of the Ming dynasty and Joseon living among those Jurchens in a cosmopolitan manner. Nurhaci who was hosting Sin Chung-il was uniting all of them into his own army, having them adopt the Jurchen hairstyle of a long queue and a shaved fore=crown and wearing leather tunics. His armies had black, blue, red, white, and yellow flags. They became the Eight Banners, which was initially capped to 4 and then grew to 8 with three different types of ethnic banners as Han, Mongol and Jurchen were recruited into Nurhaci's forces. Jurchens like Nurhaci spoke both their native Tungusic language and Chinese and adopted the Mongol script for their own language unlike the Jin Jurchen's script, which was derived from Khitan. They adopted Confucian values and practiced their shamanist traditions.[80]

The Qing stationed "New Manchu" Warka foragers in Ningguta and attempted to turn them into normal agricultural farmers like normal Old Manchus, but the Warka just reverted to hunter gathering and requested money to buy cattle for beef broth. The Qing wanted the Warka to become soldier-farmers and imposed that on them, but the Warka simply left their garrison at Ningguta and went back to the Sungari River to their homes to herd, fish, and hunt. The Qing accused them of desertion.[81]

Similarly, the Indo-European dominions, like the Cimmerian, Scythian, Sarmatian or Kushan ones, were not strictly nomadic or strictly empires. They were organized in small Kšatrapies/Voivodeships that sometimes united into a bigger Mandala to repel surrounding despotic empires trying to annex their homelands. Only the pastoral part of the population and military troops migrated frequently, but most of the population lived in organized agricultural and industrial small scale townships, which are called in Europe gords.

Examples are the oases of Sogdia and Sparia along the Silk Road (Śaka, Tokarians/Tokharians etc.) and around the Tarim Basin (Tarim mummies, Kingdom of Khotan) or the rural areas of Europe (Sarmatia, Pannonia, Vysperia, Spyrgowa/Spirgovia, Boioaria/Boghoaria...) and Indian subcontinent (Kaśperia, Pandžab etc.).

Since the 2nd century BCE), the growing number of Turkic nomads and invaders among them, who adopted their horse-riding, metallurgy, technologies, clothing, and customs caused them to be also often confused with the latter, which mostly occurred in the case of the Scythians (Śaka, Sarmatians, Skolotoi, Iazyges, etc.).

In India, the Śaka, although known earlier as Śakya or Kambojas, formed now the Kushan Empire but were confused with the Xionites invading them and were called Mleccha.

The Turkic invaders exploited the subdued sedentary Indo-Europeans in agriculture, industry, and warfare (Mamluk, Janissaries). In some rare cases, the enslaved Indo-Europeans may rise to power like Aleksandra (Iškandara) Lisowska or Roxelana.

Leaders like Genghis Khan managed to unite the tribes and followed a successful and maybe a necessary strategy. They oriented their warriors’ energy to the outer targets. It was necessary because nomad resources were simply not enough for all.

When armies get crowded, it was better to choose bigger and lucrative targets to distribute the wealth in equal terms. Otherwise, nomads fought with each other in limited space and for poor resources. Therefore, the usual foreign target was relatively rich China for centuries.

Similar story was also valid for Germanic people (they eventually oriented their energy to Roman Empire) or Slavic people (migration of tribes). The main reason for expansion was a very simple one. Space and resources were not enough for warrior type nations… It was not all about pillage and getting booty… Actually, nomads were culture carriers between west and east… For ex: Huns pushed Germans westward. Germans only wanted to be part of Roman Empire and become farmers… However, Romans foolishly preferred to destroy them, instead they destroyed Roman army at Battle of Adrianople (378 AD).

The known world of trade was Mediterranean and Silk Road. Mongols naturally opted to control the trade routes. they created Pax Mongol successfully.

in Hunnic times… ‘’ As the Huns moved along the Black Sea, they attacked those in their path. These people—Vandals, Visigoths, Goths and other groups—fled toward Rome. These migrations destabilized the Roman Empire and helped the Huns gain a murderous reputation.

Their most notorious leader, Attila the Hun, solidified that perception. Between 440 and 453 A.D., he led Hunnic hordes throughout much of Europe, including Gaul (modern-day France). Along the way he pillaged with abandon, gaining a reputation in historical accounts as a “Scourge of God” whose people perpetrated unspeakable acts of terror whenever they entered new territory.

. As the nomadic Huns moved westward across Asia wreaking havoc, the Visigoths, numbering over 200,000, moved from modern-day Ukraine to the frontier of the Roman Empire and, in 376 CE, crossed the Danube River and established themselves in Thrace. As the Huns continued their way westward into Europe the Gothic and Roman leadership made an alliance, and the tribes were finally given permission to permanently settle.

Xianbei/Người Tiên Ti

| Xianbei | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 鮮卑 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 鲜卑 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Xianbei (/ʃjɛnˈbeɪ/; Chinese: 鮮卑; pinyin: Xiānbēi) were most likely a Proto-Mongolic[1] ancient nomadic people that once resided in the eastern Eurasian steppes in what is today Mongolia, Inner Mongolia, and Northeastern China. There are also other strong suggestions that they were a multi-ethnic confederation with Mongolic and Turkic influences.[2][3] They originated from the Donghu people who splintered into the Wuhuan and Xianbei when they were defeated by the Xiongnu at the end of the third century BC. The Xianbei were largely subordinate to larger nomadic powers and the Han dynasty until they gained prominence in 87 AD by killing the Xiongnu chanyu Youliu. However unlike the Xiongnu, the Xianbei political structure lacked the organization to pose a concerted challenge to the Chinese for most of their time as a nomadic people.

After suffering several defeats by the end of the Three Kingdoms period, the Xianbei migrated south and settled in close proximity to Han society and submitted as vassals, being granted the titles of dukes. As the Xianbei Murong, Tuoba, and Duan tribes were one of the Five Barbarians who were vassals of the Western Jin and Eastern Jin dynasties, they took part in the Uprising of the Five Barbarians as allies of the Eastern Jin against the other four barbarians, the Xiongnu, Jie, Di and Qiang.[4][5]

The Xianbei were at one point all defeated and conquered by the Di-led Former Qin dynasty before it fell apart not long after its defeat in the Battle of Fei River by the Eastern Jin. The Xianbei later founded their own dynasties and reunited northern China under the Northern Wei dynasty. These states opposed and promoted sinicization at one point or another but trended towards the latter and had merged with the general Chinese population by the Tang dynasty.[6][7][8][9][10] The Northern Wei also arranged for ethnic Han elites to marry daughters of the Tuoba imperial clan in the 480s.[11] More than fifty percent of Tuoba Xianbei princesses of the Northern Wei were married to southern Han men from the imperial families and aristocrats from southern China of the Southern dynasties who defected and moved north to join the Northern Wei.[12]

Etymology[edit]

Paul Pelliot tentatively reconstructs the Later Han Chinese pronunciation of 鮮卑 as */serbi/, from *Särpi, after noting that Chinese scribes used 鮮 to transcribe Middle Persian sēr (lion) and 卑 to transcribe foreign syllable /pi/; for instance, Sanskrit गोपी gopī "milkmaid, cowherdess" became Middle Chinese 瞿卑 (ɡɨo-piᴇ) (> Mand. qúbēi).[13]

On the one hand, *Särpi may be linked to Mongolic root *ser ~*sir which means "crest, bristle, sticking out, projecting, etc." (cf. Khalkha сэрвэн serven), possibly referring to the Xianbei's horses (semantically analogous with the Turkic ethnonym Yabaqu < Yapağu 'matted hair or wool', later 'a matted-haired animal, i.e. a colt')[14] On the other hand, Book of Later Han and Book of Wei stated that: before becoming an ethnonym, Xianbei had been a toponym, referring to the Great Xianbei mountains (大鮮卑山), which is now identified as the Greater Khingan range (simplified Chinese: 大兴安岭; traditional Chinese: 大興安嶺; pinyin: Dà Xīng'ān Lǐng).[15][16][17]

Shimunek (2018) reconstructs *serbi for Xiānbēi and *širwi for 室韋 Shìwéi < MC *ɕiɪt̚-ɦʉi.[18] This same root might be the origin of ethnonym Sibe.[citation needed]

History[edit]

Origin[edit]

Warring States period's Chinese literature contains early mentions of Xianbei, as in the poem "The Great Summons" (Chinese: 大招; pinyin: Dà zhāo) in the anthology Verses of Chu[19] and the chapter "Discourses of Jin 8" in Discourses of the States.[20][21]

When the Donghu "Eastern Barbarians" were defeated by Modu Chanyu around 208 BC, the Donghu splintered into the Xianbei and Wuhuan.[22] According to the Book of the Later Han, "the language and culture of the Xianbei are the same as the Wuhuan".[23]

The first significant contact the Xianbei had with the Han dynasty was in 41 and 45, when they joined the Wuhuan and Xiongnu in raiding Han territory.[24]

In 49, the governor Ji Tong convinced the Xianbei chieftain Pianhe to turn on the Xiongnu with rewards for each Xiongnu head they collected.[24] In 54, Yuchouben and Mantou of the Xianbei paid tribute to Emperor Guangwu of Han.[25]

In 58, the Xianbei chieftain Pianhe attacked and killed Xinzhiben, a Wuhuan leader causing trouble in Yuyang Commandery.[26]

In 85, the Xianbei secured an alliance with the Dingling and Southern Xiongnu.[24]

In 87, the Xianbei attacked the Xiongnu chanyu Youliu and killed him. They flayed him and his followers and took the skins back as trophies.[27]

Xianbei Confederation[edit]

After the downfall of the Xiongnu, the Xianbei established their confederation in Mongolia starting from AD 93.

In 109, the Wuhuan and Xianbei attacked Wuyuan Commandery and defeated local Han forces.[28] The Southern Xiongnu chanyu Wanshishizhudi rebelled against the Han and attacked the Emissary Geng Chong but failed to oust him. Han forces under Geng Kui retaliated and defeated a force of 3,000 Xiongnu but could not take the Southern Xiongnu capital due to disease among the horses of their Xianbei allies.[28]

The Xianbei under Qizhijian raided Han territory four times from 121 to 138. .[29] In 145, the Xianbei raided Dai Commandery.[30]

Around 155, the northern Xiongnu were "crushed and subjugated" by the Xianbei. Their chief, known by the Chinese as Tanshihuai, then advanced upon and defeated the Wusun of the Ili region by 166. Under Tanshihuai, the Xianbei extended their territory from the Ussuri to the Caspian Sea. He divided the Xianbei empire into three sections, each ruled by twenty clans. Tanshihuai then formed an alliance with the southern Xiongnu to attack Shaanxi and Gansu. Han dynasty successfully repulsed their attacks in 158, 177. The Xianbei might have also attacked Wa (Japan) with some success.[31][32][33]

In 177 AD, Xia Yu, Tian Yan and the Tute Chanyu led a force of 30,000 against the Xianbei. They were defeated and returned with only a quarter of their original forces.[34] A memorial made that year records that the Xianbei had taken all the lands previously held by the Xiongnu and their warriors numbered 100,000. Han deserters who sought refuge in their lands served as their advisers and refined metals as well as wrought iron came into their possession. Their weapons were sharper and their horses faster than those of the Xiongnu. Another memorial submitted in 185 states that the Xianbei were making raids on Han settlements nearly every year.[35]

Three Kingdoms[edit]

The loose Xianbei confederacy lacked the organization of the Xiongnu but was highly aggressive until the death of their khan Tanshihuai in 182.[37] Tanshihuai's son Helian lacked his father's abilities and was killed in a raid on Beidi in 186.[38] Helian's brother Kuitou succeeded him, but when Helian's son Qianman came of age, he challenged his uncle to succession, destroying the last vestiges of unity among the Xianbei. By 190, the Xianbei had split into three groups with Kuitou ruling in Inner Mongolia, Kebineng in northern Shanxi, and Suli and Mijia in northern Liaodong. In 205, Kuitou's brothers Budugen and Fuluohan succeeded him. After Cao Cao defeated the Wuhuan at the Battle of White Wolf Mountain in 207, Budugen and Fuluohan paid tribute to him. In 218, Fuluohan met with the Wuhuan chieftain Nengchendi to form an alliance, but Nengchendi double crossed him and called in another Xianbei khan, Kebineng, who killed Fuluohan.[39] Budugen went to the court of Cao Wei in 224 to ask for assistance against Kebineng, but he eventually betrayed them and allied with Kebineng in 233. Kebineng killed Budugen soon afterwards.[40]

Kebineng was from a minor Xianbei tribe. He rose to power west of Dai Commandery by taking in a number of Chinese refugees, who helped him drill his soldiers and make weapons. After the defeat of the Wuhuan in 207, he also sent tribute to Cao Cao, and even provided assistance against the rebel Tian Yin. In 218 he allied himself to the Wuhuan rebel Nengchendi but they were heavily defeated and forced back across the frontier by Cao Zhang. In 220, he acknowledged Cao Pi as emperor of Cao Wei. Eventually, he turned on the Wei for frustrating his advances on another Xianbei khan, Sui. Kebineng conducted raids on Cao Wei before he was killed in 235, after which his confederacy disintegrated.[41]

Many of the Xianbei tribes migrated south and settled on the borders of the Wei-Jin dynasties. In 258 Tuoba Liwei's people settled in Yanmen Commandery.[4] The Yuwen tribe settled between the Luan River and Liucheng. The Murong and Duan tribes became vassals of the Sima clan. An offshoot of the Murong tribe moved west into northern Qinghai and mixed with the native Qiang people, becoming Tuyuhun.[24]

In 279, the Xianbei made one last attack on Liang Province but they were defeated by Ma Long.[31]

Sixteen Kingdoms, Nirun and Northern Wei[edit]

The third century saw both the fragmentation of the Xianbei in 235 and the branching out of the various Xianbei tribes.

Around 308 or 330 AD, the Rouran tribe was founded by Mugulü, but formed by his son, Cheluhui.[42] The Xianbei tribes Tuoba, Murong and Duan submitted to the Western Jin dynasty as vassals, the Tuoba were made Dukes of Dai (Sixteen Kingdoms), the Murong were made Dukes of Liaodong, and the Duan were made Dukes of Liaoxi. The three Xianbei tribes fought on the Western Jin side against the other four barbarians in the Uprising of the Five Barbarians after a Xiongnu and Jie led slave revolt toppled Western Jin rule in northern China. Mass number of Chinese officers, soldiers and civilians fled south to join the Eastern Jin or north to join the Xianbei duchies which remained in direct communication with the Eastern Jin in southern China, receiving orders.

The Xianbei later establish six significant empires of their own such as the Former Yan (281–370), Western Yan (384–394), Later Yan (384–407), Southern Yan (398–410), Western Qin (385–430) and Southern Liang (397–414). The Xianbei were all conquered by the Di Former Qin empire in northern China before its defeat at the Battle of Fei River and subsequent collapse.

Most of them were unified by the Tuoba Xianbei, who established the Northern Wei (386–535), which was the first of the Northern Dynasties (386–581) founded by the Xianbei.[43][44][45]

Sinicization and assimilation[edit]

Emperor Xiaowen of Northern Wei established a policy of systematic sinicization that was continued by his successors. Xianbei traditions were largely abandoned. The royal family took the sinicization a step further by changing their family name to Yuan. Marriages to Han elite families were encouraged.

The Northern Wei started to arrange for Han Chinese elites to marry daughters of the Xianbei Tuoba royal family in the 480s.[11] More than fifty percent of Tuoba Xianbei princesses of the Northern Wei were married to southern Han Chinese men from the imperial families and aristocrats from southern China of the Southern dynasties who defected and moved north to join the Northern Wei.[46] Some Han Chinese exiled royalty fled from southern China and defected to the Xianbei. Several daughters of the Xianbei Emperor Xiaowen of Northern Wei were married to Han Chinese elites, the Liu Song royal Liu Hui (刘辉), married Princess Lanling (蘭陵公主) of the Northern Wei,[47][48][49][50][51] Princess Huayang (華陽公主) to Sima Fei (司馬朏), a descendant of Jin dynasty (266–420) royalty, Princess Jinan (濟南公主) to Lu Daoqian (盧道虔), Princess Nanyang (南阳长公主) to Xiao Baoyin (萧宝夤), a member of Southern Qi royalty.[52] Emperor Xiaozhuang of Northern Wei's sister the Shouyang Princess was wedded to The Liang dynasty ruler Emperor Wu of Liang's son Xiao Zong 蕭綜.[53]

When the Eastern Jin dynasty ended, Northern Wei received the Han Chinese Jin prince Sima Chuzhi (司馬楚之) as a refugee. A Northern Wei Princess married Sima Chuzhi, giving birth to Sima Jinlong. Northern Liang Xiongnu King Juqu Mujian's daughter married Sima Jinlong.[54]

In 534, the Northern Wei split into an Eastern Wei (534–550) and a Western Wei (535–556) after an uprising in the steppes of North China inhabited by Xianbei and other nomadic peoples.[55] The former evolved into the Northern Qi (550-577), and the latter into the Northern Zhou (557-581), while the Southern Dynasties were pushed to the south of the Yangtze River. In 581, the Prime Minister of Northern Zhou, Yang Jian, founded the Sui dynasty (581–618). His son, the future Emperor Yang of Sui, absorbed the Chen dynasty (557–589), the last kingdom of the Southern Dynasties, thereby unifying much of China. After the Sui came to an end amidst peasant rebellions and renegade troops, his cousin, Li Yuan, founded the Tang dynasty (618–907). Sui and Tang dynasties were founded by Han generals who also served the Northern Wei dynasty.[56][57] Through these political establishments, the Xianbei who entered China were largely merged with the Chinese, examples such as the wife of Emperor Gaozu of Tang, Duchess Dou and Emperor Taizong of Tang's wife, Empress Zhangsun, both have Xianbei ancestries,[58] while those who remained behind in the northern grassland emerged as later powers to rule over China as Mongol Yuan dynasty and Manchu Qing dynasty.

In the West, the Xianbei kingdom of Tuyuhun remained independent until it was defeated by the Tibetan Empire in 670. After the fall of the kingdom, the Xianbei people underwent a diaspora over a vast territory that stretched from the northwest into central and eastern parts of China. Murong Nuohebo led the Tuyuhun people eastward into central China, where they settled in modern Yinchuan, Ningxia.

Art[edit]

Art of the Xianbei portrayed their nomadic lifestyle and consisted primarily of metalwork and figurines. The style and subjects of Xianbei art were influenced by a variety of influences, and ultimately, the Xianbei were known for emphasizing unique nomadic motifs in artistic advancements such as leaf headdresses, crouching and geometricized animals depictions, animal pendant necklaces, and metal openwork.[59]

Leaf headdresses[edit]

The leaf headdresses were very characteristic of Xianbei culture, and they are found especially in Murong Xianbei tombs. Their corresponding ornamental style also links the Xianbei to Bactria. These gold hat ornaments represented trees and antlers and, in Chinese, they are referred to as buyao ("step sway") since the thin metal leaves move when the wearer moves. Sun Guoping first uncovered this type of artifact, and defined three main styles: "Blossoming Tree" (huashu), which is mounted on the front of a cap near the forehead and has one or more branches with hanging leaves that are circle or droplet shaped, "Blossoming Top" (dinghua), which is worn on top of the head and resembles a tree or animal with many leaf pendants, and the rare "Blossoming Vine" (huaman), which consists of "gold strips interwoven with wires with leaves."[60] Leaf headdresses were made with hammered gold and decorated by punching out designs and hanging the leaf pendants with wire. The exact origin, use, and wear of these headdresses is still being investigated and determined. However, headdresses similar to those later also existed and were worn by women in the courts.[59][60]

Animal iconography[edit]

Another key form of Xianbei art is animal iconography, which was implemented primarily in metalwork. The Xianbei stylistically portrayed crouching animals in geometricized, abstracted, repeated forms, and distinguished their culture and art by depicting animal predation and same-animal combat. Typically, sheep, deer, and horses were illustrated. The artifacts, usually plaques or pendants, were made from metal, and the backgrounds were decorated with openwork or mountainous landscapes, which harks back to the Xianbei nomadic lifestyle. With repeated animal imagery, an openwork background, and a rectangular frame, the included image of the three deer plaque is a paradigm of the Xianbei art style. Concave plaque backings imply that plaques were made using lost-wax casting, or raised designs were impressed on the back of hammered metal sheets.[61][62]

Horses[edit]

The nomadic traditions of the Xianbei inspired them to portray horses in their artwork. The horse played a large role in the existence of the Xianbei as a nomadic people, and in one tomb, a horse skull lay atop Xianbei bells, buckles, ornaments, a saddle, and one gilded bronze stirrup.[63] The Xianbei not only created art for their horses, but they also made art to depict horses. Another recurring motif was the winged horse. It has been suggested by archaeologist Su Bai that this symbol was a "heavenly beast in the shape of a horse" because of its prominence in Xianbei mythology.[61] This symbol is thought to have guided an early Xianbei southern migration, and is a recurring image in many Xianbei art forms.

Figurines[edit]

Xianbei figurines help to portray the people of the society by representing pastimes, depicting specialized clothing, and implying various beliefs. Most figurines have been recovered from Xianbei tombs, so they are primarily military and musical figures meant to serve the deceased in afterlife processions and guard the tomb. Furthermore, the figurine clothing specifies the according social statuses: higher-ranking Xianbei wore long-sleeved robes with a straight neck shirt underneath, while lower-ranking Xianbei wore trousers and belted tunics.[64]

Buddhist influences[edit]

Xianbei Buddhist influences were derived from interactions with Han culture. The Han bureaucrats initially helped the Xianbei run their state, but eventually the Xianbei became Sinophiles and promoted Buddhism. The beginning of this conversion is evidenced by the Buddha imagery that emerges in Xianbei art. For instance, the included Buddha imprinted leaf headdress perfectly represents the Xianbei conversion and Buddhist synthesis since it combines both the traditional nomadic Xianbei leaf headdress with the new imagery of Buddha. This Xianbei religious conversion continued to develop in the Northern Wei dynasty, and ultimately led to the creation of the Yungang Grottoes.[59]

Language[edit]

The Xianbei are thought to have spoken Mongolic or para-Mongolic languages, with early and substantial Turkic influences; as Claus Schönig asserts:

The Xianbei derived from the context of the Donghu, who are likely to have contained the linguistic ancestors of the Mongols. Later branches and descendants of the Xianbei include the Tabghach and Khitan, who seem to have been linguistically Para-Mongolic. [...] Opinions differ widely as to what the linguistic impact of the Xianbei period was. Some scholars (like Clauson) have preferred to regard the Xianbei and Tabghach (Tuoba) as Turks, with the implication that the entire layer of early Turkic borrowings in Mongolic would have been received from the Xianbei, rather than from the Xiongnu. However, since the Mongolic (or Para-Mongolic) identity of the Xianbei is increasingly obvious in the light of recent progress in Khitan studies, it is more reasonable to assume (with Doerfer) that the flow of linguistic influence from Turkic into Mongolic was at least partly reversed during the Xianbei period, yielding the first identifiable layer of Mongolic (or Para-Mongolic) loanwords in Turkic. [65]

It is also possible that the Xianbei spoke more than one language.[66] [67][68]

Anthropology[edit]

According to Sinologist Penglin Wang, some Xianbei had mixed west Eurasian-featured traits such as blue eyes, blonde hair and white skin due to absorbing some Indo-European elements. The Xianbei were described as white on several occasions. The Book of Jin states that in the state of Cao Wei, Xianbei immigrants were known as the white tribe. The ruling Murong clan of Former Yan were referred to by their Former Qin adversaries as white slaves. According to Fan Wenlang et al. the Murong people were considered "white" by the Chinese due to the complexion of their skin color. In the Jin dynasty, Xianbei Murong women were sold off to many Han Chinese bureaucrat and aristocrats and they were also given to their servants and concubines. The mother of Emperor Ming of Jin, Lady Xun, was a lowly concubine possibly of Xianbei stock. During a confrontation between Emperor Ming and a rebel force in 324, his enemies were confused by his appearance, and thought he was a Xianbei due to his yellow beard.[69] Emperor Ming's yellowish hair could have been inherited from his mother, who was either Xianbei or Jie. During the Tang dynasty, the poet Zhang Ji described the Xianbei entering Luoyang as "yellow-headed". During the Song dynasty, the poet and painter Su Shi was inspired by a painting of a Xianbei riding a horse and wrote a poem describing an elderly Xianbei with reddish hair and blue eyes.[70]

There was undoubtedly some range of variation within their population. Yellow hair in Chinese sources could have meant brown rather than blonde and described other people such as the Jie rather than the Xianbei. Historian Edward H. Schafer believes many of the Xianbei were blondes, but others such as Charles Holcombe think it is "likely that the bulk of the Xianbei were not visibly very different in appearance from the general population of northeastern Asia."[66] Chinese anthropologist Zhu Hong and Zhang Quan-chao studied Xianbei crania from several sites of Inner Mongolia and noticed that anthropological features of studied Xianbei crania show that the racial type is closely related to the modern East-Asians, and some physical characteristics of those skulls are closer to modern Mongols, Manchu and Han Chinese.[71]

Genetics[edit]

A genetic study published in The FEBS Journal in October 2006 examined the mtDNA of Twenty one Tuoba Xianbei buried at the Qilang Mountain Cemetery in Inner Mongolia, China. The Twenty one samples of mtDNA extracted belonged to haplogroups O (9 samples), D (7 samples), C (5 samples), B (2 samples) and A.[72] These haplogroups are characteristic of Northeast Asians.[73] Among modern populations they were found to be most closely related to the Oroqen people.[74]

A genetic study published in the Russian Journal of Genetics in April 2014 examined the mtDNA of seventeen Tuoba Xianbei buried at the Shangdu Dongdajing cemetery in Inner Mongolia, China. The seventeen samples of mtDNA extracted belonged to haplogroups D4 (four samples), D5 (three samples), C (five samples), A (three samples), G and B.[75]

A genetic study published in the American Journal of Physical Anthropology in November 2007 examined of 17 individuals buried at a Murong Xianbei cemetery in Lamadong, Liaoning, China ca. 300 AD.[76] They were determined to be carriers of the maternal haplogroups J1b1, D (three samples), F1a (three samples), M, B, B5b, C (three samples) and G2a.[77] These haplogroups are common among East Asians and some Siberians. The maternal haplogroups of the Murong Xianbei were noticeably different from those of the Huns and Tuoba Xianbei.[76]

A genetic study published in the American Journal of Physical Anthropology in August 2018 noted that the paternal haplogroup C2b1a1b has been detected among the Xianbei and the Rouran, and was probably an important lineage among the Donghu people.[78]

Notable people[edit]

Pre-dynastic[edit]

- Tanshihuai (檀石槐, 130–182), Xianbei leader who led the Xianbei State until his death in 182

- Kebineng (軻比能, died 235), a Xianbei chieftain who lived during the late Eastern Han dynasty and Three Kingdoms period

- Tufa Shujineng (禿髮樹機能, died 279), a Xianbei chieftain who lived during the Three Kingdoms period

Sixteen Kingdoms[edit]

Yan[edit]

- Murong Huang (慕容皝, 297–348), founder of the state Former Yan

- Murong Jun (慕容儁, 319–360), was the second ruler of the state Former Yan

- Murong Chui (慕容垂, 326–396), was a general of the state Former Yan who later became the founding emperor of Later Yan

- Murong Ke (慕容恪, died 367), a famed general and statesman of the state Former Yan

- Murong De (慕容德, 336–405), founder of the state Southern Yan

- Murong Chao (慕容超, 385–410), was the last emperor of the Murong Xianbei state Southern Yan

Dai[edit]

- Tuoba Yilu (拓跋猗盧, died 316), son of Tuoba Shamohan, who was head of the Tuoba clan, Duke of Dai, and later, Prince of Dai, being the founder of this Xianbei kingdom

Northern dynasties[edit]

- Tuoba Gui (拓跋珪, 371–409), founding emperor of the Northern Wei

- Tuoba Tao (拓拔燾, 408–452), was the third emperor of the Northern Wei

- Tufa Poqiang (禿髮破羌, 407–479), a paramount general of the Northern Wei

- Yuwen Tai (宇文泰, 507–556), a paramount general of the state Western Wei, a branch successor state of Northern Wei

- Dugu Xin (独孤信, 503–557), a paramount general of the state Western Wei

- Yuchi Jiong (尉遲迥, died 580), a paramount general of the states Western Wei and Northern Zhou

- Lou Zhaojun (婁昭君, 501–562), an empress dowager of the state Northern Qi

- Lu Lingxuan (陸令萱, died 577), a lady in waiting in the palace of the state Northern Qi

- Yuwen Hu (宇文護, 513–572), a regent of the state Northern Zhou

- Mu Tipo (穆提婆, 527–577), a paramount official of the state Northern Qi

- Mu Yeli (穆邪利, 557–577), an empress of the state Northern Qi

- Gao Anagong (高阿那肱, died 580), a paramount official and general of the state Northern Qi

- Queen Dugu (獨孤王后, 536–558), a queen of the state Northern Zhou

- Yuwen Yong (宇文邕, 543–578), emperor of the state Northern Zhou

"Nirun" and Rouran[edit]

Tribe[edit]

- Yujiulü Mugulü (郁久閭木骨閭, ?–?), was a Xianbei slave and the ancestor the Yujiulü clan, from whom sprang the founders of the Rouran Khaganate[42]

- Yujiulü Cheluhui (郁久閭車鹿會, ?–?), was ruler and tribal chief of the Rourans, succeeded Mùgǔlǘ (Mugulü) and was the son of the same[42]

Khaganate[edit]

- Yujiulü Shelun (郁久闾社仑, 391–410) was khagan of the Rouran from 402 to 410

- Yujiulü Datan (郁久閭大檀, died 429) khagan of the Rouran from 414 to July, 429

- Yujiulu Anagui (郁久閭阿那瓌, died 552) was ruler of the Rouran (520–552)

- Yujiulü Anluochen (郁久閭菴羅辰, died 554) was the last khagan of the Rouran (553–554) in the east. He was the son of Anagui

- Yujiulü Dengshuzi (郁久閭鄧叔子, died 555) was the last western khagan of the Rouran. He was a cousin of Anagui

Sui Dynasty[edit]

- Dugu Qieluo (獨孤伽羅, 544–602), formally Empress Wenxian (文獻皇后), was an empress of the Sui dynasty

- Yuchi Yichen (尉遲義臣, died 617), a prominent general of Sui Dynasty

- Yuwen Shu (宇文述, died 616), a paramount general of Sui dynasty

- Yuwen Huaji (宇文化及, 569–619), a paramount general of Sui dynasty

- Yuwen Zhiji (宇文智及, 572–619), a general of Sui dynasty

Tang Dynasty[edit]

- Empress Zhangsun (長孫皇后, 601–636), was an empress of Tang dynasty. She was the wife of Emperor Taizong

- Zhangsun Wuji (長孫無忌, died 659), a paramount official who served both as general and chancellor in the early Tang dynasty

- Yuchi Jingde (尉遲敬德, 585–658), a famous general who lived in the early Tang dynasty, Yuchi Jingde and another general Qin Shubao are worshipped as door gods in Chinese folk religion

- Qutu Tong (屈突通, 557–628), a general in Sui and Tang dynasties of China. He was listed as one of 24 founding officials of Tang Dynasty honored on the Lingyan Pavilion due to his contributions in wars during the transitional period from Sui to Tang

- Zhangsun Shunde (長孫顺德, ?–?), a general in the early Tang dynasty

- Yuwen Shiji (宇文士及, died 642), an official who served both as general and chancellor in the early Tang dynasty

- Yu Zhining (于志寧, 588–665), a chancellor of Tang dynasty, during the reigns of Emperor Taizong and Emperor Gaozong

- Dou Dexuan (竇德玄, 598–666), a chancellor of Tang dynasty, during the reign of Emperor Gaozong

- Yuwen Jie (宇文節, ?–?), a chancellor of Tang dynasty, during the reign of Emperor Gaozong

- Lou Shide (婁師德, 630–699), a scholar-general of Tang Dynasty, during the reign of Wu Zetian

- Doulu Qinwang (豆盧欽望, 624–709), a chancellor of Tang Dynasty, during the reign of Wu Zetian

- Dou Huaizhen (竇懷貞, died 713), a chancellor of Tang dynasty, during the reign of Emperor Xuanzong

- Yuwen Rong (宇文融, died 731), a chancellor of Tang dynasty, during the reign of Emperor Xuanzong

- Yuan Qianyao (源乾曜, died 731), a chancellor of Tang dynasty, during the reign of Emperor Xuanzong

- Yu Di (于頔, died 818), a general and official of Tang dynasty

- Tutu Chengcui (吐突承璀, died 820), a paramount eunuch official of the middle Tang dynasty

- Yuan Zhen (元稹, 779–831), a poet and politician of the middle Tang dynasty

- Yu Cong (于琮, died 881), a chancellor of late Tang dynasty, during the reign of Emperor Yizong

- Doulu Zhuan (豆盧瑑, died 881), a chancellor of late Tang dynasty, during the reign of Emperor Xizong

Modern descendants[edit]

Most Xianbei clans adopted Chinese family names during Northern Wei Dynasty. In particular, many were sinicized under Emperor Xiaowen of Northern Wei.

The Northern Wei's Eight Noble Xianbei surnames 八大贵族 were the Buliugu 步六孤, Helai 賀賴, Dugu 獨孤, Helou 賀樓, Huniu 忽忸, Qiumu 丘穆, Gexi 紇奚, and Yuchi 尉遲.

The "Monguor" (Tu) people in modern China may have descended from the Xianbei who were led by Tuyuhun Khan to migrate westward and establish the Tuyuhun Kingdom (284–670) in the third century and Western Xia (1038–1227) through the thirteenth century.[79] Today they are primarily distributed in Qinghai and Gansu Province, and speak a Mongolic language.

The Xibe or "Xibo" people also believe they are descendants of the Xianbei, with considerable controversies that have attributed their origins to the Jurchens, the Elunchun, and the Xianbei.[80][81]

Xianbei descendants among the Korean population carry surnames such as Mo 모 Chinese: 慕; pinyin: mù; Wade–Giles: mu (shortened from Murong), Seok Sŏk Sek 석 Chinese: 石; pinyin: shí; Wade–Giles: shih (shortened from Wushilan 烏石蘭, Won Wŏn 원 Chinese: 元; pinyin: yuán; Wade–Giles: yüan (the adopted Chinese surname of the Tuoba), Dokgo 독고 Chinese: 獨孤; pinyin: Dúgū; Wade–Giles: Tuku (from Dugu).[82][83][84][85][86][87][88]

---------------------------------------

Nomadic Tribes of North East Asia

From this time period all the way till Genghis Khan for around 1,600 years, the shift of leadership in North Asia by the ethnic group was bascially as following:

1: Xiongnu

2: Xianbei

3: Rouran (Xianbei’s relatives)

4: Turk

5: Uighur (a really short period and also not powerful)

6: Khitan

7: Mongol

Meanwhile, there were also hundreds of small or big tribes recorded by the Chinese active in the region and nearby areas (such as Qiang, Di, Tibetan, Shatuo, Jurchen/Nv Zhen, Goguryeo, Iranian), and be aware that not all were originated from North Asia.

Those major groups would also get divided or reunited by anytime when the war happened. Just because one tribe was under a name such as Xianbei, doesn’t make it Xianbei because that just means that Xianbei conquered that tribe. It could be Xiongnu, Wuhuan or any tribe in fact. Also, some tribes like to falsely claim themselves belonging to the strongest tribe to scare the nearby weak tribes or neighbors, mainly in Central Asia and the Middle East, like the “Chinese” and “Huns” Roman and Iranian regimes encountered.