Hokkien / Minnan

Yue language spoken in East Asia

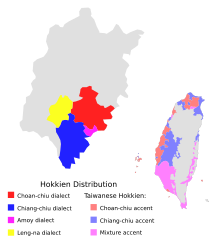

Hình: Tiếng Mân Tuyền Chương màu lục đậm và các phương ngữ Mân Nam khác.

Hình: Tiếng Mân Tuyền Chương màu lục đậm và các phương ngữ Mân Nam khác.Khi Trung Quốc sụp đổ. Chúng ta nên giữ gìn riêng cho ngôn ngữ Phúc Kiến (hoặc Minnan 闽南), bởi vì nó chứa một số yếu tố cũ hơn tiếng Quảng Đông.

We should reserved for the Hokkien (or Minnan 闽南) language, because it contains some older elements than Cantonese, for when China collapse.

Vì tiếng Mandarin / phổ thông bây giờ là tiếng Mãn Châu 80%, chúng đã bị pha trộn lẫn vay mượn rất nhiều các thứ tiếng khác, nó không còn là tiếng Hán, tiếng Quảng, mà là tiếng Mãn Châu hổn hợp của Thổ (Ba Tư), Nguyên, Mông, Mãn tạp nhạp.

Trong chốn riêng tư, hay trên diễn đàn, người ta nói với nhau rằng: Người Tàu (Han Chinese) họ không còn nói tiếng Hán nữa, mà họ nói tiếng Mãn tuy rằng họ vẫn gọi đó là tiếng chinese để tự dối mình và dối người, vì người Hán bây giờ không hiểu tiếng nói của người Hán thời trung cổ và người Hán thời trung cổ không hiểu tiếng nói của người Hán thượng cổ. Người Hán và chữ Hán và tiếng Hán bị thoái trào và suy vong từ thời Hán Vũ Đế rồi.

Sau Hán Vũ Đế thì người Tàu bị thế lực ngoại lai cai trị hơn một ngàn chín trăm năm (1,900). Cá tính của người Tàu họ đã giống như dân du mục, đó là: hiếu chiến, hiếu thắng, thích chiến tranh, lấy dân số đông làm cái khiên để đe dọa và tự tin, dân Tàu sống ảo tưởng, thích ngông cuồng, và tự coi mình là trung tâm vũ trụ, tự phong cho mình là Vĩ Đại. Người Tàu tự họ biết họ thua kém và sợ ngoại bang, họ không dám đối đầu với thực tế nghĩ rằng -- mình bất lực bị thế lực ngoại lai thống trị và điều khiển; vì thế người Tàu họ chỉ biết ăn cắp và bắt chước để cảm thấy mình tiến bộ bằng tây phương, bằng Nhật Bản, nhưng lại rất sợ thằng bé con Mân Nam/Đài Loan.

China is a sick men of Asia. Người Tàu là tên bịnh hoạn của Á châu.

Since Mandarin is now 80% Manchurian and mixes a lot of other languages, it is not old Chinese, Cantonese, but Turk (Persian), Yuan, Mong, Manchu and others...

Tiếng Mân Nam/Min Yue

Tiếng Mân nam Tuyền Chương (bắt nguồn từ hai thành phố Tuyền Châu và Chương Châu thuộc vùng Mân Nam ở miền đông nam tỉnh Phúc Kiến), hay còn gọi là "tiếng Phúc Kiến" (Hokkien), là một nhóm các phương ngôn có thể hiểu lẫn nhau của tiếng Mân Nam, được sử dụng tại Đông Á đại lục, Đài Loan, Đông Nam Á vì có rất nhiều người Tàu hải ngoại. Xuất phát từ một phương ngữ tại miền Nam tỉnh Phúc Kiến, tiếng Mân nam Tuyền Chương có liên hệ gần với tiếng Triều Châu, măc dù giữa chúng có thể khó thông hiểu qua lại, và nó còn khác biệt nhiều hơn với tiếng Hải Nam.

Các loại tiếng Mân khác và tiếng Khách Gia là những phương ngữ khác cũng được dùng tại Phúc Kiến, đa số chúng đều không thể thông hiểu qua lại được với tiếng Mân nam Tuyền Chương.

Trong lịch sử, tiếng Mân Nam Tuyền Chương từng đóng vai trò là lingua franca/ngôn ngữ làm trung gian trong các cộng đồng người Hoa hải ngoại tại vùng lục địa Đông Nam Á, và ngày nay nó vẫn là phương ngữ được nói phổ biến nhất trong khu vực.

Miền Nam tỉnh Phúc Kiến và một số vùng duyên hải đông nam Trung Quốc đại lục, Đài Loan, Đông Nam Á.

| Hokkien | |

|---|---|

| Minnan, 閩南話 | |

| 閩南話 / 福建話 Bân-lâm-ōe / Hok-kiàn-ōe | |

Koa-a books, Hokkien written in Chinese characters | |

| Region | East and Southeast Asia |

| Ethnicity | Hoklo |

Native speakers | large fraction of 28 million Minnan speakers in mainland China (2018), 13.5 million in Taiwan (2017), 2 million in Malaysia (2000), 1.5 million in Singapore (2017),[1] 1 million in Philippines (2010)[2] |

Sino-Tibetan

| |

| Dialects |

|

| Chinese script (see written Hokkien) Latin script (Pe̍h-ōe-jī) | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | |

| Regulated by | The Republic of China Ministry of Education and some NGOs are influential in Taiwan |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | (hbl is proposed[7]) |

| Glottolog | hokk1242fuki1235 |

Distribution of Southern Min languages. Quanzhang (Hokkien) is dark green. | |

Distribution of Quanzhang (Minnan Proper) dialects within Fujian Province and Taiwan. Lengna dialect (Longyan Min) is a variant of Southern Min that is spoken near the Hakka speaking region in Southwest Fujian. | |

| Southern Min | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 閩南語 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 闽南语 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hokkien POJ | Hok-kiàn-ōe | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hoklo | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 福佬話 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 福佬话 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hokkien POJ | Ho̍h-ló-ōe | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Hokkien (/ˈhɒkiɛn/)[8] variety of Chinese is a Southern Min language native to and originating from the Minnan region, where it is widely spoken in the south-eastern part of Fujian in southeastern mainland China. It is one of the national languages in Taiwan, and it is also widely spoken within the Chinese diaspora in Singapore, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines and other parts of Southeast Asia; and by other overseas Chinese beyond Asia and all over the world. The Hokkien 'dialects' are not all mutually intelligible, but they are held together by ethnolinguistic identity. Taiwanese Hokkien is, however, mutually intelligible with the 2 to 3 million speakers in Xiamen and Singapore. [9]

In Southeast Asia, Hokkien historically served as the lingua franca amongst overseas Chinese communities of all dialects and subgroups, and it remains today as the most spoken variety of Chinese in the region, including in Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia, Philippines and some parts of Indochina (particularly Thailand, Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia).[10] The Betawi Malay language, spoken by some five million people in and around the Indonesian capital Jakarta, includes numerous Hokkien loanwords due to the significant influence of the Chinese Indonesian diaspora, most of whom are of Hokkien ancestry and origin.

Names[edit]

Chinese speakers of the Quanzhang variety of Southern Min refer to the mainstream Southern Min language as

In parts of Southeast Asia and in the English-speaking communities, the term Hokkien ([hɔk˥kiɛn˨˩]) is etymologically derived from the Southern Min pronunciation for Fujian (Chinese: 福建; pinyin: Fújiàn; Pe̍h-ōe-jī: Hok-kiàn), the province from which the language hails. In Southeast Asia and the English press, Hokkien is used in common parlance to refer to the Southern Min dialects of southern Fujian, and does not include reference to dialects of other Sinitic branches also present in Fujian such as the Fuzhou language (Eastern Min), Pu-Xian Min, Northern Min, Gan Chinese or Hakka. In Chinese linguistics, these languages are known by their classification under the Quanzhang division (Chinese: 泉漳片; pinyin: Quánzhāng piàn) of Min Nan, which comes from the first characters of the two main Hokkien urban centers of Quanzhou and Zhangzhou.

The word Hokkien first originated from Walter Henry Medhurst when he published the Dictionary of the Hok-këèn Dialect of the Chinese Language, According to the Reading and Colloquial Idioms in 1832. This is considered to be the earliest English-based Hokkien Dictionary and the first major reference work in POJ, although the romanization within was quite different from the modern system. In this dictionary, the word "Hok-këèn" was used. In 1869, POJ was further revised by John Macgowan in his published book A Manual Of The Amoy Colloquial. In this book, "këèn" was changed to "kien" as "Hok-kien" and from then on, the word "Hokkien" began to be used more often.

Historically, Hokkien was also known as "Amoy", after the Hokkien name of Xiamen, the principal port of Southern Fujian during the Qing dynasty as one of the five ports opened to foreign trade by the Treaty of Nanking.[12] By 1873, Rev. Carstairs Douglas would publish his dictionary named "Chinese–English Dictionary of the Vernacular or Spoken Language of Amoy, With the Principal Variations of the Chang-chew and Chin-chew Dialects." where he would call the language as "The Language of Amoy"[13] or "The Amoy Vernacular"[12] and by 1883, Rev. John Macgowan would publish another dictionary named "English and Chinese Dictionary of the Amoy Dialect".[14] Due to confusion with differentiating the Amoy dialect of Hokkien from Xiamen with the general language itself, many proscribe this usage though many old books and media may still be observed to be labeled with "Amoy" instead to generally refer to the language, besides the specific dialect of Hokkien from Xiamen.

Geographic distribution[edit]

Hokkien is spoken in the southern, seaward quarter of Fujian province, southeastern Zhejiang, and eastern Namoa Island in China; Taiwan; Metro Manila, Metro Cebu, Metro Davao and other cities in the Philippines; Singapore; Brunei; Medan, Riau and other cities in Indonesia; and from Taiping to the Thai border in Malaysia, especially around Penang.[9]

Hokkien originated in the southern area of Fujian province, an important center for trade and migration, and has since become one of the most common Chinese varieties overseas. The major pole of Hokkien varieties outside of Fujian is nearby Taiwan, where immigrants from Fujian arrived as workers during the 40 years of Dutch rule, fleeing the Qing dynasty during the 20 years of Ming loyalist rule, as immigrants during the 200 years of Qing dynasty rule, especially in the last 120 years after immigration restrictions were relaxed, and even as immigrants during the period of Japanese rule. The Taiwanese dialect mostly has origins with the Tung'an, Quanzhou and Zhangzhou variants, but since then, the Amoy dialect, also known as the Xiamen dialect, has become the modern prestige representative for the language in China. Both Amoy and Xiamen come from the Chinese name of the city (Chinese: 厦门; pinyin: Xiàmén; Pe̍h-ōe-jī: Ē-mûi); the former is from Zhangzhou Hokkien, whereas the latter comes from Mandarin.

There are many Minnan (Hokkien) speakers among overseas Chinese in Southeast Asia as well as in the United States (Hoklo Americans). Many ethnic Han Chinese emigrants to the region were Hoklo from southern Fujian, and brought the language to what is now Burma (Myanmar), Vietnam, Indonesia (the former Dutch East Indies) and present day Malaysia and Singapore (formerly Malaya and the British Straits Settlements). Most of the Minnan dialects of this region have incorporated some foreign loanwords. Hokkien is reportedly the native language of up to 80% of the ethnic Chinese people in the Philippines, among which is known locally as Lán-nâng-uē or Lán-lâng-ōe or Nán-nâng-uē ("Our people's speech"). Hokkien speakers form the largest group of overseas Chinese in Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia and Philippines.[citation needed]

Classification

Locations of Hokkien (Quanzhang) varieties in Fujian

Southern Fujian is home to four principal Minnan Proper (Hokkien) dialects: Chiangchew, Chinchew, Tung'an, and Amoy,[15] originating from the cities of Quanzhou, Zhangzhou, historical Tung'an County (同安縣, now Xiamen and Kinmen) and her own Port of Amoy, respectively.

The Quanzhou dialect spoken in Quanzhou was the Traditional Representative Minnan. It is the dialect that is used in Liyuan Opera (梨园戏) and Nanguan music (南音). The Quanzhou dialect is considered to be the most conservative Minnan dialect.

In the late 1800s, the Amoy dialect attracted special attention, because Amoy was one of the five ports opened to foreign trade by the Treaty of Nanking, but before that it had not attracted attention.[16] The Amoy dialect is adopted as the Modern Representative Minnan. The Amoy dialect can not simply be interpreted as a mixture of the Zhangzhou and Quanzhou dialects, but rather it is formed on the foundation of the Tung'an dialect with further inputs from other sub-dialects.[17] It has played an influential role in history, especially in the relations of Western nations with China, and was one of the most frequently learnt dialect of the Hokkien variety by Westerners during the second half of the 19th century and the early 20th century.

The Modern Representative form of Hokkien spoken around the city of Tainan (台南) in Taiwan heavily resembles the Tung'an dialect.[18][19] All Hokkien dialects spoken throughout the whole of Taiwan are collectively known as Taiwanese Hokkien, or Holo locally, although there is a tendency to call these Taiwanese language for historical reasons. It is spoken by more Taiwanese than any Sinitic language except Mandarin, and it is known by a majority of the population;[20] thus, from a socio-political perspective, it forms a significant pole of language usage due to the popularity of Holo-language media. Douglas (1873/1899) also noted that Formosa (Taiwan) has been settled mainly by emigrants from Amoy (Xiamen), Chang-chew (Zhangzhou), and Chin-chew (Quanzhou). Several parts of the island are usually found to be specially inhabited by descendants of such emigrants, but in Taiwan, the various forms of the dialects mentioned prior are a good deal mixed up.[21]

Southeast Asia

The varieties of Hokkien in Southeast Asia originate from these dialects. Douglas (1873/1899) notes that "Singapore and the various Straits Settlements [such as Penang and Malacca], Batavia [Jakarta] and other parts of the Dutch possessions [Indonesia], are crowded with emigrants, especially from the Chang-chew [Zhangzhou] prefecture; Manila and other parts of the Philippines have great numbers from Chin-chew [Quanzhou], and emigrants are largely scattered in like manner in Siam [Thailand], Burmah [Myanmar], the Malay Peninsula [Peninsular Malaysia], Cochin China [Southern Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos], Saigon [Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam], &c. In many of these places there is also a great mixture of emigrants from Swatow [Shantou]."[21]

In modern times though, a mixed dialect descended from the Quanzhou, Amoy, and Zhangzhou dialects, leaning a little closer to the Quanzhou dialect, possibly due to being from the Tung'an dialect, is spoken by Chinese Singaporeans, Southern Malaysian Chinese, and Chinese Indonesians in Indonesia's Riau province and Riau Islands. Variants include Southern Peninsular Malaysian Hokkien and Singaporean Hokkien in Singapore.

Among Malaysian Chinese of Penang, and other states in Northern Peninsular Malaysia and ethnic Chinese Indonesians in Medan, with other areas in North Sumatra, Indonesia, a distinct descendant dialect form of Zhangzhou Hokkien has developed. In Penang, it is called Penang Hokkien while across the Malacca Strait in Medan, an almost identical variant is known as Medan Hokkien .

As for Chinese Filipinos in the Philippines, a variant known as Philippine Hokkien, which is also mostly derived from Quanzhou Hokkien, particularly the Jinjiang and Nan'an dialects with a bit of influence from the Amoy (Xiamen) dialect, is still spoken amongst families as most also profess ancestors from the aforementioned areas.

There are also Hokkien speakers scattered throughout other parts of Indonesia (such as Jakarta and around the island of Java), Thailand (especially Southern Thailand on the border with Malaysia), Myanmar, other parts of Malaysia (such as Eastern (Insular) Malaysia), Brunei, Cambodia, and Southern Vietnam (such as in Saigon / Ho Chi Minh City), though there are notably more of Teochew/Swatow background among descendants of Chinese migrants in regions such as parts of Peninsular Malaysia, Thailand, Cambodia, Laos, and Southern Vietnam.

History[edit]

Variants of Hokkien dialects can be traced to three sources of origin: Tong'an, Quanzhou and Zhangzhou. Both Amoy and most Taiwanese are heavily based on the Tong'an dialect, and to a lesser extent, on Quanzhou and Zhangzhou dialects, while the rest of the Hokkien dialects spoken in South East Asia are derived their respective homelands in southern Fujian.

Southern Fujian

Miền nam Phúc Kiến

During the Three Kingdoms period of ancient China, there was constant warfare occurring in the Central Plain of China. Northerners began to enter into Fujian region, causing the region to incorporate parts of northern Chinese dialects. However, the massive migration of northern Han Chinese into Fujian region mainly occurred after the Disaster of Yongjia. The Jìn court fled from the north to the south, causing large numbers of northern Han Chinese to move into Fujian region. They brought the Old Chinese spoken in the Central Plain of China from the prehistoric era to the 3rd century into Fujian.

Trong thời kỳ Tam Quốc Chiến, Trung quốc đã có chiến tranh liên tục xảy ra ở đồng bằng trung nguyên. Người phía Bắc bắt đầu tiến vào khu vực Phúc Kiến, khiến khu vực này kết hợp các phần của phương ngữ miền bắc Trung Quốc. Tuy nhiên, sự di cư ồ ạt của người Hán phương bắc vào khu vực Phúc Kiến xảy ra sau thảm họa Yongjia. Triều đình Tấn/Jìn chạy trốn từ bắc xuống nam, khiến một số lượng lớn người Hán du mục / nomadic tribes ở phương bắc được đưa vào khu vực Phúc Kiến. Những người Trung Quốc cổ nói tiếng thời cổ đại của đồng bằng trung nguyên từ thời tiền sử thế kỷ thứ ba vào Phúc Kiến.In 677 (during the reign of Emperor Gaozong of Tang), Chen Zheng, together with his son Chen Yuanguang, led a military expedition to suppress a rebellion of the She people. In 885, (during the reign of Emperor Xizong of Tang), the two brothers Wang Chao and Wang Shenzhi, led a military expedition force to suppress the Huang Chao rebellion.[22] Waves of migration from the north in this era brought the language of Middle Chinese into the Fujian region.

Năm 677 (dưới thời trị vì của Hoàng đế Cao Tông nhà Đường), Trần Chính cùng với con trai là Trần Ngọc Tông, đã dẫn đầu một đoàn thám hiểm quân sự để đàn áp một cuộc nổi loạn của người Đổng. Năm 885, (dưới thời trị vì của Hoàng đế Xizong của nhà Đường), hai anh em Wang Chao và Wang Shenzhi, đã lãnh đạo một lực lượng viễn chinh quân sự để đàn áp cuộc nổi dậy của Hoàng Chao. Làn sóng di cư từ phương bắc trong thời đại này đã đưa ngôn ngữ của người Trung Quốc thời trung cổ vào khu vực Phúc Kiến.

Như vậy, miền nam Phúc Kiến đã có hai lần tiếp nhận ngôn ngữ, một đợt ngôn ngữ của di dân từ thời cổ đại thời Tam Quốc và một đợt di dân của những người trung đại thời Đuờng.

Xiamen (Amoy)

The Amoy dialect is the main dialect spoken in area of Port of Xiamen, that is, southwest corner of Xiamen island in the Chinese city of Xiamen (formerly romanized and natively pronounced as "Amoy"). Historically, Port of Xiamen had always been part of Tung'an country until after 1912 of Republic of China era. Amoy dialect cannot simply be interpreted as a mixture of Zhangzhou and Quanzhou dialects, but rather it is formed on the foundation of Tung'an dialect with further inputs from other sub-dialects,[17] namely from the adjacent Zhangzhou dialect. Phương ngữ Hạ Môn/Amoy phương ngữ Chương Châu và Tuyền Châu, mà nó được hình thành trên nền tảng của phương ngữ Tung'an với đầu vào thêm từ các phương ngữ phụ khác,[17] cụ thể là từ phương ngữ Chương Châu liền kề. Phương ngữ Hạ Môn được coi là mang tính chất nguyên thủy nhất của miền nam Phúc Kiến, không bị pha trộn hay bị hỗn tạp của những ngôn ngữ địa phương khác.

Early sources[edit]

Several playscripts survive from the late 16th century, written in a mixture of Quanzhou and Chaozhou dialects. The most important is the Romance of the Litchi Mirror, with extant manuscripts dating from 1566 and 1581.[23][24]

In the early 17th century, Spanish missionaries in the Philippines produced materials documenting the Hokkien varieties spoken by the Chinese trading community who had settled there in the late 16th century:[23][25]

These texts appear to record a Zhangzhou dialect, from the old port of Yuegang (modern-day Haicheng, an old port that is now part of Longhai).[29]

Chinese scholars produced rhyme dictionaries describing Hokkien varieties at the beginning of the 19th century:[30]

Walter Henry Medhurst based his 1832 dictionary on the latter work.

Phonology[edit]

Hokkien has one of the most diverse phoneme inventories among Chinese varieties, with more consonants than Standard Mandarin and Cantonese. Vowels are more-or-less similar to that of Mandarin. Hokkien varieties retain many pronunciations that are no longer found in other Chinese varieties. These include the retention of the /t/ initial, which is now /tʂ/ (Pinyin 'zh') in Mandarin (e.g. 'bamboo' 竹 is tik, but zhú in Mandarin), having disappeared before the 6th century in other Chinese varieties.[31] Along with other Min languages, which are not directly descended from Middle Chinese, Hokkien is of considerable interest to historical linguists for reconstructing Old Chinese.

Finals[edit]

Unlike Mandarin, Hokkien retains all the final consonants corresponding to those of Middle Chinese. While Mandarin only preserves the n and ŋ finals, Southern Min also preserves the m, p, t and k finals and developed the ʔ (glottal stop).

The vowels of Hokkien are listed below:[32]

| Oral | Nasal | Stops | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medial | ∅ | e | i | o | u | ∅ | m | n | ŋ | i | u | p | t | k | ʔ | ||

| Nucleus | Vowel | a | a | ai | au | ã | ãm | ãn | ãŋ | ãĩ | ãũ | ap | at | ak | aʔ | ||

| i | i | io | iu | ĩ | ĩm | ĩn | ĩŋ | ĩũ | ip | it | ik | iʔ | |||||

| e | e | ẽ | eŋ* | ek* | eʔ | ||||||||||||

| ə | ə | əm* | ən* | ə̃ŋ* | əp* | ət* | ək* | əʔ* | |||||||||

| o | o | oŋ* | ot* | ok* | oʔ | ||||||||||||

| ɔ | ɔ | ɔ̃ | ɔm* | ɔn* | ɔ̃ŋ | ɔp* | ɔt* | ɔk | ɔʔ | ||||||||

| u | u | ue | ui | ũn | ũĩ | ut | uʔ | ||||||||||

| ɯ | ɯ* | ɯŋ | |||||||||||||||

| Diphthongs | ia | ia | iau | ĩã | ĩãm | ĩãn | ĩãŋ | ĩãũ | iap | iat | iak | iaʔ | |||||

| iɔ | ĩɔ̃* | ĩɔ̃ŋ | iɔk | ||||||||||||||

| iə | iə | iəm* | iən* | iəŋ* | iəp* | iət* | |||||||||||

| ua | ua | uai | ũã | ũãn | ũãŋ* | ũãĩ | uat | uaʔ | |||||||||

| Others | ∅ | m̩ | ŋ̍ | ||||||||||||||

(*) Only certain dialects

- Oral vowel sounds are realized as nasal sounds when preceding a nasal consonant.

- [õ] only occurs within triphthongs as [õãĩ].

The following table illustrates some of the more commonly seen vowel shifts. Characters with the same vowel are shown in parentheses.

| English | Chinese character | Accent | Pe̍h-ōe-jī | IPA | Teochew Peng'Im |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| two | 二 | Quanzhou, Taipei | lī | li˧ | jĭ (zi˧˥)[33] |

| Xiamen, Zhangzhou, Tainan | jī | ʑi˧ | |||

| sick | 病 (生) | Quanzhou, Xiamen, Taipei | pīⁿ | pĩ˧ | pēⁿ (pẽ˩) |

| Zhangzhou, Tainan | pēⁿ | pẽ˧ | |||

| egg | 卵 (遠) | Quanzhou, Xiamen, Taiwan | nn̄g | nŋ˧ | nn̆g (nŋ˧˥) |

| Zhangzhou, Yilan[34] | nūi | nui˧ | |||

| chopsticks | 箸 (豬) | Quanzhou | tīr | tɯ˧ | tēu (tɤ˩) |

| Xiamen, Taipei | tū | tu˧ | |||

| Zhangzhou, Tainan | tī | ti˧ | |||

| shoes | 鞋 (街) | ||||

| Quanzhou, Xiamen, Taipei | oê | ue˧˥ | ôi | ||

| Zhangzhou, Tainan | ê | e˧˥ | |||

| leather | 皮 (未) | Quanzhou | phêr | pʰə˨˩ | phuê (pʰue˩) |

| Xiamen, Taipei | phê | pʰe˨˩ | |||

| Zhangzhou, Tainan | phôe | pʰue˧ | |||

| chicken | 雞 (細) | Quanzhou, Xiamen, Taipei | koe | kue˥ | koi |

| Zhangzhou, Tainan | ke | ke˥ | |||

| hair | 毛 (兩) | Quanzhou, Taiwan, Xiamen | mn̂g | mŋ | mo |

| Zhangzhou, Taiwan | mo͘ | mɔ̃ | |||

| return | 還 | Quanzhou | hoan | huaⁿ | huêng |

| Xiamen | hâiⁿ | hãɪ˨˦ | |||

| Zhangzhou, Taiwan | hêng | hîŋ | |||

| Speech | 話 (花) | Quanzhou, Taiwan | oe | ue | |

| Zhangzhou | oa | ua |

Initials[edit]

Southern Min has aspirated, unaspirated as well as voiced consonant initials. For example, the word khui (開; "open") and kuiⁿ (關; "close") have the same vowel but differ only by aspiration of the initial and nasality of the vowel. In addition, Southern Min has labial initial consonants such as m in m̄-sī (毋是; "is not").

Another example is ta-po͘-kiáⁿ (查埔囝; "boy") and cha-bó͘-kiáⁿ (查某囝; "girl"), which differ in the second syllable in consonant voicing and in tone.

| Labial | Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| voiceless Stop | plain | p | t | k | ʔ | |

| aspirated | pʰ | tʰ | kʰ | |||

| voiced stop | oral or lateral | b (m) |

d[35]~l (n) |

ɡ (ŋ) |

||

| (nasalized) | ||||||

| Affricate | plain | ts | ||||

| aspirated | tsʰ | |||||

| voiced | dz[36]~l~ɡ | |||||

| Fricative | s | h | ||||

| Semi-vowels | w | j | ||||

Tones[edit]

According to the traditional Chinese system, Hokkien dialects have 7 or 8 distinct tones, including two entering tones which end in plosive consonants. The entering tones can be analysed as allophones, giving 5 or 6 phonemic tones. In addition, many dialects have an additional phonemic tone ("tone 9" according to the traditional reckoning), used only in special or foreign loan words.[40] This means that Hokkien dialects have between 5 and 7 phonemic tones.

Tone sandhi is extensive.[41] There are minor variations between the Quanzhou and Zhangzhou tone systems. Taiwanese tones follow the patterns of Amoy or Quanzhou, depending on the area of Taiwan.

| Tones | level | rising | departing | entering | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| dark level | light level | dark rising | light rising | dark departing | light departing | dark entering | light entering | ||

| Tone Number | 1 | 5 | 2 | 6 | 3 | 7 | 4 | 8 | |

| Tone contour | Xiamen, Fujian | ˦˦ | ˨˦ | ˥˧ | – | ˨˩ | ˨˨ | ˧˨ | ˦ |

| 東 taŋ1 | 銅 taŋ5 | 董 taŋ2 | – | 凍 taŋ3 | 動 taŋ7 | 觸 tak4 | 逐 tak8 | ||

| Taipei, Taiwan | ˦˦ | ˨˦ | ˥˧ | – | ˩˩ | ˧˧ | ˧˨ | ˦ | |

| – | |||||||||

| Tainan, Taiwan | ˦˦ | ˨˧ | ˦˩ | – | ˨˩ | ˧˧ | ˧˨ | ˦˦ | |

| – | |||||||||

| Zhangzhou, Fujian | ˧˦ | ˩˧ | ˥˧ | – | ˨˩ | ˨˨ | ˧˨ | ˩˨˩ | |

| – | |||||||||

| Quanzhou, Fujian | ˧˧ | ˨˦ | ˥˥ | ˨˨ | ˦˩ | ˥ | ˨˦ | ||

| – | |||||||||

| Penang, Malaysia[42] | ˧˧ | ˨˧ | ˦˦˥ | – | ˨˩ | ˧ | ˦ | ||

| – | |||||||||

Dialects[edit]

The Hokkien language (Minnan) is spoken in a variety of accents and dialects across the Minnan region. The Hokkien spoken in most areas of the three counties of southern Zhangzhou have merged the coda finals -n and -ng into -ng. The initial consonant j (dz and dʑ) is not present in most dialects of Hokkien spoken in Quanzhou, having been merged into the d or l initials.

The -ik or -ɪk final consonant that is preserved in the native Hokkien dialects of Zhangzhou and Xiamen is also preserved in the Nan'an dialect (色, 德, 竹) but are pronounce as -iak in Quanzhou Hokkien.[43]

- Longxi dialect (龍溪話)

- Longyan dialect (龍巖話)

- Pinghe dialect (平和話)

- Yunxiao dialect (雲霄話)

- Zhangpu dialect (漳浦話)

- Zhangzhou dialect (漳州話)

- Zhao'an dialect (詔安話)

- Haifeng dialect (海豐話)

- Lufeng dialect (陸豐話)

- Penang Hokkien (檳城/庇能福建話)

- Medan Hokkien (棉蘭福建話)

Comparison[edit]

The Amoy dialect (Xiamen) is a variant of Tung'an dialect. Majority of Taiwanese, from Tainan, to Taichung, to Taipei, is also heavily based on Tung'an dialect while incorporating some vowels of Zhangzhou dialect, whereas Southern Peninsular Malaysian Hokkien, including Singaporean Hokkien, is based on the Tung'an dialect, with Philippine Hokkien on the Quanzhou dialect, and Peneng Hokkien on Zhangzhou dialect. There are some variations in pronunciation and vocabulary between Quanzhou and Zhangzhou dialects. The grammar is generally the same.

Additionally, extensive contact with the Japanese language has left a legacy of Japanese loanwords in Taiwanese Hokkien. On the other hand, the variants spoken in Singapore and Malaysia have a substantial number of loanwords from Malay and to a lesser extent, from English and other Chinese varieties, such as the closely related Teochew and some Cantonese. Meanwhile, in the Philippines, there are also a few Spanish and/or Filipino (Tagalog) loanwords, while it is also currently a norm to frequently codeswitch with English and Filipino (Tagalog), or other Philippine languages, such as Bisaya.

Mutual intelligibility[edit]

Tong'an, Xiamen, Taiwanese, Singaporean dialects as a group are more mutually intelligible, but it is less so amongst the forementioned group, Quanzhou dialect, and Zhangzhou dialect.[44]

Although the Min Nan varieties of Teochew and Amoy are 84% phonetically similar including the pronunciations of un-used Chinese characters as well as same characters used for different meanings,[citation needed] and 34% lexically similar,[citation needed], Teochew has only 51% intelligibility with the Tung'an dialect (Cheng 1997)[who?] whereas Mandarin and Amoy Min Nan are 62% phonetically similar[citation needed] and 15% lexically similar.[citation needed] In comparison, German and English are 60% lexically similar.[45]

Hainanese, which is sometimes considered Southern Min, has almost no mutual intelligibility with any form of Hokkien.[44]

Grammar[edit]

Hokkien is an analytic language; in a sentence, the arrangement of words is important to its meaning.[46] A basic sentence follows the subject–verb–object pattern (i.e. a subject is followed by a verb then by an object), though this order is often violated because Hokkien dialects are topic-prominent. Unlike synthetic languages, seldom do words indicate time, gender and plural by inflection. Instead, these concepts are expressed through adverbs, aspect markers, and grammatical particles, or are deduced from the context. Different particles are added to a sentence to further specify its status or intonation.

A verb itself indicates no grammatical tense. The time can be explicitly shown with time-indicating adverbs. Certain exceptions exist, however, according to the pragmatic interpretation of a verb's meaning. Additionally, an optional aspect particle can be appended to a verb to indicate the state of an action. Appending interrogative or exclamative particles to a sentence turns a statement into a question or shows the attitudes of the speaker.

Hokkien dialects preserve certain grammatical reflexes and patterns reminiscent of the broad stage of Archaic Chinese. This includes the serialization of verb phrases (direct linkage of verbs and verb phrases) and the infrequency of nominalization, both similar to Archaic Chinese grammar.[47]

汝

Lí

You

去

khì

go

買

bué

buy

有

ū

have

錶仔

pió-á

watch

無?

--bô?

no

"Did you go to buy a watch?"

Choice of grammatical function words also varies significantly among the Hokkien dialects. For instance, khit (乞) (denoting the causative, passive or dative) is retained in Jinjiang (also unique to the Jinjiang dialect is thō͘ 度) and in Jieyang, but not in Longxi and Xiamen, whose dialects use hō͘ (互/予) instead.[48]

Pronouns[edit]

Hokkien dialects differ in the pronunciation of some pronouns (such as the second person pronoun lí or lú or lír), and also differ in how to form plural pronouns (such as -n or -lâng). Personal pronouns found in the Hokkien dialects are listed below:

| Singular | Plural | |

|---|---|---|

| 1st person | 我 góa |

阮1gún, góan 咱2 or 俺 lán or án 我儂1,3 góa-lâng |

| 2nd person | 汝 lí, lír, lú |

恁 lín 汝儂3 lí-lâng, lú-lâng |

| 3rd person | 伊 i |

𪜶 in 伊儂3 i-lâng |

- 1 Exclusive

- 2 Inclusive

- 3 儂 (-lâng) is typically suffixed in Southeast Asian Hokkien dialects (with the exception of Philippine Hokkien)

Possessive pronouns can be marked by the particle ê (的), in the same way as normal nouns. In some dialects, possessive pronouns can also be formed with a nasal suffix, which means that possessive pronouns and plural pronouns are homophones:[49]

The most common reflexive pronoun is ka-kī (家己). In formal contexts, chū-kí (自己) is also used.

Hokkien dialects use a variety of demonstrative pronouns, which include:

The interrogative pronouns include:

Copula ("to be")

States and qualities are generally expressed using stative verbs that do not require the verb "to be":

我

goá

I

腹肚

pak-tó͘

stomach

枵。

iau.

hungry

"I am hungry."

With noun complements, the verb sī (是) serves as the verb "to be".

昨昏

cha-hng

是

sī

八月節。

poeh-ge̍h-choeh.

"Yesterday was the Mid-Autumn festival."

To indicate location, the words tī (佇) tiàm (踮), leh (咧), which are collectively known as the locatives or sometimes coverbs in Chinese linguistics, are used to express "(to be) at":

我

goá

踮

tiàm

遮

chia

等

tán

汝。

lí.

"I am here waiting for you."

伊

i

這摆

chit-mái

佇

tī

厝

chhù

裡

lāi

咧

leh

睏。

khùn.

"They're sleeping at home now."

Negation[]

Hokkien dialects have a variety of negation particles that are prefixed or affixed to the verbs they modify. There are six primary negation particles in Hokkien dialects (with some variation in how they are written in characters):

- m̄ (毋, 呣, 唔, 伓)

- bē (未)

- bōe (𣍐)

- mài (莫, 【勿愛】)

- bô (無)

- put (不) – literary

Other negative particles include:

- bâng (甭)

- bián (免)

- thài (汰)

The particle m̄ (毋, 呣, 唔, 伓) is general and can negate almost any verb:

伊

i

they

毋

m̄

not

捌

bat

know

字。

jī

word

"They cannot read."

The particle mài (莫, 【勿爱】), a concatenation of m-ài (毋愛) is used to negate imperative commands:

莫

mài

講!

kóng

"Don't speak!"

The particle bô (無) indicates the past tense:

伊

i

無

bô

食。

chia̍h

"They did not eat."

The verb 'to have', ū (有) is replaced by bô (無) when negated (not 無有):

伊

i

無

bô

錢。

chîⁿ

"They do not have any money."

The particle put (不) is used infrequently, mostly found in literary compounds and phrases:

伊

i

真

chin

不孝。

put-hàu

"They are truly unfilial."

Vocabulary[edit]

The majority of Hokkien vocabulary is monosyllabic.[50][better source needed] Many Hokkien words have cognates in other Chinese varieties. That said, there are also many indigenous words that are unique to Hokkien and are potentially not of Sino-Tibetan origin, while others are shared by all the Min dialects (e.g. 'congee' is 糜 mê, bôe, bê, not 粥 zhōu, as in other dialects).

As compared to Mandarin, Hokkien dialects prefer to use the monosyllabic form of words, without suffixes. For instance, the Mandarin noun suffix 子 (zi) is not found in Hokkien words, while another noun suffix, 仔 (á) is used in many nouns. Examples are below:

In other bisyllabic morphemes, the syllables are inverted, as compared to Mandarin. Examples include the following:

In other cases, the same word can have different meanings in Hokkien and Mandarin. Similarly, depending on the region Hokkien is spoken in, loanwords from local languages (Malay, Tagalog, Burmese, among others), as well as other Chinese dialects (such as Southern Chinese dialects like Cantonese and Teochew), are commonly integrated into the vocabulary of Hokkien dialects.

Literary and colloquial readings[edit]

The existence of literary and colloquial readings is a prominent feature of some Hokkien dialects and indeed in many Sinitic varieties in the south. The bulk of literary readings (文讀, bûn-tha̍k), based on pronunciations of the vernacular during the Tang dynasty, are mainly used in formal phrases and written language (e.g. philosophical concepts, given names, and some place names), while the colloquial (or vernacular) ones (白讀, pe̍h-tha̍k) are usually used in spoken language, vulgar phrases and surnames. Literary readings are more similar to the pronunciations of the Tang standard of Middle Chinese than their colloquial equivalents.

The pronounced divergence between literary and colloquial pronunciations found in Hokkien dialects is attributed to the presence of several strata in the Min lexicon. The earliest, colloquial stratum is traced to the Han dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE); the second colloquial one comes from the period of the Northern and Southern dynasties (420–589 CE); the third stratum of pronunciations (typically literary ones) comes from the Tang dynasty (618–907 CE) and is based on the prestige dialect of Chang'an (modern day Xi'an), its capital.[51]

Some commonly seen sound correspondences (colloquial → literary) are as follows:

This table displays some widely used characters in Hokkien that have both literary and colloquial readings:[52][53]

| Chinese character | Reading pronunciations | Spoken pronunciations / †explications | English |

|---|---|---|---|

| 白 | pe̍k | pe̍h | white |

| 面 | biān | bīn | face |

| 書 | su | chu | book |

| 生 | seng | seⁿ / siⁿ | student |

| 不 | put | m̄† | not |

| 返 | hóan | tńg† | return |

| 學 | ha̍k | o̍h | to study |

| 人 | jîn / lîn | lâng† | person |

| 少 | siàu | chió | few |

| 轉 | chóan | tńg | to turn |

This feature extends to Chinese numerals, which have both literary and colloquial readings.[53] Literary readings are typically used when the numerals are read out loud (e.g. phone numbers, years), while colloquial readings are used for counting items.

| Numeral | Reading | Numeral | Reading | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Literary | Colloquial | Literary | Colloquial | ||

| 1 | it | chi̍t | 6 | lio̍k | la̍k |

| 2 | jī, lī | nn̄g | 7 | chhit | |

| 3 | sam | saⁿ | 8 | pat | peh, poeh |

| 4 | sù, sìr | sì | 9 | kiú | káu |

| 5 | ngó͘ | gō͘ | 10 | si̍p | cha̍p |

Semantic differences between Hokkien and Mandarinedit

Quite a few words from the variety of Old Chinese spoken in the state of Wu, where the ancestral language of Min and Wu dialect families originated, and later words from Middle Chinese as well, have retained the original meanings in Hokkien, while many of their counterparts in Mandarin Chinese have either fallen out of daily use, have been substituted with other words (some of which are borrowed from other languages while others are new developments), or have developed newer meanings. The same may be said of Hokkien as well, since some lexical meaning evolved in step with Mandarin while others are wholly innovative developments.

This table shows some Hokkien dialect words from Classical Chinese, as contrasted to the written Mandarin:

--#bfdfff--| Meaning | Hokkien | Mandarin | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hanji | POJ | Hanzi | Pinyin | |

| eye | 目睭/目珠 | ba̍k-chiu | 眼睛 | yǎnjīng |

| chopstick | 箸 | tī, tīr, tū | 筷子 | kuàizi |

| to chase | 逐 | jiok, lip | 追 | zhuī |

| wet | 澹[54] | tâm | 濕 | shī |

| black | 烏 | o͘ | 黑 | hēi |

| book | 冊 | chheh | 書 | shū |

For other words, the classical Chinese meanings of certain words, which are retained in Hokkien dialects, have evolved or deviated significantly in other Chinese dialects. The following table shows some words that are both used in both Hokkien dialects and Mandarin Chinese, while the meanings in Mandarin Chinese have been modified:

| Word | Hokkien | Mandarin | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| POJ | Meaning (and Classical Chinese) |

Pinyin | Meaning | |

| 走 | cháu | to flee | zǒu | to walk |

| 細 | sè, sòe | tiny, small, young | xì | thin, slender |

| 鼎 | tiáⁿ | pot | dǐng | tripod |

| 食 | chia̍h | to eat | shí | to eat – it's the same |

| 懸 | kôan, koâiⁿ, kûiⁿ | tall, high | xuán | to hang, to suspend |

| 喙 | chhùi | mouth | huì | beak |

Words from Minyue[edit]

Some commonly used words, shared by all[citation needed][dubious ] Min Chinese languages, came from the ancient Minyue languages. Jerry Norman suggested that these languages were Austroasiatic. Some terms are thought be cognates with words in Tai Kadai and Austronesian languages. They include the following examples, compared to the Fuzhou dialect, a Min Dong language:

| Word | Hokkien POJ | Foochow Romanized | Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| 骹 | kha [kʰa˥] | kă [kʰa˥] | foot and leg |

| 囝 | kiáⁿ [kjã˥˩] | giāng [kjaŋ˧] | son, child, whelp, a small amount |

| 睏 | khùn [kʰun˨˩] | káung [kʰɑwŋ˨˩˧] | to sleep |

| 骿 | phiaⁿ [pʰjã˥] | piăng [pʰjaŋ˥] | back, dorsum |

| 厝 | chhù [tsʰu˨˩] | chuó, chió [tsʰwɔ˥˧] | home, house |

| 刣 | thâi [tʰaj˨˦] | tài [tʰaj˥˧] | to kill, to slaughter |

| (肉) | bah [baʔ˧˨] | — | meat |

| 媠 | suí [sui˥˧] | — | beautiful |

| 檨 | soāiⁿ [suãi˨˨] | suông [suɔŋ˨˦˨] | mango (Austroasiatic) [55][56] |

Loanwordsedit

Loanwords are not unusual among Hokkien dialects, as speakers readily adopted indigenous terms of the languages they came in contact with. As a result, there is a plethora of loanwords that are not mutually comprehensible among Hokkien dialects.

Taiwanese Hokkien, as a result of linguistic contact with Japanese[57] and Formosan languages, contains many loanwords from these languages. Many words have also been formed as calques from Mandarin, and speakers will often directly use Mandarin vocabulary through codeswitching. Among these include the following examples:

- 'toilet' – piān-só͘ (便所) from Japanese benjo (便所)

- Other Hokkien variants: 屎礐 (sái-ha̍k), 廁所 (chhek-só͘)

- 'car' – chū-tōng-chhia (自動車) from Japanese jidōsha (自動車)

- Other Hokkien variants: 風車 (hong-chhia), 汽車 (khì-chhia)

- 'to admire' – kám-sim (Chinese: 感心) from Japanese kanshin (感心)

- Other Hokkien variants: 感動 (kám-tōng)

- 'fruit' – chúi-ké / chúi-kóe / chúi-kér (水果) from Mandarin (水果; shuǐguǒ)

- Other Hokkien variants: 果子 (ké-chí / kóe-chí / kér-chí)

Singaporean Hokkien, Penang Hokkien and other Malaysian Hokkien dialects tend to draw loanwords from Malay, English as well as other Chinese dialects, primarily Teochew. Examples include:

- Other Hokkien variants: 但是 (tān-sī)

- Other Hokkien variants: 醫生(i-seng)

- Other Hokkien variants: 石头(chio̍h-thâu)

- Other Hokkien variants: 市場 (chhī-tiûⁿ), 菜市 (chhài-chhī)

- Other Hokkien variants: 𪜶 (in)

- Other Hokkien variants: 做夥 (chò-hóe), 同齊 (tâng-chê) or 鬥陣 (tàu-tīn)

Philippine Hokkien, as a result of centuries-old contact with both Philippine languages and Spanish also incorporate words from these languages. Speakers today will also often directly use English and Filipino (Tagalog), or other Philippine languages like Bisaya, vocabulary through codeswitching. Examples include:

- Other Hokkien variants: 杯仔 (poe-á), 杯 (poe)

- Other Hokkien variants: 辦公室 (pān-kong-sek/pān-kong-siak)

- Other Hokkien variants:

- Other Hokkien variants: 予錢 (hō͘-chîⁿ), 還錢 (hêng-chîⁿ)

- Other Hokkien variants: 咖啡 (ko-pi), 咖啡 (ka-pi)

Comparison with Mandarin and Sino-Xenic pronunciations

*****

| English | Chinese characters | Mandarin Chinese | Taiwanese Hokkien[61] | Korean | Vietnamese | Japanese |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Book | 冊 | Cè | Chheh | Chaek 책 | Tập/Sách | Saku/Satsu/Shaku |

| Bridge | 橋 | Qiáo | Kiô | Kyo | Cầu/Kiều | Kyō |

| Dangerous | 危險 | Wēixiǎn | Guî-hiám | Wiheom 위협 | Nguy hiểm | Kiken |

| Flag | 旗 | Qí | Kî | Ki | Cờ/Kỳ | Ki |

| Insurance | 保險 | Bǎoxiǎn | Pó-hiám | Boheom | Bảo hiểm | Hoken |

| News | 新聞 | Xīnwén | Sin-bûn | Shinmun 신문 | Tân Văn/tin tức | Shinbun |

| Student | 學生 | Xuéshēng | Ha̍k-seng | Haksaeng | Học sinh | Gakusei |

| University | 大學 | Dàxué | Tāi-ha̍k (Tōa-o̍h) | Daehak | Đại học | Daigaku |

Koiné Hokkien[]

Quanzhou was historically the cultural center for Hokkien, as various traditional Hokkien culture such as Nanguan music, Beiguan music, Glove puppetry, Kaoka opera (高甲戲) or Lewan opera (梨園戲) genre of Hokkien opera originated from Quanzhou. This was mainly due to the fact that Quanzhou had become an important trading and commercial port since Tang dynasty and had prospered into an important city. After the Opium War in 1842, Xiamen (Amoy) became one of the major treaty ports to be opened for trade with the outside world. From the mid-19th century onwards, Xiamen slowly developed to become the political and economical center of the Hokkien speaking region in China. This caused Amoy dialect to gradually replace the position of dialect variants from Quanzhou and Zhangzhou. From the mid-19th century until the end of World War II,[citation needed] western diplomats usually learned Amoy as the preferred dialect if they were to communicate with the Hokkien-speaking populace in China or South-East Asia. In the 1940s and 1950s, Taiwan[who?] also tended to incline towards Amoy dialect.

The retreat of the Republic of China to Taiwan in 1949 drove party leaders to seek to both culturally and politically assimilate the islanders. As a result, laws were passed throughout the 1950s to suppress Hokkien and other languages in favor of Mandarin. By 1956, speaking Hokkien in ROC schools or military bases was illegal. However, popular outcry from both older islander communities and more recent Mainlander immigrants prompted a general wave of education reform, during which these and other education restrictions were lifted. The general goal of assimilation remained, with Amoy Hokkien seen as less ‘native’ and therefore preferred.[62]

However, from the 1980s onwards, the development of Taiwanese Min Nan pop music and media industry in Taiwan caused the Hokkien cultural hub to shift from Xiamen to Taiwan.[citation needed] The flourishing Taiwanese Min Nan entertainment and media industry from Taiwan in the 1990s and early 21st century led Taiwan to emerge as the new significant cultural hub for Hokkien.

In the 1990s, marked by the liberalization of language development and mother tongue movement in Taiwan, Taiwanese Hokkien had undergone a fast pace in its development. In 1993, Taiwan became the first region in the world to implement the teaching of Taiwanese Hokkien in Taiwanese schools. In 2001, the local Taiwanese language program was further extended to all schools in Taiwan, and Taiwanese Hokkien became one of the compulsory local Taiwanese languages to be learned in schools.[63] The mother tongue movement in Taiwan even influenced Xiamen (Amoy) to the point that in 2010, Xiamen also began to implement the teaching of Hokkien dialect in its schools.[64] In 2007, the Ministry of Education in Taiwan also completed the standardization of Chinese characters used for writing Hokkien and developed Tai-lo as the standard Hokkien pronunciation and romanization guide. A number of universities in Taiwan also offer Taiwanese degree courses for training Hokkien-fluent talents to work for the Hokkien media industry and education. Taiwan also has its own Hokkien literary and cultural circles whereby Hokkien poets and writers compose poetry or literature in Hokkien.

Thus by the 21st century, Taiwan has become one of the most significant Hokkien cultural hubs of the world. The historical changes and development in Taiwan had led Taiwanese Hokkien to become the more influential pole of the Hokkien dialect after the mid-20th century. Today, the Taiwanese prestige dialect (Taiyu Youshiqiang/Tongxinqiang 台語優勢腔/通行腔) is heard on Taiwanese media.

Writing systems

Chinese script[edit]

Hokkien dialects are typically written using Chinese characters (漢字, Hàn-jī). However, the written script was and remains adapted to the literary form, which is based on classical Chinese, not the vernacular and spoken form. Furthermore, the character inventory used for Mandarin (standard written Chinese) does not correspond to Hokkien words, and there are a large number of informal characters (替字, thè-jī or thòe-jī; 'substitute characters') which are unique to Hokkien (as is the case with Cantonese). For instance, about 20 to 25% of Taiwanese morphemes lack an appropriate or standard Chinese character.[52]

While most Hokkien morphemes have standard designated characters, they are not always etymological or phono-semantic. Similar-sounding, similar-meaning or rare characters are commonly borrowed or substituted to represent a particular morpheme. Examples include "beautiful" (美 bí is the literary form), whose vernacular morpheme suí is represented by characters like 媠 (an obsolete character), 婎 (a vernacular reading of this character) and even 水 (transliteration of the sound suí), or "tall" (高 ko is the literary form), whose morpheme kôan is 懸.[65] Common grammatical particles are not exempt; the negation particle m̄ (not) is variously represented by 毋, 呣 or 唔, among others. In other cases, characters are invented to represent a particular morpheme (a common example is the character 𪜶 in, which represents the personal pronoun "they"). In addition, some characters have multiple and unrelated pronunciations, adapted to represent Hokkien words. For example, the Hokkien word bah ("meat") has been reduced to the character 肉, which has etymologically unrelated colloquial and literary readings (he̍k and jio̍k, respectively).[66][67] Another case is the word 'to eat,' chia̍h, which is often transcribed in Taiwanese newspapers and media as 呷 (a Mandarin transliteration, xiā, to approximate the Hokkien term), even though its recommended character in dictionaries is 食.[68]

Moreover, unlike Cantonese, Hokkien does not have a universally accepted standardized character set. Thus, there is some variation in the characters used to express certain words and characters can be ambiguous in meaning. In 2007, the Ministry of Education of the Republic of China formulated and released a standard character set to overcome these difficulties.[69] These standard Chinese characters for writing Taiwanese Hokkien are now taught in schools in Taiwan.

Latin script[]

Hokkien, especially Taiwanese Hokkien, is sometimes written in the Latin script using one of several alphabets. Of these the most popular is POJ, developed first by Presbyterian missionaries in China and later by the indigenous Presbyterian Church in Taiwan. Use of this script and orthography has been actively promoted since the late 19th century. The use of a mixed script of Han characters and Latin letters is also seen, though remains uncommon. Other Latin-based alphabets also exist.

Min Nan texts, all Hokkien, can be dated back to the 16th century. One example is the Doctrina Christiana en letra y lengua china, presumably written around 1593 by the Spanish Dominican friars in the Philippines.

Another is a Ming dynasty script of a play called

Tale of the Lychee Mirror (1566), supposedly the earliest Southern Min colloquial text, although it is written in Teochew dialect.

Taiwan has developed a Latin alphabet for Taiwanese Hokkien, derived from POJ, known as Tai-lo. Since 2006, it has been officially promoted by Taiwan's Ministry of Education and taught in Taiwanese schools. Xiamen University has also developed an alphabet based on Pinyin called Bbánlám pìngyīm.

Computing[edit]

Hokkien is registered as "Southern Min" per RFC 3066 as zh-min-nan.[70]

Tiếng Phúc Kiến được ghi danh là "Southern Min" trên mỗi RFC 3066 với tên zh-min-nan.

When writing Hokkien in Chinese characters, some writers create 'new' characters when they consider it impossible to use directly or borrow existing ones; this corresponds to similar practices in character usage in Cantonese, Vietnamese chữ nôm, Korean hanja and Japanese kanji. Some of these are not encoded in Unicode (or the corresponding ISO/IEC 10646: Universal Character Set), thus creating problems in computer processing.

Khi viết tiếng Phúc Kiến bằng chữ Hán, một số nhà văn tạo ra các ký tự 'mới' khi họ cho rằng không thể sử dụng trực tiếp hoặc mượn các ký tự hiện có; điều này tương đ ư ơng với các thông lệ tương tự trong việc sử dụng ký tự trong tiếng Quảng Đông, chữ nôm tiếng Việt, hanja Hàn Quốc và kanji Nhật Bản. Một số trong số này không được mã hóa bằng Unicode (hoặc ISO / IEC 10646: Universal Character Set tương đ ư ơng), do đó tạo ra các vấn đề khó khăn trong quá trình giải quyết máy điện toán.

All Latin characters required by Pe̍h-ōe-jī can be represented using Unicode (or the corresponding ISO/IEC 10646: Universal Character Set), using precomposed or combining (diacritics) characters. Prior to June 2004, the vowel akin to but more open than o, written with a dot above right, was not encoded. The usual workaround was to use the (stand-alone; spacing) character Interpunct (U+00B7, ·) or less commonly the combining character dot above (U+0307). As these are far from ideal, since 1997 proposals have been submitted to the ISO/IEC working group in charge of ISO/IEC 10646—namely, ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2—to encode a new combining character dot above right. This is now officially assigned to U+0358 (see documents N1593, N2507, N2628, N2699, and N2713).

Cultural and political role [edit]

Hokkien (or Min Nan) can trace its roots through the Tang dynasty and also even further to the people of the Minyue, the indigenous non-Han people of modern-day Fujian.[71] Min Nan (Hokkien) people call themselves "Tang people," (唐人; Tn̂g-lâng) which is synonymous to "Chinese people". Because of the widespread influence of the Tang culture during the great Tang dynasty, there are today still many Min Nan pronunciations of words shared by the Vietnamese, Korean and Japanese languages.

In 2002, the Taiwan Solidarity Union, a party with about 10% of the Legislative Yuan seats at the time, suggested making Taiwanese a second official language.[72] This proposal encountered strong opposition not only from Mainlander groups but also from Hakka and Taiwanese aboriginal groups who felt that it would slight their home languages. Because of these objections, support for this measure was lukewarm among moderate Taiwan independence supporters, and the proposal did not pass.

Hokkien was finally made an official language of Taiwan in 2018 by the ruling DPP government.

..........................................................

| Letter | Aa | Bb | Cc | Dd | Ee | Ff | Gg | Hh | Ii | Jj | Kk | Ll | Mm | Nn | Oo | Pp | Rr | Ss | Tt | Uu | Vv | Ww | Xx | Yy | Zz | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pronunciation (pinyin) | a | bê | cê | dê | e | f | gê | ha | i | jie | kê | l | êm | nê | o | pê | qiu | ar | ês | tê | wu | vê | wa | xi | ya | zê |

| Bopomofo transcription | ㄚ | ㄅㄝ | ㄘㄝ | ㄉㄝ | ㄜ | ㄝㄈ | ㄍㄝ | ㄏㄚ | ㄧ | ㄐㄧㄝ | ㄎㄝ | ㄝㄌ | ㄝㄇ | ㄋㄝ | ㄛ | ㄆㄝ | ㄑㄧㄡ | ㄚㄦ | ㄝㄙ | ㄊㄝ | ㄨ | ㄪㄝ | ㄨㄚ | ㄒㄧ | ㄧㄚ | ㄗㄝ |

*********************************

| Letter | Aa | Bb | Cc | Dd | Ee | Ff | Gg | Hh | Ii | Jj | Kk | Ll | Mm | Nn | Oo | Pp | Rr | Ss | Tt | Uu | Vv | Ww | Xx | Yy | Zz | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pronunciation (pinyin) | a | bê | cê | dê | e | f | gê | ha | i | jie | kê | l | êm | nê | o | pê | qiu | ar | ês | tê | wu | vê | wa | xi | ya | zê |

| Bopomofo transcription | ㄚ | ㄅㄝ | ㄘㄝ | ㄉㄝ | ㄜ | ㄝㄈ | ㄍㄝ | ㄏㄚ | ㄧ | ㄐㄧㄝ | ㄎㄝ | ㄝㄌ | ㄝㄇ | ㄋㄝ | ㄛ | ㄆㄝ | ㄑㄧㄡ | ㄚㄦ | ㄝㄙ | ㄊㄝ | ㄨ | ㄪㄝ | ㄨㄚ | ㄒㄧ | ㄧㄚ | ㄗㄝ |

* Các ký hiệu phụ âm tương đương pinyin

ㄅ = b ㄆ = p ㄇ = m ㄈ = f ㄉ = d ㄊ = t ㄋ = n ㄌ = l ㄍ = g ㄎ = k ㄏ = h ㄐ = j ㄑ = q ㄒ = x ㄓ = zh ㄔ = ch ㄕ = sh ㄖ = r ㄗ = z ㄘ = c ㄙ = s

* Các ký hiệu nguyên âm tương đương với pinyin

ㄧ = i ㄨ = u ㄩ = ü ㄚ = a ㄛ = o ㄜ = e ㄝ = ie ㄞ = ai ㄟ = ei ㄠ = ao ㄡ = ou ㄢ = an ㄣ = en / n ㄤ = ang ㄥ = eng / ng ㄦ = er / r ㄩㄥ = iong ㄨㄥ = ong ㄧㄥ = ing ㄧㄣ = in ㄧㄝ = ie ㄩㄝ = üe

- (The voyager clip says: Thài-khong pêng-iú, lín-hó. Lín chia̍h-pá--bē? Ū-êng, to̍h lâi gún chia chē--ô͘! 太空朋友,恁好。恁食飽未?有閒著來阮遮坐哦!)

***************************************

Mân Việt / Minnan

Cuộc tấn công của nước Sở đã cắt đôi lãnh thổ nước Việt, bấy giờ phần phía bắc của nước Việt đang giáp với nước Tề. Sau nhiều năm kháng cự, cuối cùng nước Việt cũng bị nước Sở tiêu diệt, Việt vương Vô Cương thất trận và bị giết. Lãnh thổ nước Việt bị nước Sở và nước Tề sáp nhập. Con thứ hai của Vô Cương là Minh Di được vua Sở cho cai quản vùng đất Ngô Thành (nay ở huyện Ngô Hưng tỉnh Chiết Giang).

Nước Việt thuộc dòng dõi thế nào, vẫn còn nhiều tranh cãi, có hai thuyết:

1- Là hậu duệ Quốc vương nước Sở,

2- Là dòng dõi Hạ Vũ, được phong ở đất Cối Kê để lo việc phụng thờ.

Lãnh thổ quốc gia này hiện tại ở vùng đất phía nam Trường Giang, ven biển Chiết Giang.

Giang Nam (Jiang Nam) là một khu vực địa lý ở Trung Quốc đề cập đến các vùng đất ngay phía nam của vùng hạ lưu của sông Dương Tử, bao gồm cả phần phía nam của đồng bằng sông Dương Tử. Khu vực này bao gồm đô thị Thượng Hải, phần phía nam của tỉnh Giang Tô, phần phía nam của tỉnh An Huy, phần phía bắc của tỉnh Giang Tây và phần phía bắc của tỉnh Chiết Giang.

Nước Việt cổ đại

Ancient Việt Dynasty

" ... Trong vòng năm dặm từ Giao Chỉ đến Cối Kê (trong khu vực phía nam sông Dương Tử), người dân Bách Việt có thể được tìm thấy ở khắp mọi nơi, mỗi nhóm có phong tục khu vực riêng."

Hình: Thủ đô của đất nước Minyue là Dongyue và vẫn còn bằng chứng khảo cổ học về các ngôi mộ hoàng gia Minyue trong đó.

Hình: Người Hán gốc Hán du mục chuyển đến cai trị ở đây và đồng hóa người Minyue/Mân Việt.

Bài học lịch sử

Vua Minyue/Mân Việt đầu hàng vì ông hy vọng rằng đầu hàng như thế có thể cứu cung điện và người dân của họ. Quân Hán Trung Quốc đồng ý (giả vờ đồng ý?), nhưng sau đó họ bắt nhốt người, đốt thủ đô, đốt lăng mộ, sách vở và những thứ khác... thành tro bụi.

(Người Yue/Việt đã không học bài học của nhà Tần là Tần Thủy Hoàng khi tiêu diệt sáu nước phía bắc sông Hoàng Hà, vua Tần Thủy Hoàng kêu gọi các ông vua bị chiến bại hãy ra đầu hàng, nộp tướng lãnh, vũ khí thì sẽ được tha tội, để làm yên lòng các vị vua chúa đó. Thế nhưng các vua bị bại trận họ tin lời hứa hão của vua Tần và ra tự nộp mình cho vua Tần (thay vì đi trốn hoặc đánh trả cho tới chết). Hỡi ôi! Cách chiêu dụ nói láo chỉ giúp vua Tần dễ tiêu diệt nhanh, nhiều, gọn, kẻ bại trận mà thôi. Thì vua Minyue, nếu vua không tin lời người Tần cứ tiếp tục chiến đấu thì vua và quan tướng lãnh có thể bị chết nhưng lăng mộ, đền đài, sách vở, không thành tro bụi.

Người Yue/Việt cuối cùng đứng ra chiến đấu chống lại nhà Hán tên là Sơn Việt/Shanyue trong thời kỳ tam quốc cho đến khi họ thất bại, dẫu là thất bại nhưng không tự nộp mình cho giặc để giặc giết một cách dễ dàng như con ngóe.

Những bộ lạc hay quốc gia do các nhà quý tộc người Việt lập ở miền Lĩnh Nam, người Hán tộc gọi chung là Bách Việt. Ban đầu, những nhóm quan trọng ở miền Chiết Giang, Phúc Kiến đều ảnh hưởng từ nước Sở, thế nhưng, những nhóm ở xa hơn trong miền Quảng Tây, Quảng Đông và Bắc Kỳ (miền Bắc Việt Nam ngày nay) thì không bị Sở ky mi.

Hình: Vào thời điểm chị em Trưng bắt đầu tập hợp người dân Bách Việt, các vương quốc còn lại trông như thế này.

Sự ra đi của Giang Nam (Ư Việt và Mân Việt) thật đau lòng cho người dân của tôi. Chúng tôi đã viết những bài hát và bài thơ, ghi lại sự mất mát này, một trong số đó là một bài hát dân gian nổi tiếng mang tên Lý Giang Nam. Giang Nam từ lâu đã được coi là một trong những khu vực thịnh vượng nhất ở Trung Quốc do sự giàu có về tài nguyên thiên nhiên và sự phát triển của con người rất cao.

Trở lại những ngày Mà Giang Nam vẫn còn là Nam Giang, nó không lớn bằng Giang Nam ngày nay do một con sông cắt qua hai phần ba diện tích của khu vực. Con sông đó là một đường phân định ranh giới tự nhiên cho hai quốc gia riêng biệt, người Hán và người Bách Việt. Sau khi Giang Tên bị vượt qua, thành phố đã được mở rộng, và bây giờ lớn hơn nhiều so với thành phố biên giới như trước đây, từ lâu.

Con tằm đại diện cho ngành kỹ nghệ tơ lụa, Lụa tơ tằm chính yếu được sản xuất ở các khu vực phía Nam của đồng bằng sông Dương Tử, nơi chính xác là Giang Nam hiện đang tọa lạc. Lụa là thứ mà người Việt chúng tôi đã trau dồi trong một thời gian rất dài. Chúng tôi vẫn làm. Có rất nhiều làng nghề sản xuất lụa nổi tiếng ở Việt Nam, nhưng không có làng nào nổi tiếng hơn lụa Giang Nam.

Hơn trăm năm sau Câu Tiễn (năm thứ 46 đời Chu Hiến Vương, tức năm 333 tcn) nước Việt bị nước Sở diệt, từ đó người Việt lìa tan, và di tản xuống Giang Nam, sống rải rác ở miền bờ biển lục địa Đông Nam Á này. Ở đấy, họ gặp những người đồng chủng tộc Việt đã định cư hay di cư đến từ trước. Song người nước Việt có lẽ đã đạt đến một trình độ văn hóa cao hơn, cho nên sau khi họ di cư sống chung với những người thị tộc ở miền Nam trước họ, thì người nước Việt [Việt Quốc/hậu duệ vua Câu Tiễn] đã đem đến đó một hình thức chính trị, và có lẽ một hình thức kinh tế cao hơn.

Những nhà quý tộc người Việt/Việt quốc mới tụ họp với các nhóm Việt tộc cũ, hoặc lập thành những bộ lạc lớn mà tự xưng là quận trưởng (lão trưởng), hoặc cao hơn thế, họ lập thành những quốc gia phôi thai, từ đó mà tự xưng vương.

Trần Thái Tông (Trần Cảnh)

Vietnamese rendition of Trần Thái Tông (Trần Cảnh)

Tổ tiên của Trần Cảnh là một người tên là Trần Kinh (陈京), một người Phúc Kiến (闽人) sống vào thời nhà Tống - mặc dù cùng một nguồn cũng gợi ý rằng Trần Kinh có thể đến từ Quế Lâm thay thế, đó là lý do tại sao tôi nói rằng "có thể" Trần là người Phúc Kiến / Mân Việt.

Trần Kinh được cho là đã chuyển đến "Moxiang" (墨乡), ngày nay là tỉnh Nam Định ở miền Bắc Việt Nam, nơi ông và gia tộc của mình bắt cá để kiếm sống.

Trần Cảnh’s ancestor was someone by the name of Trần Kình (陈京), a Fujianese (闽人) who lived sometime during the Song Dynasty — though the same source also suggests that Trần Kinh may have come from Guilin instead, which is why I say it’s “likely” that Trần was Fujianese / Min Yue.

Trần Kinh is said to have moved to “Moxiang” (墨乡), in present-day Nam Định Province in northern Vietnam, where he and his clan took up fishing for a living.

Giang Nam/Jiangnam

Yue/Việt tộc rất giỏi đi thuyền, họ đã thoát Hán nhờ trận chiến trên sông và biển

Nước Việt 闽南

|

Sông Lạc cũng là nơi vua Đại Vũ nhà Hạ đã gặp rùa và nhận “Lạc thư” chỉ giáo về cách cai trị thiên hạ. Vua Đại Vũ là người Cối Kê - nay gọi là Kế Châu, tỉnh Giang Tô, thuộc vùng hạ lưu sông Dương Tử.[3] mà vùng này trong thời kỳ ấy đang còn là đất của các tộc Bách Việt.

Chú thích/Endnotes [1]Hán tộc là giống lai giống giữa hai nhánh chủng tộc du mục gốc Thổ (Turk) và Mông Cổ (Monolia). Trên 3000 năm trước) không có nước Tàu. Chỉ sau thời Ðông Chu Liệt quốc, Tần Thủy Hoàng thôn tính xong sáu nước cuối cùng, nên mới có nước Tàu.

[2]Thần Nông sống cách đây khoảng 5.000 năm và là người đã dạy dân nghề làm ruộng, chế ra cày bừa và là người đầu tiên đã làm lễ Tịch Điền (còn gọi là lễ Thượng Điền, tổ chức sau khi gặt hái, thu hoạch mùa màng) hoặc Hạ Điền - lễ tổ chức trước khi gieo trồng.

[3]Kế Châu, tỉnh Giang Tô, thuộc vùng hạ lưu sông Dương Tử. Giang Tô (江苏) là một tỉnh ven biển ở phía đông.

[4]

Vua Đại Vũ nhà Hạ là Tự Văn Mệnh (姒文命), ông là cháu 5 đời của Hiên Viên Hoàng Đế; cha Vũ là Cổn di chuyển người dân về phía đông Trung Nguyên. Vua Nghiêu phong cho Cổn làm người đứng đầu ở địa điểm thường được xác định là gần núi Tung Sơn.

[5]Nông nghiệp Bách Việt có khắc trên

Trống Đồng Ngọc Lũ.

|

| Đời | Xưng hiệu | Danh tính | Số năm tại vị | Thời gian tại vị | Xuất thân | Tài liệu |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Việt hầu Vô Dư (越侯無餘) | Vô Dư (無餘) | Con thứ của vua Hạ Thiếu Khang | Sử ký-Việt thế gia | ||

| 10 đời vua không rõ | ||||||

| 11 | Việt hầu Vô Nhâm (越侯無壬) | Vô Nhâm (無壬) | Ngô Việt Xuân Thu | |||

| 12 | Việt hầu Vô Thẩm (越侯無瞫) | Vô Thẩm (無瞫) | Ngô Việt Xuân Thu | |||

| 20 đời vua không rõ | ||||||

| 33 | Việt hầu Phu Đàm (越侯夫譚) | Phu Đàm (夫譚) | 27 | 565 TCN - 538 TCN | Sử ký-Việt thế gia | |

| 34 | Việt hầu Doãn Thường (越侯允常) | Doãn Thường (允常) | 42 | 538 TCN - 496 TCN | Con trai Phu Đàm, xưng vương năm 510 TCN | Sử ký-Việt thế gia |

| 35 | Việt vương Câu Tiễn (越王句踐) | Câu Tiễn (句踐) biệt danh Cưu Tiên (鳩淺) |

33 | 496 TCN - 464 TCN | Con trai Doãn Thường | Sử ký-Việt thế gia Chiến Quốc sử |

| 36 | Việt vương Lộc Dĩnh (越王鹿郢) | Dữ Di (與夷) cũng có tên Lộc Dĩnh (鹿郢) cũng gọi là Ư Tứ (於賜) |

6 | 463 TCN - 458 TCN | Con trai Câu Tiễn | Sử ký-Việt thế gia Chiến Quốc sử |

| 37 | Việt vương Bất Thọ (越王不壽) | Bất Thọ (不壽) | 10 | 457 TCN - 448 TCN | Con trai Lộc Dĩnh | Sử ký-Việt thế gia Chiến Quốc sử |

| 38 | Việt vương Chu Câu (越王朱句) | Ông (翁) biệt danh Châu Câu (州句) hoặc ghi Chu Câu (朱句) |

37 | 447 TCN - 411 TCN | Con trai Bất Thọ | Sử ký-Việt thế gia Chiến Quốc sử |

| 39 | Việt vương Ế (越王翳) | Ế (翳) cũng có tên Thụ (授) cũng Bất Quang (不光) |

36 | 410 TCN - 375 TCN | Con trai Chu Câu | Sử ký-Việt thế gia Chiến Quốc sử |

| 40 | Việt vương Thác Chi (越王錯枝) | Thác Chi (錯枝), cũng Sưu (搜) | 2 | 374 TCN - 373 TCN | cháu nội của Việt vương Ế, con trai của Chư Cữu (諸咎) | Sử ký-Việt thế gia Chiến Quốc sử |

| 41 | Việt vương Vô Dư (越王無余) | Vô Dư (無余) Mãng An (莽安) cũng Chi Hầu (之侯) |

12 | 372 TCN - 361 TCN | Thuộc gia tộc của Việt vương Thác Chi | Sử ký-Việt thế gia Chiến Quốc sử |

| 42 | Việt vương Vô Chuyên (越王無顓) | Vô Chuyên (無顓) "Kỉ biên" viết Thảm Trục Mão (菼蠋卯) |

18 | 360 TCN - 343 TCN | Sử ký-Việt thế gia Chiến Quốc sử | |

| 43 | Việt vương Vô Cương (越王無彊) | Vô Cương (無彊) | 37 | 342 TCN - 306 TCN | "Sử ký tác ẩn" nói là em trai của Vô Chuyên | Sử ký-Việt thế gia Chiến Quốc sử |

| Năm 306 TCN, Sở đánh bại Việt, Việt vương Vô Cương bị sát hại. | ||||||

Hán tộc là nhánh chủng tộc du mục có gốc Thổ (Turk/Persian), Hung Nô và Mông Cổ (Mongolia),

Hán tộc là nhánh chủng tộc du mục có gốc Thổ (Turk/Persian), Hung Nô và Mông Cổ (Mongolia), Những vua Vũ nhà Hạ, cả Phục Hy, Thần Nông, Nữ Oa, Đế Nghiêu, Đế Thuấn…

Những vua Vũ nhà Hạ, cả Phục Hy, Thần Nông, Nữ Oa, Đế Nghiêu, Đế Thuấn…

No comments:

Post a Comment