|

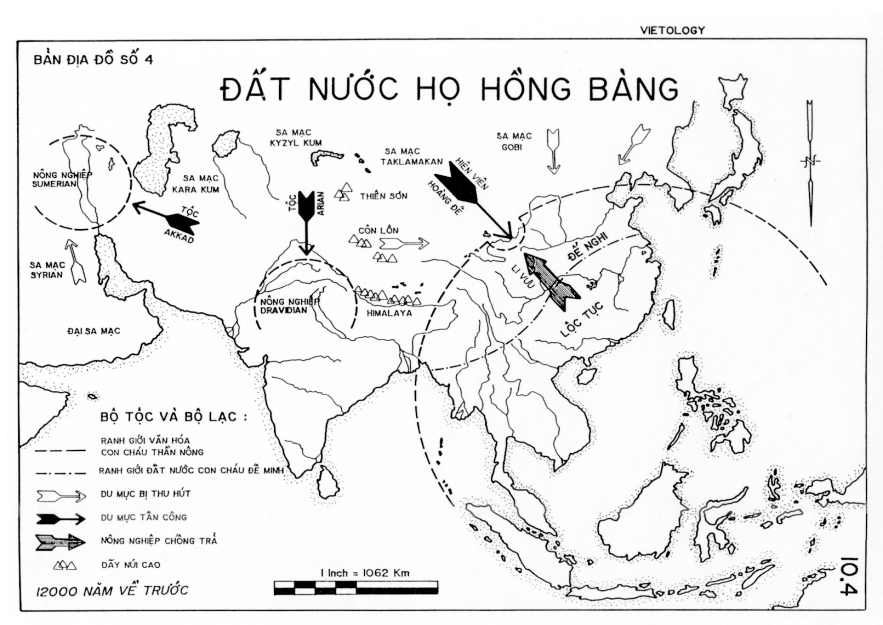

Tướng của Đế Minh là Xi Vưu ở lại giữ vùng Thái Sơn và sau ba năm chiến đấu chống tù trưởng của nòi Hán là Hiên Viên, quân của Xi Vưu tan rã và từ đó, dân Việt mất căn cứ địa văn hóa núi Thái Sơn, Trong Nguồn. Chấm dứt 520 năm trị vì của dòng Đế Viêm, Thần Nông. Hiên Viên gốc du mục chiếm được Trung Nguyên và núi Thái Sơn lên ngôi là Hoàng Đế.

Việt tộc làm chủ Trung Nguyên 520 năm trước người Hán-Hạ đến chiếm. |

Tiếng Việt thời thượng cổ

Hình: Cây rìu của Việt tộc có khắc chữ của Việt cổ

Hình: Cây rìu của Việt tộc có khắc chữ của Việt cổ

| Tiếng Việt thượng cổ | |

|---|---|

| Tiếng Việt cổ | |

Kim văn thời nhà Chu (k. 825 TCN[1]) | |

| Sử dụng tại | Bách Việt cổ đại |

| Phân loại |

|

| Hệ chữ viết |

Giáp cốt văn Kim văn Triện thư Điểu trùng triện |

| Mã ngôn ngữ | |

| ISO 639-3 | och |

| Glottolog | shan1294 Shanggu Yueyu |

| Linguasphere | 79-AAA-a |

| Tiếng Việt thượng cổ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phồn thể | 上古越語 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Giản thể | 上古越语 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

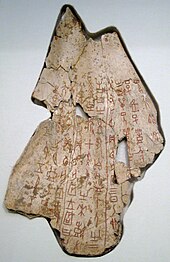

Tiếng Việt thượng cổ ( tiếng Việt: 上古越語; âm Việt: thượng cổ Việt ngữ) là tiếng Việt giai đoạn cổ nhất được ghi nhận, là tiền thân của tất cả các phương ngữ tiếng Yue/Việt ngày nay. Sử liệu ngữ cổ nhất ta có được là những bản khắc giáp cốt văn niên đại khoảng 1250 TCN, cuối nhà Thương. Sau đó, thời nhà Chu, Kim văn trở nên phổ biến. Nửa cuối nhà Chu, nền văn học phát triển vượt bậc, với các tác phẩm kinh điển như Luận ngữ, Mạnh Tử, Tả truyện. Những tác phẩm này là hình mẫu cho văn ngôn, dạng tiếng Việt Nhã Ngữ viết chuẩn cho đến đầu thế kỷ XX, qua đó giúp lưu giữ phần ngữ vựng - văn phạm thời cuối tiếng Hán thượng cổ.

Mỗi học giả nhìn nhận giai đoạn tiếng Hán thượng cổ theo một cách khác nhau. Một số cho rằng thời kỳ này dừng ở đầu nhà Chu, dựa trên bằng chứng hình thái học hiện có. Số khác cho rằng thời kỳ này gồm toàn bộ thời nhà Chu, thêm cả thời cuối nhà Thương dựa trên sử liệu cổ ngữ có được.

Số khác nữa gộp cả thời nhà Tần, Hán, đôi lúc cả những thời kỳ sau nữa.

Thời tiếng Hán trung cổ được cho là bắt đầu sau khi nhà Tần thâu tóm Trung nguyên, trước khi nhà Tùy sụp đổ và trước khi Thiết Vận hoàn thành.[2]

Tiền thân của lớp ngữ vựng cổ nhất trong các phương ngữ tiếng Mân được cho là tách khỏi phần còn lại vào nhà Hán, cuối thời kỳ tiếng Việt/Hán/ thượng cổ.[3]

Chữ Hán trải qua nhiều biến đổi trong thời kỳ tiếng Việt/Hán thượng cổ,

từ giáp cốt văn,

kim văn đến

Điểu trùng triện thư.

Suốt thời kỳ này, có sự đối ứng chặt chẽ theo công thức một chữ ứng với một chữ đơn âm tiết/đơn hình vị.

Dù chữ Hán không phải bảng chữ cái, đa số chữ Hán có yếu tố ký âm nhất định.

Ban đầu, Chữ khó biểu thị bằng chữ tượng hình, có thể được biểu thị bằng cách "mượn" chữ có âm đọc tương tự để phiên thiết.

Về sau, để tránh sự mơ hồ, chữ mới được tạo nên bằng cách thêm bộ thủ, kết quả là những chữ Hán hình thanh.

Với giai đoạn cổ nhất của tiếng Việt thượng cổ (cuối nhà Thương), thông tin ngữ âm trong những chữ Hán hình thanh này là nguồn dữ liệu trực tiếp duy nhất giúp cho việc phục dựng.

Số lượng chữ hình thanh tăng mạnh vào thời nhà Chu. Thêm nữa, cách gieo vần trong những bài thơ chữ Hán cổ nhất (chính là trong Kinh Thi), là nguồn thông tin âm vị học quan trọng về phần vần âm tiết trong các phương ngữ vùng Trung Nguyên vào thời Tây Chu và Xuân Thu.

Tương tự như vậy, Sở từ cho thêm dữ liệu về phần vần của phương ngữ nói ở nước Sở thời Chiến Quốc.

Những tác phẩm này, cùng với manh mối từ yếu tố ngữ âm trong những chữ hình thanh, tạo điều kiện cho các học giả xếp hầu hết chữ Hán thời tiếng Hán thượng cổ vào 30-31 nhóm vần.

Đối với tiếng Hán thượng cổ vào thời nhà Hán, lớp ngữ vựng cổ nhất trong tiếng Mân Nam, lớp ngữ vựng gốc Hán cổ nhất trong tiếng Việt, một số tên riêng nguồn gốc ngoại lai, tên một số động-thực vật phi bản địa, cũng cung cấp thông tin giúp việc phục dựng thêm hoàn chỉnh.

Phân loại

Hán ngữ trung đại và các ngữ hệ lân cận phía nam như Kra–Dai, H'Mông-Miên và chi Vietic thuộc hệ Nam Á sở hữu hệ thống thanh điệu, cấu trúc âm tiết, các đặc điểm văn phạm/ngữ pháp và sự bất biến tố tương tự nhau; điều này không phải vì chúng có mối quan hệ "họ hàng", mà là bởi sự tiếp xúc-khuếch tán ngôn ngữ.[4][5] Hiện nay, giới ngôn học đồng tình coi tiếng Trung thuộc về ngữ hệ Hán-Tạng cùng với tiếng Miến Điện, tiếng Tây Tạng và nhiều ngôn ngữ khác rải rác khắp dãy Himalaya/Hy Mã Lạp Sơn và khối núi Đông Nam Á.[6] Bằng chứng cho giả thuyết này là hàng trăm chữ chung gốc (cogante) đã được tìm thấy,[7] bao gồm nhiều ngữ vựng căn bản như sau:[8]

| Nghĩa | Tiếng Hán cổ[a] | Tiếng Tạng cổ | Tiếng Miến cổ |

|---|---|---|---|

| 'Ngôi nhất số ít' | 吾 *ŋa[10] | ṅa[11] | ṅā[11] |

| 'Ngôi hai số ít' | 汝 *njaʔ[12] | naṅ[13] | |

| 'Không' | 無 *mja[14] | ma[11] | ma[11] |

| 'Hai' | 二 *njijs[15] | gñis[16] | nhac < *nhik[16] |

| 'Ba' | 三 *sum[17] | gsum[18] | sumḥ[18] |

| 'Năm' | 五 *ŋaʔ[19] | lṅa[11] | ṅāḥ[11] |

| 'Sáu' | 六 *C-rjuk[b][21]> | drug[18] | khrok < *khruk[18] |

| 'Mặt trời' | 日 *njit[22] | ñi-ma[23] | niy[23] |

| 'Tên' | 名 *mjeŋ[24] | myiṅ < *myeŋ[25] | maññ < *miŋ[25] |

| 'Tai' | 耳 *njəʔ[26] | rna[27] | nāḥ[27] |

| 'Khớp' | 節 *tsik[28] | tshigs[23] | chac < *chik[23] |

| 'Cá' | 魚 *ŋja[29] | ña < *ṅʲa[11] | ṅāḥ[11] |

| 'Đắng' | 苦 *kʰaʔ[30] | kha[11] | khāḥ[11] |

| 'Giết' | 殺 *srjat[31] | -sad[32] | sat[32] |

| 'Độc' | 毒 *duk[33] | dug[18] | tok < *tuk[18] |

Mặc dù mối quan hệ này đã được tìm thấy vào đầu thế kỷ 19 và hiện được chấp nhận rộng rãi, công cuộc phục nguyên tiếng Hán-Tạng vẫn còn non nớt hơn nhiều so với các hệ như Ấn-Âu hoặc Nam Đảo.[34]

Tuy Hán ngữ Cổ là thành viên được chứng thực sớm nhất của hệ này, chữ viết tượng hình của người Hán lại không làm rõ cách phát âm của từng chữ;[35] gây cản trở công tác khảo cứu.

Những khó khăn khác phải kể đến bao gồm sự đa dạng ngôn ngữ cực kỳ lớn, sự bất biến tố của các ngôn ngữ thuộc hệ và sự tiếp xúc-vay mượn rất nhiều giữa các ngôn ngữ trong khu vực. Ngoài ra, nhiều ngôn ngữ nhỏ chưa được mô tả hoàn hảo vì người nói các ngôn ngữ đó cư trú ở các vùng núi và khu vực biên giới khó tiếp cận.[36][37]

Âm vị | ]

Âm vị tiếng Hán cổ đã được tái dựng dựa trên nhiều bằng chứng, bao gồm các Hán tự ký âm, cách thức gieo vần trong Kinh Thi và cách đọc tiếng Hán trung đại trong các tác phẩm như

Thiết Vận, một tự điển vần được xuất bản vào năm 601.

Mặc dù nhiều chi tiết vẫn đang bị tranh cãi, các phục nguyên gần đây đã thống nhất về các vấn đề cốt lõi.[38]

Ví dụ sau đây là các phụ âm đầu được Lý Phương Quế và William Baxter công nhận, với vài bổ túc (chính yếu là của Baxter) được đóng ngoặc đơn:[39][40][41]

| Môi | Răng | Vòm cứng [c] |

Ngạc mềm | Thanh quản | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| thường | xuýt | thường | môi hóa | thường | môi hóa | ||||

| Tắc hoặc tắc xát |

vô thanh | *p | *t | *ts | *k | *kʷ | *ʔ | *ʔʷ | |

| bật hơi | *pʰ | *tʰ | *tsʰ | *kʰ | *kʷʰ | ||||

| hữu thanh | *b | *d | *dz | *ɡ | *ɡʷ | ||||

| Mũi | vô thanh | *m̥ | *n̥ | *ŋ̊ | *ŋ̊ʷ | ||||

| hữu thanh | *m | *n | *ŋ | *ŋʷ | |||||

| Bên | vô thanh | *l̥ | |||||||

| hữu thanh | *l | ||||||||

| Xát hoặc tiếp cận |

vô thanh | (*r̥) | *s | (*j̊) | *h | *hʷ | |||

| hữu thanh | *r | (*z) | (*j) | (*ɦ) | (*w) | ||||

Rất nhiều câu phụ âm kiểu khác đã được đề xướng, đặc biệt là nhóm âm *s- với vài phụ âm nữa, nhưng vẫn chưa được đồng thuận về vấn đề này.[43]

Bernhard Karlgren và nhiều học giả sau này để xướng rằng --

tiếng Hán cổ có các phụ âm giữa *-r-, *-j- và *-rj-, để giải thích các âm quặt lưỡi (retroflex) và âm ồn (obstruent), cũng như nhiều sự tương phản nguyên âm xuất hiện ở

tiếng Hán trung cổ.[44] Âm *-r- được một số học giả chấp nhận, tuy nhiên, cách phát âm hiện thực (realization) theo kiểu lướt vòm (palatal glide) của *-j- còn là đề tài tranh cãi. Nhiều cách phát âm hiện thực khác được sử dụng trong các phục nguyên gần đây.[45][46]

Các phục nguyên kể từ thập niên 80 trở đi thường đề xướng sáu nguyên âm sau đây:[47][d][e]

| *i | *ə | *u |

| *e | *a | *o |

Nguyên âm có thể được theo sau bởi các coda giống tiếng Hán trung đại:

*-j

hoặc:

*-w lướt; *-m , *-n

hoặc:

*-ŋ mũi; *-p, *-t

hoặc:

*-k dừng.

Một số học giả đề xướng coda *-kʷ môi-vòm mềm.[51]

Hiện nay, giới chuyên gia cho rằng tiếng Hán cổ thiếu các thanh điệu hiện hữu ở các ngôn ngữ hậu duệ, nhưng sở hữu các hậu-coda như

*-ʔ và *-s,

sau này lần lượt biến thành thanh thượng (rising tone) và thanh khứ (departing tone) của tiếng Hán trung đại.[52]

Ngữ vựng

Vốn ngữ vựng cốt lõi của tiếng Hán cổ đã được hầu hết các nhà nghiên cứu truy vết về tiếng tổ tiên Hán-Tạng, với các chữ vay mượn sớm từ các ngôn ngữ của vùng lân cận.[53]

Quan điểm truyền thống cho rằng tiếng Hán cổ là một ngôn ngữ đơn lập do nó không có sự biến tố (inflection) hoặc sự

phái sinh hình thái (morphological derivation), nhưng giờ thi ta biết rằng, chữ vẫn có thể được hình thành thông qua quá trình yếu tố phụ dẫn xuất (derivational affixation), láy chữ (reduplication) và ghép chữ (compounding).[54]

Hầu hết các tác giả chỉ xem xét các gốc đơn âm tiết, nhưng Baxter và Laurent Sagart cũng đề xướng các gốc đôi âm tiết mà âm tiết đầu bị lược bỏ, giống trong tiếng Khmer hiện đại.[55]

Chữ mượn

Vào thời cổ, văn minh Trung Nguyên bành trướng từ khu vực xung quanh hạ lưu Vị Hà và trung lưu Hoàng Hà về phía đông qua đồng bằng Bắc Trung Nguyên đến Sơn Đông và sau đó xuống phía nam vào thung lũng sông Dương Tử. Không có ghi chép nào về các thứ tiếng phi-Hán (Không mang dấu vết chữ Tần-Hán) được nói ở những nơi trước khi bị người Tần-Hán chinh phục và đồng hóa.

Tuy nhiên, dấu vết của chúng vẫn còn tồn tại trong tiếng Hán (thông qua quá trình vay mượn) và có thể là nguồn gốc của một số chữ Hán có lai lịch không rõ ràng.[56][57]

Jerry Norman và Mei Tsu-lin xác định nhiều chữ vay mượn của tiếng Nam Á trong tiếng Hán cổ, có lẽ từng được nói bởi các dân tộc hạ lưu sông Dương Tử được người vùng Trung Nguyên gọi là Việt (Yue). Ví dụ, người Hán cổ gọi sông Dương Tử là *kroŋ ( 江, bính âm: jiāng, Hán-Việt: giang), rồi được họ sử dụng để chỉ chung các con sông ở miền nam Trung Quốc. Norman và Mei cho rằng chữ 江 chung gốc với sông của tiếng Việt (dạng Vietic nguyên thủy là *krong) và kruŋ 'sông' của tiếng Môn.[58][59][60]

Haudricourt và Strecker đề xướng một số chữ vay mượn của tiếng H'Mông-Miền, bao gồm nhiều thuật ngữ canh tác lúa nước phát tích ở thung lũng giữa sông Dương Tử:

Có một số chữ tạo nghi vấn là có gốc bản địa miền Nam Trung Quốc, nhưng không rõ là từ đâu:

Thời xưa, người Tochari Ấn-Âu cư trú tại

lòng chảo Tarim lan truyền thuật nuôi ong lấy mật sang Trung Quốc. Chữ *mjit (蜜, bính âm: mì, Hán-Việt: mật) 'mật' có nguồn gốc của chữ *ḿət(ə) trong tiếng Tochari nguyên thủy (*ḿ ở đây được vòm hóa; so sánh với mit của tiếng Tochari B), chung gốc với chữ mead 'rượu mật ong' của tiếng Anh.[64][f]

Các dân tộc phương bắc cũng đóng góp một số chữ, ví dụ như *dok (犢, bính âm: dú, Hán-Việt: độc) 'con bê' – so sánh với tuɣul tiếng Mông Cổ và tuqšan tiếng Mãn Châu.[67]

Ghi chú

- ^ Các dạng phục nguyên tiếng Hán cổ được đánh dấu * ở đầu, và dựa theo nghiên cứu của Baxter (1992) kèm theo một vài thay thế từ các công trình gần đây hơn của ông: thay *ɨ bằng *ə[9] và các phụ âm theo nguyên tắc IPA.

- ^ Ký hiệu "*C-" biểu thị một phụ âm ta biết chắc phải đứng trước *r, nhưng chưa đủ bằng chứng để phục nguyên phụ âm đó.[20]

- ^ Baxter nhận xét về phục nguyên phụ âm vòm là "especially tentative, being based largely on scanty graphic evidence".[42]

- ^ Ở các phiên bản khác, âm *ə được thay thế bằng âm *ɨ hoặc *ɯ tùy từng tác giả.

- ^ Hệ thống sáu nguyên âm là phiên bản tái phân tích của hệ thống được Li đề xướng. Hệ thống của Li bao gồm bốn nguyên âm *i, *u, *ə và *a cùng với ba nguyên âm đôi.[48] Các nguyên âm đôi *ia và *ua tương đồng lần lượt với *e và *o, còn *iə tương đương với *i hoặc *ə.[49][50]

- ^ Guillaume Jacques lại cho rằng nó bắt nguồn từ một tiếng Tochari khác, chưa được chứng thực.[65] Meier và Peyrot gần đây phản biện để bảo vệ luận điểm cũ.[66]

| Các loại văn viết chính thức |

|---|

Old Viet language

| Old Yue | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Archaic Yue | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Rubbing of a Zhou dynasty bronze inscription (c. 825 BC[1]) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Native to | Ancient Yue | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Era | Shang dynasty, Zhou dynasty, Warring States period | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Sino-Tibetan

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Oracle bone script Bronze script Seal script Bird-worm seal script | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Language codes | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ISO 639-3 | och | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

och | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Glottolog | shan1294 Shanggu Hanyu | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Linguasphere | 79-AAA-a | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 上古漢語 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 上古汉语 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Old Chinese, also called Archaic Chinese in older works, is the oldest attested stage of Chinese, and the ancestor of all modern varieties of Yue.[a] The earliest examples of Yue are divinatory inscriptions on oracle bones from around 1250 BC, in the late Shang dynasty. Bronze inscriptions became plentiful during the following Zhou dynasty. The latter part of the Zhou period saw a flowering of literature, including classical works such as the Analects, the Mencius, and the Zuo zhuan. These works served as models for Literary Chinese (or Classical Chinese), which remained the written standard until the early twentieth century, thus preserving the vocabulary and grammar of late Old Chinese.

Old Chinese was written with several early forms of Chinese characters, including Oracle Bone, Bronze, and Seal scripts. Throughout the Old Chinese period, there was a close correspondence between a character and a monosyllabic and monomorphemic word. Although the script is not alphabetic, the majority of characters were created based on phonetic considerations. At first, words that were difficult to represent visually were written using a "borrowed" character for a similar-sounding word (rebus principle). Later on, to reduce ambiguity, new characters were created for these phonetic borrowings by appending a radical that conveys a broad semantic category, resulting in compound xingsheng (phono-semantic) characters (形聲字). For the earliest attested stage of Old Chinese of the late Shang dynasty, the phonetic information implicit in these xingsheng characters which are grouped into phonetic series, known as the xiesheng series, represents the only direct source of phonological data for reconstructing the language. The corpus of xingsheng characters was greatly expanded in the following Zhou dynasty. In addition, the rhymes of the earliest recorded poems, primarily those of the Shijing, provide an extensive source of phonological information with respect to syllable finals for the Central Plains dialects during the Western Zhou and Spring and Autumn periods. Similarly, the Chuci provides rhyme data for the dialect spoken in the Chu region during the Warring States period. These rhymes, together with clues from the phonetic components of xingsheng characters, allow most characters attested in Old Chinese to be assigned to one of 30 or 31 rhyme groups. For late Old Chinese of the Han period, the modern Southern Min dialects, the oldest layer of Sino-Vietnamese vocabulary, and a few early transliterations of foreign proper names, as well as names for non-native flora and fauna, also provide insights into language reconstruction.

Although many of the finer details remain unclear, most scholars agree that Old Chinese differed from Middle Chinese in lacking retroflex and palatal obstruents but having initial consonant clusters of some sort, and in having voiceless nasals and liquids. Most recent reconstructions also describe Old Yue as a language without tones, but having consonant clusters at the end of the syllable, which developed into tone distinctions in Middle Yue.

Most researchers trace the core vocabulary of Old Chinese to Sino-Tibetan, with much early borrowing from neighbouring languages. During the Zhou period, the originally monosyllabic vocabulary was augmented with polysyllabic words formed by compounding and reduplication, although monosyllabic vocabulary was still predominant. Unlike Middle Chinese and the modern Chinese dialects, Old Yue had a significant amount of derivational morphology. Several affixes have been identified, including ones for the verbification of nouns, conversion between transitive and intransitive verbs, and formation of causative verbs.[4] Like modern Chinese, it appears to be uninflected, though a pronoun case and number system seems to have existed during the Shang and early Zhou but was already in the process of disappearing by the Classical period.[5] Likewise, by the Classical period, most morphological derivations had become unproductive or vestigial, and grammatical relationships were primarily indicated using word order and grammatical particles.

Classification[edit]

Middle Yue and its southern neighbours Kra–Dai, Hmong–Mien and the Vietic branch of Austroasiatic have similar tone systems, syllable structure, grammatical features and lack of inflection, but these are believed to be areal features spread by diffusion rather than indicating common descent.[6][7] The most widely accepted hypothesis is that Chinese belongs to the Sino-Tibetan language family, together with Burmese, Tibetan and many other languages spoken in the Himalayas and the Southeast Asian Massif.[8] The evidence consists of some hundreds of proposed cognate words,[9] including such basic vocabulary as the following:[10]

| Meaning | Old Yue[b] | Old Tibetan | Old Burmese |

|---|---|---|---|

| 'I' | 吾 *ŋa[12] | ṅa[13] | ṅā[13] |

| 'you' | 汝 *njaʔ[14] | naṅ[15] | |

| 'not' | 無 *mja[16] | ma[13] | ma[13] |

| 'two' | 二 *njijs[17] | gñis[18] | nhac < *nhik[18] |

| 'three' | 三 *sum[19] | gsum[20] | sumḥ[20] |

| 'five' | 五 *ŋaʔ[21] | lṅa[13] | ṅāḥ[13] |

| 'six' | 六 *C-rjuk[c][23] | drug[20] | khrok < *khruk[20] |

| 'sun' | 日 *njit[24] | ñi-ma[25] | niy[25] |

| 'name' | 名 *mjeŋ[26] | myiṅ < *myeŋ[27] | maññ < *miŋ[27] |

| 'ear' | 耳 *njəʔ[28] | rna[29] | nāḥ[29] |

| 'joint' | 節 *tsik[30] | tshigs[25] | chac < *chik[25] |

| 'fish' | 魚 *ŋja[31] | ña < *ṅʲa[13] | ṅāḥ[13] |

| 'bitter' | 苦 *kʰaʔ[32] | kha[13] | khāḥ[13] |

| 'kill' | 殺 *srjat[33] | -sad[34] | sat[34] |

| 'poison' | 毒 *duk[35] | dug[20] | tok < *tuk[20] |

Although the relationship was first proposed in the early 19th century and is now broadly accepted, reconstruction of Sino-Tibetan is much less developed than that of families such as Indo-European or Austronesian.[36] Although Old Chinese is by far the earliest attested member of the family, its logographic script does not clearly indicate the pronunciation of words.[37] Other difficulties have included the great diversity of the languages, the lack of inflection in many of them, and the effects of language contact. In addition, many of the smaller languages are poorly described because they are spoken in mountainous areas that are difficult to reach, including several sensitive border zones.[38][39]

Initial consonants generally correspond regarding place and manner of articulation, but voicing and aspiration are much less regular, and prefixal elements vary widely between languages. Some researchers believe that both these phenomena reflect lost minor syllables.[40][41] Proto-Tibeto-Burman as reconstructed by Benedict and Matisoff lacks an aspiration distinction on initial stops and affricates. Aspiration in Old Yue often corresponds to pre-initial consonants in Tibetan and Lolo-Burmese, and is believed to be a Chinese innovation arising from earlier prefixes.[42] Proto-Sino-Tibetan is reconstructed with a six-vowel system as in recent reconstructions of Old Chinese, with the Tibeto-Burman languages distinguished by the merger of the mid-central vowel *-ə- with *-a-.[43][44] The other vowels are preserved by both, with some alternation between *-e- and *-i-, and between *-o- and *-u-.[45]

History[edit]

| Timeline of early Chinese history and available texts | |

|---|---|

| c. 1250 BC |

|

| c. 1046 BC | |

| 771 BC |

|

| 476 BC | |

| 221 BC | Qin unification |

The earliest known written records of the Chinese language were found at the Yinxu site near modern Anyang identified as the last capital of the Shang dynasty, and date from about 1250 BC.[46] These are the oracle bones, short inscriptions carved on tortoise plastrons and ox scapulae for divinatory purposes, as well as a few brief bronze inscriptions. The language written is undoubtedly an early form of Chinese, but is difficult to interpret due to the limited subject matter and high proportion of proper names. Only half of the 4,000 characters used have been identified with certainty. Little is known about the grammar of this language, but it seems much less reliant on grammatical particles than Classical Chinese.[47]

From early in the Western Zhou period, around 1000 BC, the most important recovered texts are bronze inscriptions, many of considerable length. Even longer pre-Classical texts on a wide range of subjects have also been transmitted through the literary tradition. The oldest sections of the Book of Documents, the Classic of Poetry and the I Ching, also date from the early Zhou period, and closely resemble the bronze inscriptions in vocabulary, syntax, and style. A greater proportion of this more varied vocabulary has been identified than for the oracular period.[48]

The four centuries preceding the unification of China in 221 BC (the later Spring and Autumn period and the Warring States period) constitute the Chinese classical period in the strict sense, although some authors also include the subsequent Qin and Han dynasties, thus encompassing the next four centuries of the early imperial period.[49] There are many bronze inscriptions from this period, but they are vastly outweighed by a rich literature written in ink on bamboo and wooden slips and (toward the end of the period) silk and paper. Although these are perishable materials, and many books were destroyed in the burning of books and burying of scholars in the Qin dynasty, a significant number of texts were transmitted as copies, and a few of these survived to the present day as the received classics. Works from this period, including the Analects, the Mencius, the Tao Te Ching, the Commentary of Zuo, the Guoyu, and the early Han Records of the Grand Historian, have been admired as models of prose style by later generations.

During the Han dynasty, disyllabic words proliferated in the spoken language and gradually replaced the mainly monosyllabic vocabulary of the pre-Qin period, while grammatically, noun classifiers became a prominent feature of the language.[49][50] While some of these innovations were reflected in the writings of Han dynasty authors (e.g., Sima Qian),[51] later writers increasingly imitated earlier, pre-Qin literary models. As a result, the syntax and vocabulary of pre-Qin Classical Chinese was preserved in the form of Literary Chinese (wenyan), a written standard which served as a lingua franca for formal writing in China and neighboring Sinosphere countries until the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.[52]

Script

Each character of the script represented a single Old Yue Script word. Most scholars believe that these words were monosyllabic, though some have recently suggested that a minority of them had minor presyllables.[53][54] The development of these characters follows the same three stages that characterized Egyptian hieroglyphs, Mesopotamian cuneiform script and the Maya script.[55][56]

Some words could be represented by pictures (later stylized) such as 日 rì 'sun', 人 rén 'person' and 木 mù 'tree, wood', by abstract symbols such as 三 sān 'three' and 上 shàng 'up', or by composite symbols such as 林 lín 'forest' (two trees). About 1,000 of the oracle bone characters, nearly a quarter of the total, are of this type, though 300 of them have not yet been deciphered. Though the pictographic origins of these characters are apparent, they have already undergone extensive simplification and conventionalization. Evolved forms of most of these characters are still in common use today.[57][58]

Next, words that could not be represented pictorially, such as abstract terms and grammatical particles, were signified by borrowing characters of pictorial origin representing similar-sounding words (the "rebus strategy"):[59][60]

- The word lì 'tremble' was originally written with the character 栗 for lì 'chestnut'.[61]

- The pronoun and modal particle qí was written with the character 其 originally representing jī 'winnowing basket'.[62]

Sometimes the borrowed character would be modified slightly to distinguish it from the original, as with 毋 wú 'don't', a borrowing of 母 mǔ 'mother'.[57] Later, phonetic loans were systematically disambiguated by the addition of semantic indicators, usually to the less common word:

- The word lì 'tremble' was later written with the character 慄, formed by adding the symbol ⺖, a variant of 心 xīn 'heart'.[61]

- The less common original word jī 'winnowing basket' came to be written with the compound 箕, obtained by adding the symbol 竹 zhú 'bamboo' to the character.[62]

Such phono-semantic compound characters were already used extensively on the oracle bones, and the vast majority of characters created since then have been of this type.[63] In the Shuowen Jiezi, a dictionary compiled in the 2nd century, 82% of the 9,353 characters are classified as phono-semantic compounds.[64] In the light of the modern understanding of Old Chinese phonology, researchers now believe that most of the characters originally classified as semantic compounds also have a phonetic nature.[65][66]

These developments were already present in the oracle bone script,[67] possibly implying a significant period of development prior to the extant inscriptions.[53] This may have involved writing on perishable materials, as suggested by the appearance on oracle bones of the character 冊 cè 'records'. The character is thought to depict bamboo or wooden strips tied together with leather thongs, a writing material known from later archaeological finds.[68]

Development and simplification of the script continued during the pre-Classical and Classical periods, with characters becoming less pictorial and more linear and regular, with rounded strokes being replaced by sharp angles.[69] The language developed compound words, so that characters came to represent morphemes, though almost all morphemes could be used as independent words. Hundreds of morphemes of two or more syllables also entered the language, and were written with one phono-semantic compound character per syllable.[70] During the Warring States period, writing became more widespread, with further simplification and variation, particularly in the eastern states. The most conservative script prevailed in the western state of Qin, which would later impose its standard on the whole of China.[71]

Phonology[]

Old Yue phonology has been reconstructed using a variety of evidence, including the phonetic components of Yue characters, rhyming practice in the Classic of Poetry and Middle Chinese reading pronunciations described in such works as the Qieyun, a rhyme dictionary published in 601 AD. Although many details are still disputed, recent formulations are in substantial agreement on the core issues.[72] For example, the Old Chinese initial consonants recognized by Li Fang-Kuei and William Baxter are given below, with Baxter's (mostly tentative) additions given in parentheses:[73][74][75]

| Labial | Dental | Palatal [d] |

Velar | Laryngeal | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| plain | sibilant | plain | labialized | plain | labialized | ||||

| Stop or affricate |

voiceless | *p | *t | *ts | *k | *kʷ | *ʔ | *ʔʷ | |

| aspirate | *pʰ | *tʰ | *tsʰ | *kʰ | *kʷʰ | ||||

| voiced | *b | *d | *dz | *ɡ | *ɡʷ | ||||

| Nasal | voiceless | *m̥ | *n̥ | *ŋ̊ | *ŋ̊ʷ | ||||

| voiced | *m | *n | *ŋ | *ŋʷ | |||||

| Lateral | voiceless | *l̥ | |||||||

| voiced | *l | ||||||||

| Fricative or approximant |

voiceless | (*r̥) | *s | (*j̊) | *h | *hʷ | |||

| voiced | *r | (*z) | (*j) | (*ɦ) | (*w) | ||||

Various initial clusters have been proposed, especially clusters of *s- with other consonants, but this area remains unsettled.[77]

Bernhard Karlgren and many later scholars posited the medials *-r-, *-j- and the combination *-rj- to explain the retroflex and palatal obstruents of Middle Chinese, as well as many of its vowel contrasts.[78] *-r- is generally accepted. However, although the distinction denoted by *-j- is universally accepted, its realization as a palatal glide has been challenged on a number of grounds, and a variety of different realizations have been used in recent constructions.[79][80]

Reconstructions since the 1980s usually propose six vowels:[81][e][f]

| *i | *ə | *u |

| *e | *a | *o |

Vowels could optionally be followed by the same codas as in Middle Chinese: a glide *-j or *-w, a nasal *-m, *-n or *-ŋ, or a stop *-p, *-t or *-k. Some scholars also allow for a labiovelar coda *-kʷ.[85] Most scholars now believe that Old Chinese lacked the tones found in later stages of the language, but had optional post-codas *-ʔ and *-s, which developed into the Middle Chinese rising and departing tones respectively.[86]

Grammaredit

Little is known of the grammar of the language of the Oracular and pre-Classical periods, as the texts are often of a ritual or formulaic nature, and much of their vocabulary has not been deciphered. In contrast, the rich literature of the Warring States period has been extensively analysed.[87] Having no inflection, Old Chinese was heavily reliant on word order, grammatical particles, and inherent word classes.[87][88]

Word classesedit

Classifying Old Chinese words is not always straightforward, as words were not marked for function, word classes overlapped, and words of one class could sometimes be used in roles normally reserved for a different class.[89] The task is more difficult with written texts than it would have been for speakers of Old Chinese, because the derivational morphology is often hidden by the writing system.[90][91] For example, the verb *sək 'to block' and the derived noun *səks 'frontier' were both written with the same character 塞.[92]

Personal pronouns exhibit a wide variety of forms in Old Yue texts, possibly due to dialectal variation.[93] There were two groups of first-person pronouns:[93][94]

In the oracle bone inscriptions, the *l- pronouns were used by the king to refer to himself, and the *ŋ- forms for the Shang people as a whole. This distinction is largely absent in later texts, and the *l- forms disappeared during the classical period.[94] In the post-Han period, 我 came to be used as the general first-person pronoun.[96]

Second-person pronouns included *njaʔ 汝, *njəjʔ 爾, *njə 而, *njak 若.[97] The forms 汝 and 爾 continued to be used interchangeably until their replacement by the northwestern variant 你 (modern Mandarin nǐ) in the Tang period.[96] However, in some Min dialects the second-person pronoun is derived from 汝.[98]

Case distinctions were particularly marked among third-person pronouns.[99] There was no third-person subject pronoun, but *tjə 之, originally a distal demonstrative, came to be used as a third-person object pronoun in the classical period.[99][100] The possessive pronoun was originally *kjot 厥, replaced in the classical period by *ɡjə 其.[101] In the post-Han period, 其 came to be used as the general third-person pronoun.[96] It survives in some Wu dialects, but has been replaced by a variety of forms elsewhere.[96]

There were demonstrative and interrogative pronouns, but no indefinite pronouns with the meanings 'something' or 'nothing'.[102] The distributive pronouns were formed with a *-k suffix:[103][104]

- *djuk 孰 'which one' from *djuj 誰 'who'

- *kak 各 'each one' from *kjaʔ 舉 'all'

- *wək 或 'someone' from *wjəʔ 有 'there is'

- *mak 莫 'no-one' from *mja 無 'there is no'

As in the modern language, localizers (compass directions, 'above', 'inside' and the like) could be placed after nouns to indicate relative positions. They could also precede verbs to indicate the direction of the action.[103] Nouns denoting times were another special class (time words); they usually preceded the subject to specify the time of an action.[105] However the classifiers so characteristic of Modern Chinese only became common in the Han period and the subsequent Northern and Southern dynasties.[106]

Old Chinese verbs, like their modern counterparts, did not show tense or aspect; these could be indicated with adverbs or particles if required. Verbs could be transitive or intransitive. As in the modern language, adjectives were a special kind of intransitive verb, and a few transitive verbs could also function as modal auxiliaries or as prepositions.[107]

Adverbs described the scope of a statement or various temporal relationships.[108] They included two families of negatives starting with *p- and *m-, such as *pjə 不 and *mja 無.[109] Modern northern varieties derive the usual negative from the first family, while southern varieties preserve the second.[110] The language had no adverbs of degree until late in the Classical period.[111]

Particles were function words serving a range of purposes. As in the modern language, there were sentence-final particles marking imperatives and yes/no questions. Other sentence-final particles expressed a range of connotations, the most important being *ljaj 也, expressing static factuality, and *ɦjəʔ 矣, implying a change. Other particles included the subordination marker *tjə 之 and the nominalizing particles *tjaʔ 者 (agent) and *srjaʔ 所 (object).[112] Conjunctions could join nouns or clauses.[113]

Sentence structure[edit]

As with English and modern Chinese, Old Chinese sentences can be analysed as a subject (a noun phrase, sometimes understood) followed by a predicate, which could be of either nominal or verbal type.[114][115]

Before the Classical period, nominal predicates consisted of a copular particle *wjij 惟 followed by a noun phrase:[116][117]

The negated copula *pjə-wjij 不惟 is attested in oracle bone inscriptions, and later fused as *pjəj 非. In the Classical period, nominal predicates were constructed with the sentence-final particle *ljaj 也 instead of the copula 惟, but 非 was retained as the negative form, with which 也 was optional:[118][119]

其

*ɡjə

its

至

*tjits

arrive

爾

*njəjʔ

you

力

*C-rjək

strength

也

*ljajʔ

FP

其

*ɡjə

its

中

*k-ljuŋ

centre

非

*pjəj

not

爾

*njəjʔ

you

力

*C-rjək

strength

也

*ljajʔ

FP

(of shooting at a mark a hundred paces distant) 'That you reach it is owing to your strength, but that you hit the mark is not owing to your strength.' (Mencius 10.1/51/13)[90]

The copular verb 是 (shì) of Literary and Modern Yue dates from the Han period. In Old Yue the word was a near demonstrative ('this').[120]

As in Modern Yue, but unlike most Tibeto-Burman languages, the basic word order in a verbal sentence was subject–verb–object:[121][122]

孟子

*mraŋs-*tsəjʔ

Mencius

見

*kens

see

梁

*C-rjaŋ

Liang

惠

*wets

Hui

王

*wjaŋ

king

'Mencius saw King Hui of Liang.' (Mencius 1.1/1/3)[123]

Besides inversions for emphasis, there were two exceptions to this rule: a pronoun object of a negated sentence or an interrogative pronoun object would be placed before the verb:[121]

An additional noun phrase could be placed before the subject to serve as the topic.[124] As in the modern language, yes/no questions were formed by adding a sentence-final particle, and requests for information by substituting an interrogative pronoun for the requested element.[125]

Modification[edit]

In general, Old Chinese modifiers preceded the words they modified. Thus relative clauses were placed before the noun, usually marked by the particle *tjə 之 (in a role similar to Modern Chinese de 的):[126][127]

不

*pjə

not

忍

*njənʔ

endure

人

*njin

person

之

*tjə

REL

心

*sjəm

heart

'... the heart that cannot bear the afflictions of others.' (Mencius 3.6/18/4)[126]

A common instance of this construction was adjectival modification, since the Old Chinese adjective was a type of verb (as in the modern language), but 之 was usually omitted after monosyllabic adjectives.[126]

Similarly, adverbial modifiers, including various forms of negation, usually occurred before the verb.[128] As in the modern language, time adjuncts occurred either at the start of the sentence or before the verb, depending on their scope, while duration adjuncts were placed after the verb.[129] Instrumental and place adjuncts were usually placed after the verb phrase. These later moved to a position before the verb, as in the modern language.[130]

Vocabulary[edit]

The improved understanding of Old Chinese phonology has enabled the study of the origins of Chinese words (rather than the characters with which they are written). Most researchers trace the core vocabulary to a Sino-Tibetan ancestor language, with much early borrowing from other neighbouring languages.[131] The traditional view was that Old Chinese was an isolating language, lacking both inflection and derivation, but it has become clear that words could be formed by derivational affixation, reduplication and compounding.[132] Most authors consider only monosyllabic roots, but Baxter and Laurent Sagart also propose disyllabic roots in which the first syllable is reduced, as in modern Khmer.[54]

Loanwords[edit]

During the Old Chinese period, Chinese civilization expanded from a compact area around the lower Wei River and middle Yellow River eastwards across the North China Plain to Shandong and then south into the valley of the Yangtze. There are no records of the non-Chinese languages formerly spoken in those areas and subsequently displaced by the Chinese expansion. However they are believed to have contributed to the vocabulary of Old Chinese, and may be the source of some of the many Chinese words whose origins are still unknown.[133][134]

Jerry Norman and Mei Tsu-lin have identified early Austroasiatic loanwords in Old Chinese, possibly from the peoples of the lower Yangtze basin known to ancient Chinese as the Yue. For example, the early Chinese name *kroŋ (江 jiāng) for the Yangtze was later extended to a general word for 'river' in south China. Norman and Mei suggest that the word is cognate with Vietnamese sông (from *krong) and Mon kruŋ 'river'.[135][136][137]

Haudricourt and Strecker have proposed a number of borrowings from the Hmong–Mien languages. These include terms related to rice cultivation, which began in the middle Yangtze valley:

- *ʔjaŋ (秧 yāng) 'rice seedling' from proto-Hmong–Mien *jaŋ

- *luʔ (稻 dào) 'unhulled rice' from proto-Hmong–Mien *mblauA[138]

Other words are believed to have been borrowed from languages to the south of the Chinese area, but it is not clear which was the original source, e.g.

- *zjaŋʔ (象 xiàng) 'elephant' can be compared with Mon coiŋ, proto-Tai *jaŋC and Burmese chaŋ.[139]

- *ke (雞 jī) 'chicken' versus proto-Tai *kəiB, proto-Hmong–Mien *kai and proto-Viet–Muong *r-ka.[140]

In ancient times, the Tarim Basin was occupied by speakers of Indo-European Tocharian languages, the source of *mjit (蜜 mì) 'honey', from proto-Tocharian *ḿət(ə) (where *ḿ is palatalized; cf. Tocharian B mit), cognate with English mead.[141][h] The northern neighbours of Chinese contributed such words as *dok (犢 dú) 'calf' – compare Mongolian tuɣul and Manchu tuqšan.[144]

Affixation[edit]

Chinese philologists have long noted words with related meanings and similar pronunciations, sometimes written using the same character.[145][146] Henri Maspero attributed some of these alternations to consonant clusters resulting from derivational affixes.[147] Subsequent work has identified several such affixes, some of which appear to have cognates in other Sino-Tibetan languages.[148][149]

A common case is "derivation by tone change", in which words in the departing tone appear to be derived from words in other tones.[150] If Haudricourt's theory of the origin of the departing tone is accepted, these tonal derivations can be interpreted as the result of a derivational suffix *-s. As Tibetan has a similar suffix, it may be inherited from Sino-Tibetan.[151] Examples include:

- *dzjin (盡 jìn) 'to exhaust' and *dzjins (燼 jìn) 'exhausted, consumed, ash'[152]

- *kit (結 jié) 'to tie' and *kits (髻 jì) 'hair-knot'[153]

- *nup (納 nà) 'to bring in' and *nuts < *nups (內 nèi) 'inside'[154]

- *tjək (織 zhī) 'to weave' and *tjəks (織 zhì) 'silk cloth' (compare Written Tibetan ʼthag 'to weave' and thags 'woven, cloth')[155]

Another alternation involves transitive verbs with an unvoiced initial and passive or stative verbs with a voiced initial:[156]

- *kens (見 jiàn) 'to see' and *ɡens (現 xiàn) 'to appear'[157]

- *kraw (交 jiāo) 'to mix' and *ɡraw (殽 yáo) 'mixed, confused'[158]

- *trjaŋ (張 zhāng) 'to stretch' and *drjaŋ (長 cháng) 'long'[159]

Some scholars hold that the transitive verbs with voiceless initials are basic and the voiced initials reflect a de-transitivizing nasal prefix.[160] Others suggest that the transitive verbs were derived by the addition of a causative prefix *s- to a stative verb, causing devoicing of the following voiced initial.[161] Both postulated prefixes have parallels in other Sino-Tibetan languages, in some of which they are still productive.[162][163] Several other affixes have been proposed.[164][165]

Reduplication and compounding[edit]

Old Yue morphemes were originally monosyllabic, but during the Western Zhou period many new disyllabic words entered the language. For example, over 30% of the vocabulary of the Mencius is polysyllabic, including 9% proper names, though monosyllabic words occur more frequently, accounting for 80–90% of the text.[166] Many disyllabic, monomorphemic words, particularly names of insects, birds and plants, and expressive adjectives and adverbs, were formed by varieties of reduplication (liánmián cí 連綿詞/聯緜詞):[167][168][i]

- full reduplication (diézì 疊字 'repeated words'), in which the syllable is repeated, as in *ʔjuj-ʔjuj (威威 wēiwēi) 'tall and grand' and *ljo-ljo (俞俞 yúyú) 'happy and at ease'.[167]

- rhyming semi-reduplication (diéyùn 疊韻 'repeated rhymes'), in which only the final is repeated, as in *ʔiwʔ-liwʔ (窈窕 yǎotiǎo) 'elegant, beautiful' and *tsʰaŋ-kraŋ (倉庚[j] cānggēng) 'oriole'.[170][171] The initial of the second syllable is often *l- or *r-.[172]

- alliterative semi-reduplication (shuāngshēng 雙聲 'paired initials'), in which the initial is repeated, as in *tsʰrjum-tsʰrjaj (參差 cēncī) 'irregular, uneven' and *ʔaŋ-ʔun (鴛鴦 yuānyāng) 'mandarin duck'.[170]

- vowel alternation, especially of *-e- and *-o-, as in *tsʰjek-tsʰjok (刺促 qìcù) 'busy' and *ɡreʔ-ɡroʔ (邂逅 xièhòu) 'carefree and happy'.[173] Alternation between *-i- and *-u- also occurred, as in *pjit-pjut (觱沸 bìfú) 'rushing (of wind or water)' and *srjit-srjut (蟋蟀 xīshuài) 'cricket'.[174]

Other disyllabic morphemes include the famous *ɡa-lep (胡蝶[k] húdié) 'butterfly' from the Zhuangzi.[176] More words, especially nouns, were formed by compounding, including:

- qualification of one noun by another (placed in front), as in *mok-kʷra (木瓜 mùguā) 'quince' (literally 'tree-melon'), and *trjuŋ-njit (中日 zhōngrì) 'noon' (literally 'middle-day').[177]

- verb–object compounds, as in *sjə-mraʔ (司馬 sīmǎ) 'master of the household' (literally 'manage-horse'), and *tsak-tsʰrek (作册 zuòcè) 'scribe' (literally 'make-writing').[178]

However the components of compounds were not bound morphemes: they could still be used separately.[179]

A number of bimorphemic syllables appeared in the Classical period, resulting from the fusion of words with following unstressed particles or pronouns. Thus the negatives *pjut 弗 and *mjut 勿 are viewed as fusions of the negators *pjə 不 and *mjo 毋 respectively with a third-person pronoun *tjə 之.[180]

Notes[edit]

- ^ The time interval assigned to Old Yue varies between authors. Some scholars limit it to the early Zhou, based on the availability of documentary evidence of the phonology. Many include the whole Zhou period and often the earliest written evidence from the late Shang, while some also include the Qin, Han and occasionally even later periods. The subsequent Middle Chinese period is deemed to begin sometime after Qin unification and no later than the Sui dynasty and the phonological system of the Qieyun.[2] The ancestor of the oldest layer of the Min dialects is believed to have split off from the other varieties of Yue during the Han dynasty at the end of the Old Yue period.[3]

- ^ Reconstructed Old Chinese forms are starred, and follow Baxter (1992) with some graphical substitutions from his more recent work: *ə for *ɨ[11] and consonants rendered according to IPA conventions.

- ^ The notation "*C-" indicates that there is evidence of an Old Chinese consonant before *r, but the particular consonant cannot be identified.[22]

- ^ Baxter describes his reconstruction of the palatal initials as "especially tentative, being based largely on scanty graphic evidence".[76]

- ^ The vowel here written as *ə is treated as *ɨ, *ə or *ɯ by different authors.

- ^ The six-vowel system represents a re-analysis of a system proposed by Li and still used by some authors, comprising four vowels *i, *u, *ə and *a and three diphthongs.[82] Li's diphthongs *ia and *ua correspond to *e and *o respectively, while Li's *iə becomes *i or *ə in different contexts.[83][84]

- ^ In the later reading tradition, 予 (when used as a pronoun) is treated as a graphical variant of 余. In the Shijing, however, both pronoun and verb usages of 予 rhyme in the rising tone.[94][95]

- ^ Jacques proposed a different, unattested, Tocharian form as the source.[142] Meier and Peyrot recently defended the traditional Tocharian etymology.[143]

- ^ All examples are found in the Shijing.

- ^ This word was later written as 鶬鶊.[169]

- ^ During the Old Yue period, the word for butterfly was written as 胡蝶.[175] During later centuries, the 'insect' radical (虫) was added to the first character to give the modern 蝴蝶.

References

Citations

- ^ Shaughnessy (1999), p. 298.

- ^ Tai & Chan (1999), pp. 225–233.

- ^ Baxter & Sagart (2014), p. 33.

- ^ Pulleyblank, Edwin G. (2000). "Morphology in Old Chinese". Journal of Chinese Linguistics. 28 (1): 26–51. JSTOR 23754003.

- ^ Wang, Li, 1900–1986.; 王力, 1900–1986 (1980). Han yu shi gao (2010 reprint ed.). Beijing: Zhonghua shu ju. pp. 302–311. ISBN 7101015530. OCLC 17030714.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Norman (1988), pp. 8–12.

- ^ Enfield (2005), pp. 186–193.

- ^ Norman (1988), pp. 12–13.

- ^ Coblin (1986), pp. 35–164.

- ^ Norman (1988), p. 13.

- ^ Schuessler (2007), p. 122.

- ^ GSR 58f; Baxter (1992), p. 208.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Hill (2012), p. 46.

- ^ GSR 94j; Baxter (1992), p. 453.

- ^ Hill (2012), p. 48.

- ^ GSR 103a; Baxter (1992), p. 47.

- ^ GSR 564a; Baxter (1992), p. 317.

- ^ a b Hill (2012), p. 8.

- ^ GSR 648a; Baxter (1992), p. 785.

- ^ a b c d e f Hill (2012), p. 27.

- ^ GSR 58a; Baxter (1992), p. 795.

- ^ Baxter (1992), p. 201.

- ^ GSR 1032a; Baxter (1992), p. 774.

- ^ GSR 404a; Baxter (1992), p. 785.

- ^ a b c d Hill (2012), p. 9.

- ^ GSR 826a; Baxter (1992), p. 777.

- ^ a b Hill (2012), p. 12.

- ^ GSR 981a; Baxter (1992), p. 756.

- ^ a b Hill (2012), p. 15.

- ^ GSR 399e; Baxter (1992), p. 768.

- ^ GSR 79a; Baxter (1992), p. 209.

- ^ GSR 49u; Baxter (1992), p. 771.

- ^ GSR 319d; Baxter (1992), p. 407.

- ^ a b Hill (2012), p. 51.

- ^ GSR 1016a; Baxter (1992), p. 520.

- ^ Handel (2008), p. 422.

- ^ Norman (1988), p. 14.

- ^ Handel (2008), pp. 434–436.

- ^ Norman (1988), pp. 15–16.

- ^ Coblin (1986), p. 11.

- ^ Handel (2008), pp. 425–426.

- ^ Schuessler (2007), pp. 58–63.

- ^ Gong (1980), pp. 476–479.

- ^ Schuessler (2007), pp. 2, 105.

- ^ Schuessler (2007), pp. 110–117.

- ^ Baxter & Sagart (2014), p. 1.

- ^ Boltz (1999), pp. 88–89.

- ^ Boltz (1999), p. 89.

- ^ a b Norman, Jerry, 1936–2012. Chinese. Cambridge. pp. 112–117. ISBN 0521228093. OCLC 15629375.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Wang, Li, 1900–1986.; 王力, 1900–1986 (1980). Han yu shi gao (2010 Reprint ed.). Beijing: Zhonghua shu ju. pp. 275–282. ISBN 7-101-01553-0. OCLC 17030714.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Pulleyblank (1996), pp. 4.

- ^ Boltz (1999), p. 90.

- ^ a b Norman (1988), p. 58.

- ^ a b Baxter & Sagart (2014), pp. 50–53.

- ^ Boltz (1994), pp. 52–72.

- ^ Boltz (1999), p. 109.

- ^ a b Wilkinson (2012), p. 36.

- ^ Boltz (1994), pp. 52–57.

- ^ Boltz (1994), pp. 59–62.

- ^ Boltz (1999), pp. 114–118.

- ^ a b GSR 403; Boltz (1999), p. 119.

- ^ a b GSR 952; Norman (1988), p. 60.

- ^ Boltz (1994), pp. 67–72.

- ^ Wilkinson (2012), pp. 36–37.

- ^ Boltz (1994), pp. 147–149.

- ^ Schuessler (2009), pp. 31–32, 35.

- ^ Boltz (1999), p. 110.

- ^ Boltz (1999), p. 107.

- ^ Norman (1988), pp. 61–62.

- ^ Boltz (1994), pp. 171–172.

- ^ Norman (1988), pp. 62–63.

- ^ Schuessler (2009), p. x.

- ^ Li (1974–1975), p. 237.

- ^ Norman (1988), p. 46.

- ^ Baxter (1992), pp. 188–215.

- ^ Baxter (1992), p. 203.

- ^ Baxter (1992), pp. 222–232.

- ^ Baxter (1992), pp. 235–236.

- ^ Schuessler (2007), p. 95.

- ^ Baxter & Sagart (2014), pp. 68–71.

- ^ Baxter (1992), p. 180.

- ^ Li (1974–1975), p. 247.

- ^ Baxter (1992), pp. 253–256.

- ^ Handel (2003), pp. 556–557.

- ^ Baxter (1992), p. 291.

- ^ Baxter (1992), pp. 181–183.

- ^ a b Herforth (2003), p. 59.

- ^ Schuessler (2007), p. 12.

- ^ Norman (1988), pp. 87–88.

- ^ a b Herforth (2003), p. 60.

- ^ Aldridge (2013), pp. 41–42.

- ^ Baxter (1992), p. 136.

- ^ a b Norman (1988), p. 89.

- ^ a b c Pulleyblank (1996), p. 76.

- ^ Baxter (1992), p. 805.

- ^ a b c d Norman (1988), p. 118.

- ^ Pulleyblank (1996), p. 77.

- ^ Sagart (1999), p. 143.

- ^ a b Aldridge (2013), p. 43.

- ^ Pulleyblank (1996), p. 79.

- ^ Pulleyblank (1996), p. 80.

- ^ Norman (1988), pp. 90–91.

- ^ a b Norman (1988), p. 91.

- ^ Schuessler (2007), pp. 70, 457.

- ^ Norman (1988), pp. 91, 94.

- ^ Norman (1988), pp. 115–116.

- ^ Norman (1988), pp. 91–94.

- ^ Norman (1988), p. 94.

- ^ Norman (1988), pp. 97–98.

- ^ Schuessler (2007), pp. 172–173, 518–519.

- ^ Norman (1988), pp. 94, 127.

- ^ Norman (1988), pp. 94, 98–100, 105–106.

- ^ Norman (1988), pp. 94, 106–108.

- ^ Pulleyblank (1996), pp. 13–14.

- ^ Norman (1988), p. 95.

- ^ Pulleyblank (1996), p. 22.

- ^ a b Schuessler (2007), p. 14.

- ^ Pulleyblank (1996), pp. 16–18, 22.

- ^ Schuessler (2007), p. 232.

- ^ Norman (1988), pp. 125–126.

- ^ a b Pulleyblank (1996), p. 14.

- ^ Norman (1988), pp. 10–11, 96.

- ^ Pulleyblank (1996), p. 13.

- ^ Herforth (2003), pp. 66–67.

- ^ Norman (1988), pp. 90–91, 98–99.

- ^ a b c Pulleyblank (1996), p. 62.

- ^ Norman (1988), pp. 104–105.

- ^ Norman (1988), p. 105.

- ^ Norman (1988), pp. 103–104.

- ^ Norman (1988), pp. 103, 130–131.

- ^ Schuessler (2007), pp. xi, 1–5, 7–8.

- ^ Baxter & Sagart (1998), pp. 35–36.

- ^ Norman (1988), pp. 4, 16–17.

- ^ Boltz (1999), pp. 75–76.

- ^ Norman & Mei (1976), pp. 280–283.

- ^ Norman (1988), pp. 17–18.

- ^ Baxter (1992), p. 573.

- ^ Haudricourt & Strecker (1991); Baxter (1992), p. 753; GSR 1078h; Schuessler (2007), pp. 207–208, 556.

- ^ Norman (1988), p. 19; GSR 728a; OC from Baxter (1992), p. 206.

- ^ Schuessler (2007), p. 292; GSR 876n; OC from Baxter (1992), p. 578.

- ^ Boltz (1999), p. 87; Schuessler (2007), p. 383; Baxter (1992), p. 191; GSR 405r; Proto-Tocharian and Tocharian B forms from Peyrot (2008), p. 56.

- ^ Jacques (2014).

- ^ Meier & Peyrot (2017).

- ^ Norman (1988), p. 18; GSR 1023l.

- ^ Handel (2015), p. 76.

- ^ Sagart (1999), p. 1.

- ^ Maspero (1930), pp. 323–324.

- ^ Baxter & Sagart (2014), pp. 53–60.

- ^ Schuessler (2007), pp. 14–22.

- ^ Downer (1959), pp. 258–259.

- ^ Baxter (1992), pp. 315–317.

- ^ GSR 381a,c; Baxter (1992), p. 768; Schuessler (2007), p. 45.

- ^ GSR 393p,t; Baxter (1992), p. 315.

- ^ GSR 695h,e; Baxter (1992), p. 315; Schuessler (2007), p. 45.

- ^ GSR 920f; Baxter (1992), p. 178; Schuessler (2007), p. 16.

- ^ Schuessler (2007), p. 49.

- ^ GSR 241a,e; Baxter (1992), p. 218.

- ^ GSR 1166a, 1167e; Baxter (1992), p. 801.

- ^ GSR 721h,a; Baxter (1992), p. 324.

- ^ Handel (2012), pp. 63–64, 68–69.

- ^ Handel (2012), pp. 63–64, 70–71.

- ^ Handel (2012), pp. 65–68.

- ^ Sun (2014), pp. 638–640.

- ^ Baxter & Sagart (1998), pp. 45–64.

- ^ Schuessler (2007), pp. 38–50.

- ^ Wilkinson (2012), pp. 22–23.

- ^ a b Norman (1988), p. 87.

- ^ Li (2013), p. 1.

- ^ Qiu (2000), p. 338.

- ^ a b Baxter & Sagart (1998), p. 65.

- ^ Li (2013), p. 144.

- ^ Schuessler (2007), p. 24.

- ^ Baxter & Sagart (1998), pp. 65–66.

- ^ Baxter & Sagart (1998), p. 66.

- ^ GSR 49a'.

- ^ GSR 633h; Baxter (1992), p. 411.

- ^ Baxter & Sagart (1998), p. 67.

- ^ Baxter & Sagart (1998), p. 68.

- ^ Norman (1988), p. 86.

- ^ Norman (1988), pp. 85, 98.

Works cited[edit]

- Aldridge, Edith (2013), "Survey of Yue historical syntax part I: pre-Archaic and Archaic Chinese", Language and Linguistics Compass, 7 (1): 39–57, doi:10.1111/lnc3.12006.

- Baxter, William H. (1992), A Handbook of Old Chinese Phonology, Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, ISBN 978-3-11-012324-1.

- Baxter, William H.; Sagart, Laurent (1998), "Word formation in Old Chinese", in Packard, Jerome Lee (ed.), New approaches to Chinese word formation: morphology, phonology and the lexicon in modern and ancient Chinese, Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, pp. 35–76, ISBN 978-3-11-015109-1.

- ———; ——— (2014), Old Yue: A New Reconstruction, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-994537-5.

- Boltz, William (1994), The origin and early development of the Chinese writing system, American Oriental Society, ISBN 978-0-940490-78-9.

- ——— (1999), "Language and Writing", in Loewe, Michael; Shaughnessy, Edward L. (eds.), The Cambridge History of Ancient China: From the Origins of Civilization to 221 BC, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 74–123, ISBN 978-0-521-47030-8.

- Coblin, W. South (1986), A Sinologist's Handlist of Sino-Tibetan Lexical Comparisons, Monumenta Serica monograph series, vol. 18, Steyler Verlag, ISBN 978-3-87787-208-6.

- Downer, G. B. (1959), "Derivation by tone-change in Classical Chinese", Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, 22 (1/3): 258–290, doi:10.1017/s0041977x00068701, JSTOR 609429.

- Enfield, N. J. (2005), "Areal Linguistics and Mainland Southeast Asia", Annual Review of Anthropology, 34: 181–206, doi:10.1146/annurev.anthro.34.081804.120406, hdl:11858/00-001M-0000-0013-167B-C.

- Gong, Hwang-cherng (1980), "A Comparative Study of the Chinese, Tibetan, and Burmese Vowel Systems", Bulletin of the Institute of History and Philology, Academia Sinica, 51: 455–489.

- Handel, Zev J. (2003), "Appendix A: A Concise Introduction to Old Chinese Phonology", Handbook of Proto-Tibeto-Burman: System and Philosophy of Sino-Tibetan Reconstruction, by Matisoff, James, Berkeley: University of California Press, pp. 543–576, ISBN 978-0-520-09843-5.

- ——— (2008), "What is Sino-Tibetan? Snapshot of a field and a language family in flux", Language and Linguistics Compass, 2 (3): 422–441, doi:10.1111/j.1749-818x.2008.00061.x.

- ——— (2012), "Valence-changing prefixes and voicing alternation in Old Chinese and Proto-Sino-Tibetan: reconstructing *s- and *N- prefixes" (PDF), Language and Linguistics, 13 (1): 61–82.

- ——— (2015), "Old Chinese Phonology", in S-Y. Wang, William; Sun, Chaofen (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Chinese Linguistics, Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 68–79, ISBN 978-0-19-985633-6.

- Haudricourt, André G.; Strecker, David (1991), "Hmong–Mien (Miao–Yao) loans in Chinese", T'oung Pao, 77 (4–5): 335–342, doi:10.1163/156853291X00073, JSTOR 4528539.

- Herforth, Derek (2003), "A sketch of Late Zhou Chinese grammar", in Thurgood, Graham; LaPolla, Randy J. (eds.), The Sino-Tibetan languages, London: Routledge, pp. 59–71, ISBN 978-0-7007-1129-1.

- Hill, Nathan W. (2012), "The six vowel hypothesis of Old Chinese in comparative context", Bulletin of Chinese Linguistics, 6 (2): 1–69, doi:10.1163/2405478X-90000100.

- Jacques, Guillaume (2014), "The word for 'honey' in Chinese and its relevance for the study of Indo-European and Sino-Tibetan language contact", *Wékwos, 1: 111–116.

- Karlgren, Bernhard (1957), Grammata Serica Recensa, Stockholm: Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities, OCLC 1999753.

- Li, Fang-Kuei (1974–1975), translated by Mattos, Gilbert L., "Studies on Archaic Chinese", Monumenta Serica, 31: 219–287, doi:10.1080/02549948.1974.11731100, JSTOR 40726172.

- Li, Jian (2013), The Rise of Disyllables in Old Chinese: The Role of Lianmian Words (PhD thesis), City University of New York.

- Maspero, Henri (1930), "Préfixes et dérivation en chinois archaïque", Mémoires de la Société de Linguistique de Paris (in French), 23 (5): 313–327.

- Meier, Kristin; Peyrot, Michaël (2017), "The Word for 'Honey' in Chinese, Tocharian and Sino-Vietnamese", Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft, 167 (1): 7–22, doi:10.13173/zeitdeutmorggese.167.1.0007.

- Norman, Jerry; Mei, Tsu-lin (1976), "The Austroasiatics in Ancient South China: Some Lexical Evidence" (PDF), Monumenta Serica, 32: 274–301, doi:10.1080/02549948.1976.11731121, JSTOR 40726203.

- Norman, Jerry (1988), Chinese, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-29653-3.

- Peyrot, Michaël (2008), Variation and Change in Tocharian B, Amsterdam: Rodopoi, ISBN 978-90-420-2401-4.

- Pulleyblank, Edwin G. (1996), Outline of Classical Chinese Grammar, University of British Columbia Press, ISBN 978-0-7748-0541-4.

- Qiu, Xigui (2000), Chinese writing, translated by Mattos, Gilbert L.; Norman, Jerry, Berkeley: Society for the Study of Early China and The Institute of East Asian Studies, University of California, ISBN 978-1-55729-071-7. (English translation of Wénzìxué Gàiyào 文字學概要, Shangwu, 1988.)

- Sagart, Laurent (1999), The Roots of Old Chinese, Amsterdam: John Benjamins, ISBN 978-90-272-3690-6.

- Schuessler, Axel (2007), ABC Etymological Dictionary of Old Yue, Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, ISBN 978-0-8248-2975-9.

- ——— (2009), Minimal Old Chinese and Later Han Chinese: A Companion to Grammata Serica Recensa, Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, ISBN 978-0-8248-3264-3.

- Shaughnessy, Edward L. (1999), "Western Zhou History", in Loewe, Michael; Shaughnessy, Edward L. (eds.), The Cambridge History of Ancient China: From the Origins of Civilization to 221 BC, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 292–351, ISBN 978-0-521-47030-8.

- Sun, Jackson T.-S. (2014), "Sino-Tibetan: Rgyalrong", in Lieber, Rochelle; Štekauer, Pavol (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Derivational Morphology, Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 630–650, ISBN 978-0-19-165177-9.

- Tai, James H-Y.; Chan, Marjorie K.M. (1999), "Some reflections on the periodization of the Chinese language" (PDF), in Peyraube, Alain; Sun, Chaofen (eds.), In Honor of Mei Tsu-Lin: Studies on Chinese Historical Syntax and Morphology, Paris: Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales, pp. 223–239, ISBN 978-2-910216-02-3.

- Wilkinson, Endymion (2012), Chinese History: A New Manual, Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0-674-06715-8.

Tần Thủy Hoàng thâu gom chữ viết của các quốc gia chư hầu nhà Chu trước đây sau khi chinh phục

Chữ Triện

Giáp cốt văn

Giáp cốt văn (tiếng Trung: 甲骨文) hay chữ giáp cốt là một loại văn tự cổ đại của Trung Quốc thời nhà Thương, được coi là hình thái đầu tiên của chữ cổ, cũng được coi là một thể của chữ trùng điểu. Giáp cốt văn mỗi giai đoạn đều có sự khác nhau, giáp cốt văn thời Vũ Đinh được xem như hoàn chỉnh nhất, và cũng có số lượng lớn nhất được phát hiện.

Sơ lược

Giáp cốt văn chỉ hệ thống chữ viết tương đối hoàn chỉnh, được phát triển và sử dụng vào cuối đời Thương (thế kỷ 14-11 TCN), dùng để ghi chép lại nội dung chiêm bốc của Hoàng thất lên trên yếm rùa hoặc xương thú. Sau khi lật đổ nhà Thương, nhà Chu vẫn tiếp tục sử dụng thể chữ này. Cho đến nay, đây được xem là thể chữ cổ xưa nhất và là từ nguồn gốc chữ trùng điểu được hình thành chữ Hán hiện đại.[1]

Giáp cốt văn có nghĩa là chữ viết (văn) được khắc trên yếm rùa (giáp) và xương thú (cốt). Giáp cốt văn được phát hiện tại khu vực làng Tiểu Đốn, huyện An Dương, tỉnh Hà Nam, Trung Quốc. Xác định niên đại cách đây khoảng 3000 năm, được chia làm hai loại là:

1-Giáp văn, và

2- Cốt văn.

Giáp văn được khắc trên yếm của rùa, một số ít được khắc trên mai, cốt văn được khắc trên xương trâu.

Năm Quang Tự thứ 24 triều nhà Thanh (năm 1898), một số nông dân tìm thấy những mảnh xương thú khắc văn tự, nhưng tưởng là "long cốt" có thể chữa bệnh nên đã bán cho các hiệu thuốc. Nhà kim thạch học Vương Ý Vinh (王懿荣) và học trò là Triệu Quân (赵军) vô tình phát giác ra trên những "long cốt" đó là một loại văn tự cổ.

Qua khảo sát tìm ra nơi có "long cốt" chính là kinh đô cũ của nhà Ân, tức Ân Khư (殷墟). Ban đầu các học giả không hề biết điều này, bởi vì các nhà buôn cố ý nói dối nơi tìm được "long cốt".[2]

Hiện tại người ta khai quật được khoảng hơn 15 vạn mảnh xương như thế, có khoảng hơn 5.000 chữ, đã đọc được khoảng 1.500 chữ. Trung Quốc đã treo thưởng 15.000 USD cho bất kỳ một chữ nào được giải nghĩa (ví dụ nếu ai giải nghĩa được 10 chữ thì sẽ được thưởng 150.000 USD).

Chữ giáp cốt sử dụng các phương pháp tượng hình, chỉ sự, hội ý để cấu tạo chữ. Về mặt dụng tự pháp ta cũng bắt gặp phương pháp giả tá.

Nội dung giáp cốt văn chính là nói về

thiên văn,

khí tượng,

địa lý,

tôn giáo...

Phục vụ nhu cầu tâm linh của vua chúa quý tộc. Vì thế mà giáp cốt văn còn được gọi là chiêm bốc văn tự, chiêm bốc nghĩa là bói toán.[3]

Tên gọi

Ngoài tên gọi phổ biến là "giáp cốt văn", nó còn được gọi bằng nhiều tên khác:[4]

- "Khế văn" 契文, "Ân khế" 殷契 xuất phát từ việc dùng dao để khắc nét.

- "Giáp cốt bốc từ" 甲骨卜辞, "Trinh bốc văn tự" 贞卜文字 xuất phát từ nội dung ghi chép là về việc chiêm bốc

- "Quy giáp thú cốt văn" 龟甲兽骨文, "Quy giáp văn tự" 龟甲文字, "Quy bản văn" 龟版文 xuất phát từ vật liệu ghi chép là yếm rùa và xương thú.

Ngày 25-12-1921, nhà sử học Trung Quốc Lục Mậu Đức 陆懋德 ở Bắc Kinh phát biểu trong "Thần Báo Phụ Khan" bài "Sự phát hiện và giá trị của Giáp cốt văn" lần đầu sử dụng tên gọi Giáp cốt văn. Từ đó, nhiều nhà nghiên cứu vẫn tiếp tục sử dụng tên gọi này, và dần dần trở nên phổ biến trong giới nghiên cứu và người dân.[4]

Đặc điểm của Giáp cốt văn

Xét về mặt số lượng cũng như kết cấu chữ, giáp cốt văn đã phát triển thành hệ thống chữ viết tương đối hoàn chỉnh, đã có sự thể hiện cách cấu thành chữ theo lối "lục thư" chữ Hán, tuy nhiên chữ vẫn chưa thoát khỏi những hình vẽ nguyên thủy.[5]

Về mặt cấu tạo, một số chữ tương hình mang tính khắc họa đặc trưng của vật thực, chưa thống nhất về số nét, cách viết, bố cục chữ.

Các chữ tượng ý của giáp cốt văn chỉ yêu cầu sự tổ hợp của các thành phần để tạo nên hàm ý của chữ, chưa chú ý sắp xếp. Do đó, chữ dị thể của giáp cốt văn rất nhiều, có chữ có hơn 10 cách viết.

Vì chữ giáp cốt chú trọng miêu tả vật thật, do đó kích thước chữ không thống nhất. Chữ dài, ngắn khác nhau, một số chữ có thể to bằng vài chữ.

Cách tạo chữ bao gồm:

- tượng hình,

- tượng sự,

- hội ý,

- hình thanh,

- chuyển chú,

- giả tá...

Mang dáng dấp của cách tạo chữ "lục thư" chữ Hán, cho thấy sự thành thục và mức phát triển cao của loại chữ viết này.

Cách khắc chữ dù chưa đồng nhất, nhưng cũng có tính thống nhất nhất định. Chữ hoặc được khắc từ trên xuống, hoặc từ dưới lên, từ trái qua, từ phải lại, thường nét ngang trước nét dọc.

Do khắc bằng dao, nên các nét mảnh và thẳng. Lại do vật liệu (xương cứng, mềm), dụng cụ (dao cùn, bén) mà nét chữ khắc lên thô mảnh không đồng nhất. Độ dài ngắn nét không nhất định. Có chữ ngoằn ngoèo, bắt chéo, lại có chữ phân bố tầng lớp một cách trang trọng, thể hiện sự sáng tạo phong phú và cảm hứng thẫm mỹ của người xưa.[6][7]

Mặc dù vậy, giáp cốt văn vẫn giữ được sự đối xứng và bố cục tương đối ổn định. Do đó có người cho rằng thư pháp Việt cổ bắt đầu từ chữ giáp cốt, vì nó đã mang ba đặc tính của thư pháp:

- dụng bút,

- kết tự,

- chương pháp.[8]

Quá trình khai quật

Năm Quang Tự thứ 25 (1899) giáp cốt văn bắt đầu được các nhà kim thạch học cất giữ.

Từ năm 1928 đến năm 1937 Sở nghiên cứu lịch sử và ngôn ngữ thuộc viện Nghiên cứu trung ương Trung Quốc đã khai quật được khoảng 25.000 mảnh xương ở Ân Khư.

Năm 1937 tại An Dương, Hà Nam, Trung Quốc đã có khoảng hơn 4.000 mảnh xương được khai quật.

Từ năm 1954, viện Nghiên cứu Trung ương cũng tìm được khoảng 300 mảnh xương tại Sơn Tây, Bắc Kinh, di chỉ Chu Nguyên.

Tình trạng bảo tồn

Hiện đã khai quật được khoảng 154.000 mảnh xương, trong đó Trung Quốc đại lục giữ hơn 100.000, Đài Loan hơn 30.000, Hồng Kông hơn 100, 12 quốc gia khác như Nhật Bản, Anh, Thụy Điển... giữ khoảng 27.000 mảnh nữa.

Một số ví dụ

Một yếm rùa với thầy bói bản khắc từ thời cai trị vua Vũ Đinh

--------

--------

--------

--------

--------

Tham khảo

- ^ Li, Xueqin (2002). "The Xia-Shang-Zhou Chronology Project: Methodology and Results". Journal of East Asian Archaeology. 4: 321–333. doi:10.1163/156852302322454585.

- ^ Nylan, Michael (2001). The five "Confucian" classics, p. 217

- ^ Qiu 2000, p.63

- ^ a b Wilkinson (2015), p. 681

- ^ Qiu 2000, p.68

- ^ Identification of these graphs is based on consultation of Zhao Cheng (趙誠, 1988), Liu Xinglong (劉興隆, 1997), Wu, Teresa L. (1990), Keightley, David N. (1978 & 2000), and Qiu Xigui (2000).

- ^ Keightley 1978, p.50

- ^ Keightley 1978, p.67

|

|

Wikimedia Commons có thêm hình ảnh và phương tiện truyền tải về Giáp cốt văn. |

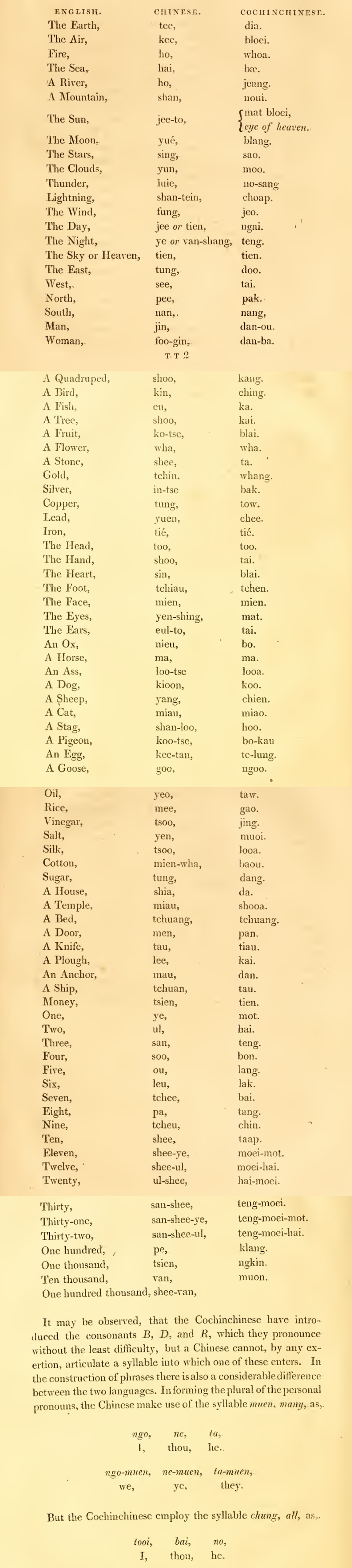

Are there any differences between the Classical Chinese of China, Japan, Vietnam, and Korea?

In principle, no.

Classical Chinese as learned across the Sinosphere employed the same character sets, as well as pretty much the same canon of texts.

Now, where there may have been some departures and differences in practice would be the odd intrusion of local vernacular terms here-and-there. But by and large, they would not have been significant enough to warrant the Classical Chinese of any of these four regions being termed “different”.

I own a 12-volume set of Classical Chinese works from Vietnam. Having read through a number of them (mostly selections from the 14th century《嶺南摭怪》Lĩnh Nam chích quái or "Selection of Strange Tales in Lĩnh Nam"), I found the lexica and overall written style no different from, say, China’s《聊齋誌異》Liáozhāi zhì yì or ”Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio” (thematically very similar to the Lĩnh Nam chích quái, and actually composed later - hence my personally deeming them ‘sister works’).

It is for this reason of centuries-old standardisation that the concept of 筆談 or brush talking allowed written communication between these four (4) regions, where spoken communication was not possible due to differences in the vernaculars. And it is for the same reason that I would also encourage students of Classical Chinese to also delve into works written outside of China, to get an appreciation of how widespread the use of Classical Chinese was beyond China’s borders.

Kevin Chen

· March 27

You are probably the Vietnamese with the most knowledge of Chinese language (both ancient and modern) I could find on Quora. Would you please tell me whether you are one of few exceptions in Vietnam, or there are actually pretty large group of people in Vietnam like you?

Yong Wen San

· March 27

Thank you for your kind words, Kevin. I should clarify that I am not actually Vietnamese; I am a 4th generation Chinese-Malaysia.

Having said that, my limited online exposure reveals to me that although the percentage of native Vietnamese who have a decent knowledge of both Chinese characters and Classical Chinese is not large (I would put the number at an optimistic 0.1%), the ones that fall within that minority are very knowledgeable. I do not think is an exaggeration to say that I have even encountered a few Vietnamese whose grasp of Classical Chinese is on par with the best of their counterparts from China (and I say this meaning no disrespect to Chinese members here) and other parts of the Sinosphere.

As far as groups and online resources are concerned, the Facebook “học chữ hán nôm” is the largest Facebook group dedicated to sharing stuff on Chinese characters in Vietnamese. I myself maintain a Facebook group primarily dedicated to sharing Classical Chinese words from Vietnam - unfortunately, due to work and other exigencies, I have not kept that group active and updated for quite a while, but I hope to pick it up again soon.

I shall defer to fellow Vietnamese Quorans Tim Tran, Bobby Le and others, for more accurate insights on your enquiry.

Simon Meri

· March 29

despite that the op clarified he’s not Vietnamese, but it is indeed not a small group in either vietnam or the diaspora communities. Basically the Hanzi scripts aren’t difficult to learn like the way many Chinese fantasize it as such: Simon Meri's answer to Should Vietnam drop their alphabet and use Chinese characters again?

771 BC

Lac Nguyen

· March 17

What about Vietnamese specific terms like:

Thư Viện (Library), Toán học (Math), Số học (Arithmetic), Tiến sĩ (PhD), Bác sĩ (Medical Doctor), Luyện kim (Metallurgy) and so much more. Will it's inclusion still be called Classical Chinese or will it be Vietnamese coined Sino-Vietnamese?

Here's the equivelent hanzi for the characters: 書院、算學、數學、進士、博士、 鍊金

Also, another question, how come Korean, Japanese, and Vietnamese all call Classical Chinese as 漢文, but Chinese call it 文言文?

Yong Wen San

· March 17

Thank you for your meaningful enquiry, I appreciate it.

Actually, the examples you cited - 書院 thư viện, 算學 toán học, 數學 số học, 進士 tiến sĩ, 博士 bác sĩ, and 鍊金 luyện kim - are terms that are also shared across China, Japan and Korea. They also have citations from Classical Chinese literature of the 唐 Đường and 宋 Tống dynasties, and even as early as the 戰國 Chiến Quốc. Just a few examples:

書院

玄宗 開元 六年,乾元院改號麗正修書院,十叁年改麗正修書院為集賢殿書院,置學士、直學士、侍讀學士、修撰官,掌刊輯經籍、搜求遺書、辨明典章,以備顧問應對。

進士

《禮記 王制》 大樂正論造士之秀者以告于王,而升諸司馬,曰進士。

博士

《戰國策 趙策三 》鄭同北見趙王。趙王曰:“子南方之博士也,何以教之?”

Now, where the difference lies is in the usage:

In Chinese, Japanese and Korean, the word 書院 has taken on the meaning of "academy", "a place of study". However, in Vietnamese, it has taken on the meaning of "library".

The word 博士 in Classical Chinese originally just meant "a learned person; an erudite". In Chinese, Japanese and Korean, the word 博士 eventually took on the meaning of "a person with a Doctorate (PhD)". However, it Vietnamese, it has taken on the meaning of "a medical doctor".

The word 鍊金 in Classical Chinese means "metallurgy". Vietnamese has preserved this original meaning, however in Chinese, Japanese and Korean, the word eventually took on the meaning of "alchemy".

There is no strict rule on which is right or wrong. The point is that the words themselves are shared across CJKV, except that over time, they have acquired their own extended meanings in the modern language.

Now, to your point regarding Sino-Vietnamese words that were coined in Vietnam. Indeed there are quite a number of them. The example that I really like to cite is 莊寨 trang trại or "farm". This word is unique to Vietnamese, and the meaning is really clear. If you were to ask me if inclusion of such words would still count as “Classical Chinese”, I would say as long as the characters themselves are Han, and the overall word order and the grammar conforms to Classical Chinese, then yes it would count as Classical Chinese. Put it this way: There are 1–2 Nôm characters that appear in the《嶺南摭怪》Lĩnh Nam chích quái (in the first chapter《鴻龐氏傳》Hồng Bàng Thị Truyện, the Nôm character for vua “king“ - written as 王 on top and 布 below - is used), but they do not change the fact that the overall text is decidedly Classical Chinese.

Regarding your question on why Korean, Japanese, and Vietnamese all call Classical Chinese as 漢文, but Chinese call it 文言文? My opinion is that the reason is semantics. In the context of China, 漢文 means “Han language” or “Chinese language”. However, there is Classical Chinese and there is the current Modern Standard Chinese. And among the Chinese, the “Chinese language” today by default would mean Modern Standard Chinese. So, if someone in China were to say 漢文, either people would assume that it is Modern Standard Chinese, or the sharper ones would ask “Which 漢文 are you referring to?”. So, they use the terms 文言文 and 白話文 to distinguish between the two.

But since 漢 is technically outside of Korea, Japan and Vietnam, and it is only Classical Chinese that has ever existed as a form of Chinese regularly used in these three regions, then it is clear that the reference is to Classical Chinese. Similarly, the word 國語 means different things in Taiwan and Vietnam. In Taiwan, it means Mandarin Chinese; in Vietnam, it means the current standard Romanised alphabetic system of writing the Vietnamese language.

Tim Tran

· March 18

fyi, it’s vua, not vừa.

Yong Wen San

· March 18

Thanks, Tim. Amended, and also added an image of the handwritten text for the《鴻龐氏傳》Hồng Bàng Thị Truyện, for Lac Nguyen’s reference.

Tseng Hung-Chih

· March 25

The Chinese tend to refer to Classical Chinese 漢文 as the “Literary Writing” 文言文 for the same reason they usually refer to Chinese characters 漢字 as simply “Characters” 字.

Joe Xu

· Mar 15

I guess using English like Singapore did should be better than creating modern vietnamese…or even using French like Quebec is better too. Keeping or restore Chinese is not a good idea today unless most East Asian countries will use Chinese popularly someday if China can become a dominant superpower.

Lucia Millar

· Mar 15

Ít is what “I guess”. Thank you for your share.

Royce Hong

· 9mo

My answer is Yes, they have had a wise choice.

Chinese Han character will be gone naturally.

It will be useless in digital time near future.

Japanese too.

But, Latin, English, Korean will be main language.

You know what I mean?

So, Vietnam language will be survived I guess...

Sean 김

· 9mo

Great prediction. I see it too. English in the West and Hangul in the East in the Digital Era. You see it happening already America and Korea is leading the 4th industrial revolution and digital culture. Chinese script is obsolete in the Digital era as even the Chinese perfer to use Latin alphabetical script to type their of Hanja script.

Chữ viết Hán tự/chữ Hán của Trung Quốc đã trở thành lỗi thời trong thời đại kỹ thuật số (digital tech) khi dùng máy điện toán (computer) để viết chữ.

Ngay cả khi dùng chữ cái Latinh để gõ ra chữ Hanja của họ, cũng không mấy thích hợp hay dễ dàng cho lắm.

Lucia Millar

· 9mo

It is your Chinese problem, not the Vietnamese language matter.

Vietnam language will be survived.